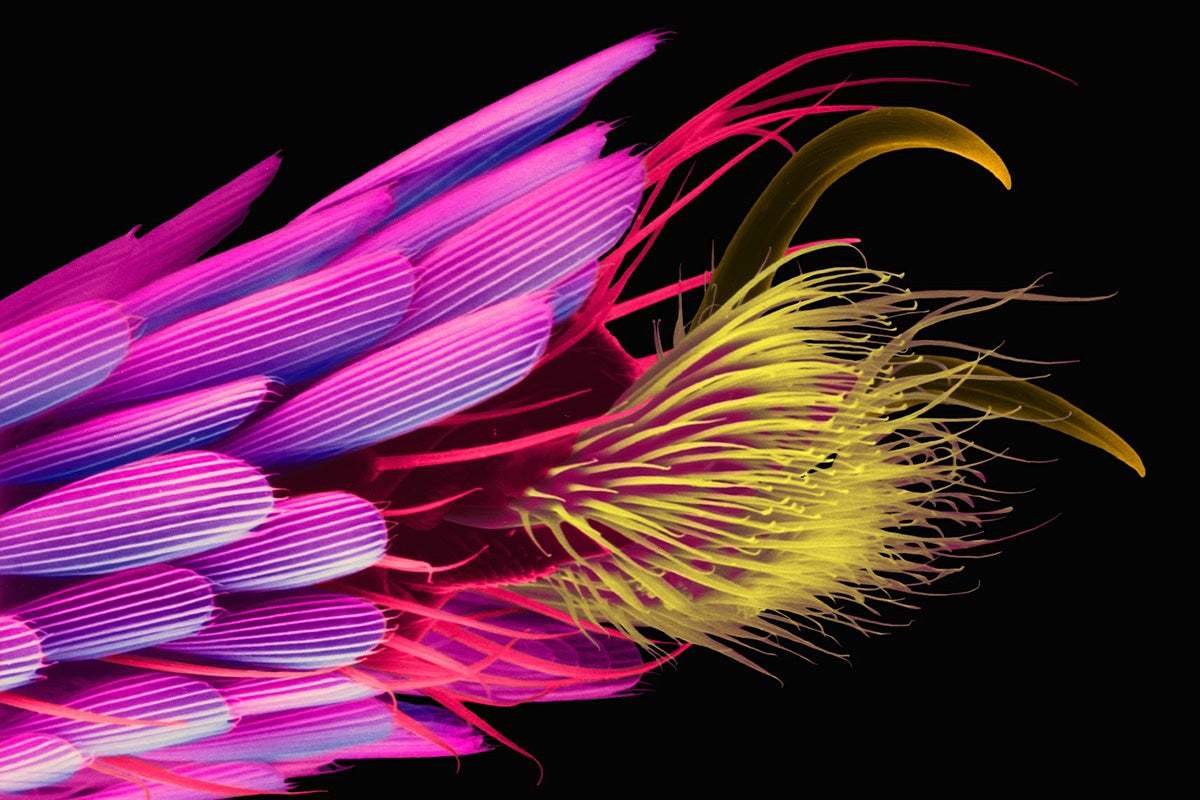

A known and prevalent disease vector, the Aedes aegypti is responsible for near-annual outbreaks of infectious diseases like dengue and chikungunya as well as thousands of annual deaths in Brazil alone.(Photo/David Scharf)

The Bite Stuff

USC anthropologist Luisa Reis-Castro finds that researchers of one of Brazil’s deadliest mosquitoes have a lot to teach the world about how to fight disease.

On Wednesday, Feb. 3, 2016, months before the world descended upon her nation for the Olympic Games, Brazil’s then-President Dilma Rousseff made a televised address to a country on the verge of panic.

Politely though urgently, she asked the nation’s 207 million people for permission to enter their homes and issued a 747-word national television address about an “urgent fight … that must unite us all.”

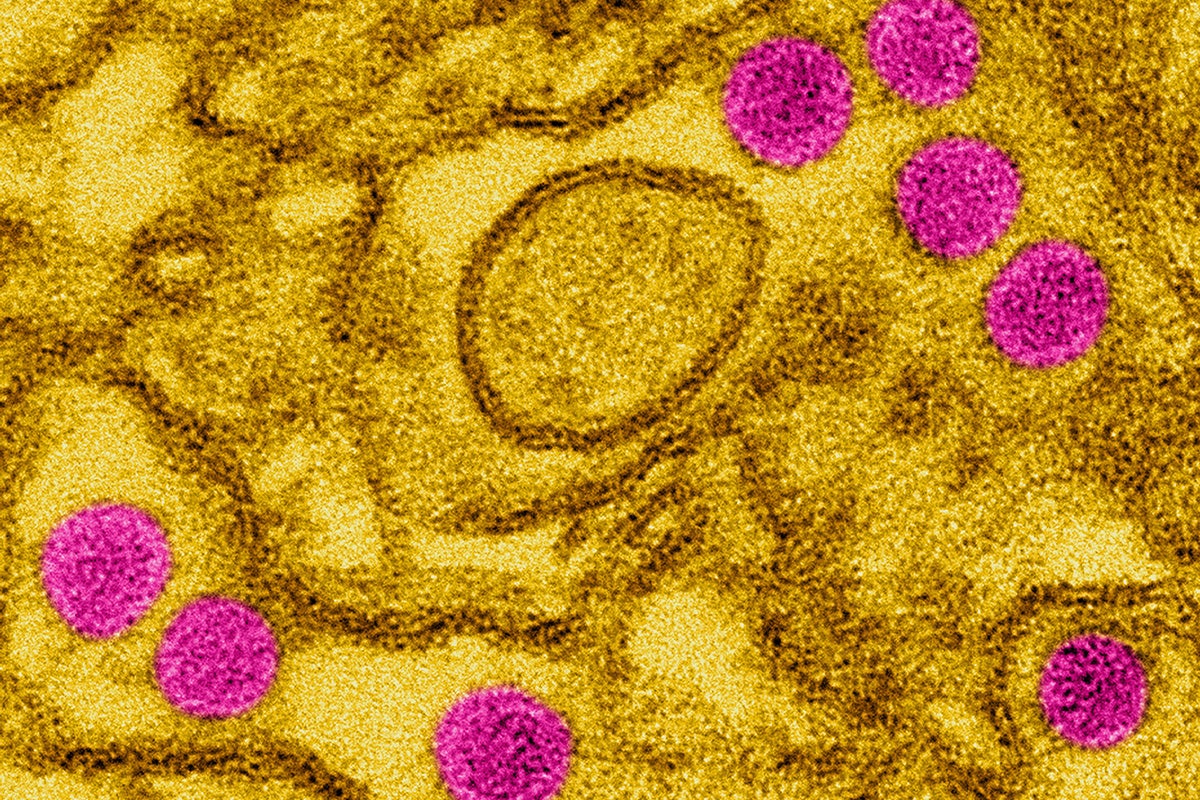

Rousseff warned not of war or bioterrorism, but of a tiny mosquito species — the Aedes aegypti, to be exact. The Aedes aegypti, Rousseff cautioned, transmitted the Zika virus and posed a particular threat to pregnant women by increasing the risk of microcephaly, a condition that causes babies to be born with small heads and underdeveloped brains.

Rousseff’s words carried concern for the well-being of the nation’s residents, particularly its soon-to-be mothers. She promised federal investment in the financial, technological and human resources necessary to combat the mosquito. Above all, though, she implored vigilance, urging “constant care” in homes, workplaces, schools and public places to eliminate the standing water that creates breeding sites and ignites the risk of Zika infection.

“Since science has not yet developed a vaccine against the Zika virus, the only truly effective medicine we have to prevent this disease is a vigorous fight against the mosquito,” she said.

Rousseff’s words underscored a burgeoning issue in Brazil and remain a significant marker in the country’s ongoing fight against the Aedes aegypti. A known and prevalent disease vector, the mosquito is responsible for near-annual outbreaks of infectious diseases like dengue and chikungunya as well as thousands of annual deaths in Brazil alone.

The Aedes aegypti isn’t a stranger to Brazilians. We know it’s a real threat.

— Luísa Reis-Castro

“The Aedes aegypti isn’t a stranger to Brazilians. We know it’s a real threat,” confirms USC-based anthropologist Luísa Reis-Castro, who grew up in Brazil.

To that point, the Brazil Ministry of Health launched a national campaign last October to battle the Aedes aegypti, which some health experts have labeled the nation’s top public health enemy. Television, radio, internet and outdoor media broadcast the campaign’s theme, “Every day is the day to fight the mosquito.”

Amid this ever-present concern, scientists across Brazil are pursuing novel research projects and innovative strategies to limit the Aedes aegypti’s propensity for damage. Their work holds implications for a swelling global population living with the species, including those in the United States.

For nearly a decade, Reis-Castro has been tracking scientific pursuits reconsidering how humans live with mosquitoes and offering unique ways to decrease the spread of infectious diseases. At the same time, Reis-Castro is also demonstrating how the Global South — often regarded as a place of disease — can instead be a source of groundbreaking solutions and new approaches to public health.

Tiny Yet Deadly

For more than a century, scientists in Brazil and around the globe have known the Aedes aegypti as an efficient vector for pathogenic viruses such as yellow fever and dengue. The mosquito’s bite can generate more than an irritating itch; it can be lethal.

The overwhelming intervention to combat the Aedes aegypti has been extermination, a move best characterized by the wide-ranging use of pesticides like DDT. The Aedes aegypti, however, has defied every effort of eradication and, in fact, become resistant to insecticides.

In addition, climate change has been a boon for the Aedes aegypti, an uber-resilient species that relishes warm weather. Climate change, globalization and the Aedes aegypti’s breeding capabilities have allowed the species to spread geographically. It has successfully migrated into the southern half of the United States, including Southern California.

“The question of how we will live with the Aedes aegypti is a critical one, especially given the severity of the diseases it transmits and its growing presence around the world,” Reis-Castro says. “The importance of finding different ways to address this problem is paramount and pressing.”

As international calls for interventions intensify, Brazil has emerged as the global epicenter of some of the most innovative science attacking the Aedes aegypti given its unique familiarity with the species.

“The problems Brazil is facing right now are problems the U.S. and others will soon face,” Reis-Castro says.

Seeing the Enemy as an Ally

Reis-Castro began her master’s degree work a decade ago, around the same time transgenic, or genetically modified, mosquitoes emerged as an alternative to insecticides and unlocked new approaches to addressing the species’ role as a disease vector. Transgenic mosquitoes represented inventive efforts to reduce the number of specific mosquito species like Aedes aegypti, which included a self-limiting gene preventing female mosquitoes — the ones that bite — from surviving to adulthood.

Learning about transgenic mosquitoes, Reis-Castro became intrigued by the experiments, particularly as she noted a corresponding rise in mosquito science projects exploring alternatives to eradication. A growing body of literature in anthropology discussing how nonhumans shape human lives only further intensified her interest.

We try to push it away, but it keeps coming back.

— Luísa Reis-Castro

“This mosquito insists on living with us, but we don’t want that,” Reis-Castro says. “We try to push it away, but it keeps coming back.”

In 2017, Reis-Castro began tracking Brazilian scientists, technicians and health workers and examining alternative strategies to combat the Aedes aegypti and its potential danger to humans. Specifically, she became interested in three efforts to harness the mosquito and use it to address the same pathogens it transmits.

In Rio de Janeiro, a group infected the Aedes aegypti with a bacterium called Wolbachia, a microbe that can inhibit viral transmission. In Recife, a group sterilized male mosquitoes through irradiation, releasing these insects to mate with wild ones on the island of Fernando de Noronha and prevent future Aedes aegypti generations.

A third group, in the southern Brazilian city of Foz do Iguaçu, made use of mosquitoes’ need for blood to mature eggs and their preference for biting humans to entrap the insects. The captured mosquitoes were then transformed into “sentinels,” mapping the insect’s presence, distribution and status as a vector.

A departure from the previous century’s extermination attempts, these three projects reimagined human interaction with the Aedes aegypti and stirred Reis-Castro’s fascination.

“Rather than trying to exterminate these vectors, these scientists are looking at how we might live with them and interact with them in a different way,” she says.

Rethinking Life with the Aedes aegypti

Reis-Castro is not evaluating the efficacy of the distinct scientific approaches, nor does she advocate for any one prospective remedy over another. Her work, however, represents a rare anthropological perspective on mosquito research. In showcasing Brazilian techniques that allow the species to populate, yet diminish their capacity to serve as vectors, Reis-Castro is identifying approaches that allow the Aedes aegypti to live while transforming their ability to harm humans.

“Because of climate change, the range of these vectors is expanding, and we all need to find ways to live with them,” says Andrew Lakoff, professor of sociology and anthropology at the USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences. “Luísa is opening our eyes to these possibilities by studying how cutting-edge science is approaching this disease vector.”

Indeed, Reis-Castro’s efforts, most recently conducted as a USC Society of Fellows in the Humanities researcher, are re-envisioning how humans relate to nature, helping to redefine ecological thinking and earning scholarly attention. Her 2021 paper in Environmental Humanities titled “Becoming Without: Making Transgenic Mosquitoes and Disease Control in Brazil” captured acclaim, including awards from the American Anthropological Association, the American Sociological Association and the Latin American Studies Association.

Reis-Castro notes that extermination was the prevailing strategy for fighting Aedes aegypti for more than 100 years — and it always failed. In acknowledging those failures and spotlighting the efforts of these Brazilian scientists, Reis-Castro tackles longstanding public health traps that couldn’t control outbreaks and notes compelling alternatives that can inspire science and propel solutions.

“She’s making the case for a shift in how we think about the relations between humans and disease vectors,” says Lakoff, one of Reis-Castro’s mentors during her postdoctoral research at USC. “Her work shows that what is happening in Brazil is likely to become relevant elsewhere in the world, especially as these vectors expand their presence.”

Championing Equity in Science

But Reis-Castro is doing more than highlighting compelling interventions for a dangerous public health enemy. She’s also challenging the way the story of global science is told.

The Global South, she says, has long been viewed as a place of disease and the source of problems like Zika, chikungunya and dengue. Reis-Castro aims to turn that tired tale on its head by demonstrating how Brazilian scientists and ecologies are producing original, pioneering science and crafting inventive solutions. With the constant threat of Aedes aegypti in Brazil, the country is forced to innovate in a way other nations, including the United States, are not — and such innovation, she contends, should not be ignored or minimized.

Brazil and the Global South can and should be thought of as a place where solutions are developed.

— Luísa Reis-Castro

“Brazil and the Global South can and should be thought of as a place where solutions are invented and developed,” says Reis-Castro, who will join USC’s faculty ranks this fall as an assistant professor of anthropology at USC Dornsife.

Beyond her interest in how Brazilian science can contribute to public health conversations on a global scale, Reis-Castro is also confronting the notion of equity in Brazilian science. Brazil, she notes, suffers from issues of racial and regional inequality, which affects scientific activity in the country.

During the presidencies of Michel Temer (2016-18) and Jair Bolsonaro (2019-22), drastic budget cuts in science and the public health system complicated health practices research. The remaining federal funding was often dispersed according to historical racial, gender, class and regional inequalities in a country accustomed to privileging some over others. Reis-Castro discusses this inequity in her in-development book, The World Will Become Brazil: Epidemics, Ecologies, and the Reinvention of Mosquito Science.

“Contemporary science and technology are producing fabulous things, but in pursuing innovation, it’s important to look at who benefits and who doesn’t,” says Peter Redfield, professor of anthropology at USC Dornsife and the Erburu Chair in Ethics, Globalization and Development at USC. “Luísa’s work speaks to that with specificity and depth of engagement.”

Reis-Castro hopes to see increased awareness of bias in Brazilian science and more earnest thought regarding who produces knowledge, whose information is valuable and how those two elements shape scientific funding. She says these are all important considerations in public health research, particularly with a problem as serious as the Aedes aegypti and its role as a vector of harmful diseases.

“Science can be a way to transform the world, but we need to be mindful of who gets to do the science,” she says.