(Illustration/Hanna Barczyk)

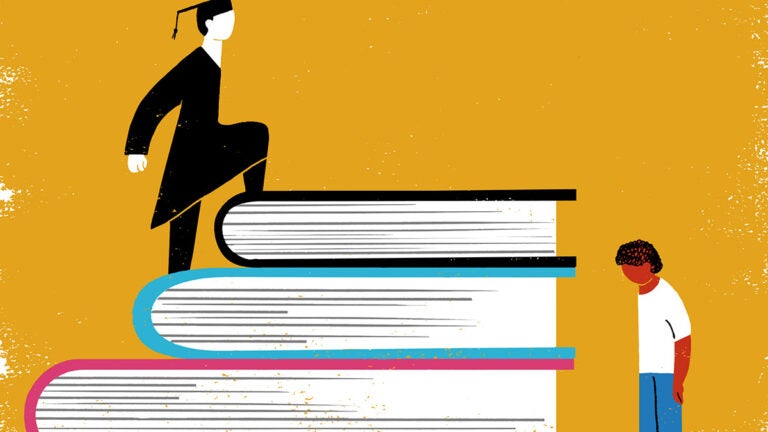

Educators Need to Break the Academic Bias Against Young Men of Color

Studies show that teachers and counselors often hold low expectations of boys from minority communities.

Almost 30 years ago, I sat in a middle school science classroom passively listening to a teacher discuss a new magnet high school.

Something about the excitement in the teacher’s voice as they talked about the culture of high expectations, academic opportunities, low student-to-teacher ratios and more resources to prepare for a career after high school graduation resonated with me. As I reached for the paper brochure, my science teacher quickly and quietly told me, “That school isn’t for kids like you — kids who aren’t serious about their education.”

I haven’t thought about that teacher in more than 20 years. But I still remember that feeling of anger and confusion about why a “kid like me” couldn’t attend a specialized magnet school with unique opportunities and resources to help urban kids graduate from high school. As a tenure-track faculty member in the Pullias Center for Higher Education at the USC Rossier School of Education, I understand now what happens when urban schools gradually lower the expectations and excitement of boys and men of color as they aim to succeed through the educational pipeline. Federal education data tell us that only around 50% of boys who identify as Black, Latino, Southeast Asian, Pacific Islander or Native American will graduate from U.S. high schools.

The low high school graduation rate for boys of color is due not to a lack of academic talent.

The low high school graduation rate for boys of color is due not to a lack of academic talent but rather to hiccups in equal educational opportunities. Schools that enroll large portions of boys of color are often underfunded compared to peer schools in the same district. This creates an unfair or unlevel playing field. There is also a perfect storm of insufficient and unequitable school funding matched with lowered expectations from some educators who may believe that boys of color and their families aren’t invested in education.

Boys of color face society’s low expectations

The research I have conducted over the last 10 years paints a different picture. Boys of color want to earn a college degree, become “somebody” in their community with a stable and well-paying career, and be role models to younger siblings and family members by showcasing that a college education is achievable. However, in other research that I have conducted, some high school teachers and counselors intentionally withhold college information from kids — primarily boys of color — believing these students aren’t serious about education.

Due to my own challenging and negative experiences in middle and high school, I am now working with two of the largest college access and school counseling organizations in the U.S. We’re working on how to best support high school counselors to adjust their school-based practices and promote higher education for boys of color instead of guiding them away from economic opportunities. Research from the College Board tells us that pursuing higher learning — including associate, bachelor’s or graduate degrees and certificates and credentials — provides the skills and professional networks that almost guarantee more upward social mobility compared to stopping at high school.

When only half of all boys of color graduate from high school, their numbers narrow at the college level: National data tell us that only 1 in 5 men of color hold a bachelor’s degree. To address this issue at the college level, I lead the Pullias Center of Higher Education’s men of color team, working with California State University campuses to revise policies and practices to promote retention and degree completion among these men.

Earning a college degree is a team sport: All students need help and guidance.

Earning a college degree is a team sport: All students need help and guidance. Faculty members and academic advisors can serve as mentors to show men of color the path toward degree completion. In our training with the California State University system, we had tough, thoughtful and action-oriented training that set a foundation for staff, faculty and administrators to build a support system to help men of color graduate.

These days, as I think about my middle school science teacher, I’m glad that I didn’t listen to her. Still, her unenthusiastic message could have resonated with another student who may have opted out of higher education altogether. We have to fix that.