Isaac Vigilla, left, talks with Uluwehi Baldemor, center and LooLoo Amante, right, during the inaugural USC Native American & Pacific Islander Student Association cultural festival. (USC Photo/Gus Ruelas)

For Pacific Islanders at USC, PISA provides friendship and family

The student organization, formed in the fall, offers support for students facing cultural barriers and other challenges as they navigate university life

[new_royalslider id=”181″]

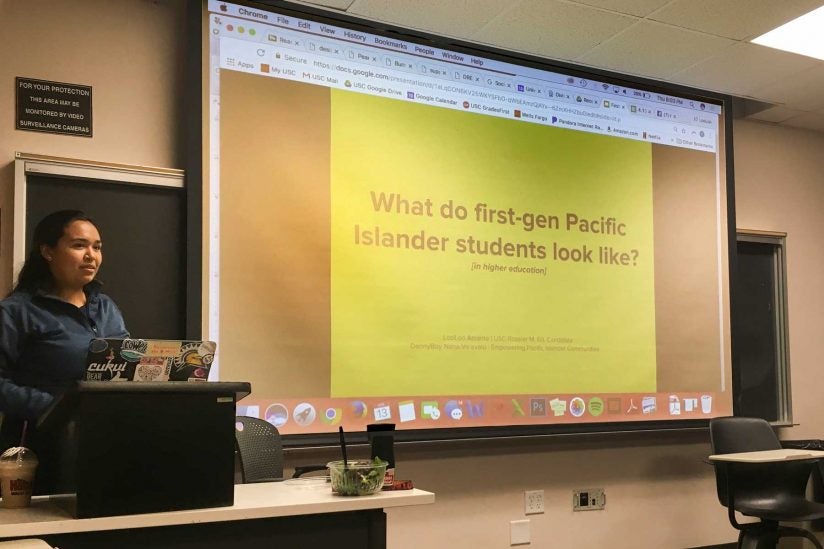

LooLoo Amante is in a classroom in USC’s Von KleinSmid Center.

She got there early so she could push the desks around, pulling some out to form a semicircle, and lay out snacks she bought, chips and pretzels.

She grabs some chalk and writes Talofa Lava on the blackboard. It’s a greeting in Samoan.

Then she waits.

“Hopefully people aren’t living on island time today,” she said with a laugh.

It’s Thursday and nearing 7:30 p.m. She’s waiting for the rest of PISA, the Pacific Islander Student Association. Started in the fall, it’s USC’s first student organization focused solely on the Pacific Islander community. Amante spearheaded it.

“It’s a long time coming,” Jonathan Wang, manager of USC’s Asian Pacific American Student Services (APASS), said of PISA.

Nationally, the group is underrepresented in higher education. Among Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander adults in California over the age of 25, about 14 percent have a bachelor’s degree and 5 percent have a graduate or professional degree, according to U.S. Census Bureau five-year estimates from 2006-2010. (Among California’s overall population over 25, about 19 percent have a bachelor’s and 11 percent have a graduate or professional degree.)

Pacific Islanders are a small group at USC. In fall 2016, there were 30 undergraduates and 65 graduate students who identify as Pacific Islander, according to APASS.

About 45 of them joined PISA.

PISA gives Pacific Islander students a sense of community at school but also encouragement that they might not get from their own families.

It’s unclear how many at USC are the first in their families to attend college, but Amante said it’s very common given the statistics in the community. Amante — who is Samoan, Filipino and Mexican — is the first in her family to finish elementary school, middle school, high school and graduate from college. She has a bachelor’s degree from San Jose State University and just completed her first year in a USC Rossier School of Education master’s program in postsecondary administration and student affairs. When she graduates, she wants to work with her community — either in student affairs, admissions or research.

Growing up in and out of poverty, she said, “I’ve always been determined education is going to be my outlet.”

Cultural gaps are among the barriers that hinder Pacific Islanders from completing degree programs, Amante said. For one, there are only limited highly educated role models — college professors, doctors or attorneys — with Pacific Islander backgrounds, she said.

“Truly, some of our students are trailblazers,” Wang said. “They might not know anybody with these degrees or in these fields.”

Conflicting cultural values

Because of conflicting cultural values, Amante said, there’s less of an expectation to attend college. What’s more culturally ingrained is providing for your family early on. It’s common for Pacific Islanders to financially support their families as early on as high school. It can be seen as selfish to take four years — or more if you attend graduate school.

Amante knows this. She helped pay her mom’s rent while she was in college at San Jose State, never letting her know that she was struggling herself. For a while, she was on food stamps and homeless — couch-hopping with friends or sleeping in her car while juggling jobs, running cross-country, studying and being student body president.

“That’s one of my hardest stories to talk about,” she said. “I don’t tell people I was homeless.”

The summer before she started at USC, unbeknownst to friends, she was back in her car. In the fall, she ended up getting a job as a residential adviser for football players, giving her a place to live. She also works two jobs, as a barista at Philz Coffee and in the USC Athletics Department as an academic learning specialist.

For some students, a lack of resources and support combined with the pressure to provide for the families can cause them to lose the will to finish.

“Since education wasn’t rooted in them in the beginning, it’s hard to root it in the future,” said Sarahfina Luuga, a PISA member and master’s candidate in social work and public health. “When we have kids in the future, we can share the wisdom with them that, you know, an education is important. … I’m really thankful to have supportive parents who pushed me.”

In Samoan, there’s the phrase Fa’a Samoa, which means the Samoan way. To Amante, it means family first.

Family and togetherness

PISA embodies the Polynesian focus on family and togetherness in many ways. Members call each other cousins, even though many met just months ago. And there’s the way they call each other up on the phone about family dinners: If you can’t go, they want to know why, Luuga said.

“Every time I go to meetings, I feel like I am at home,” said Luuga, 23.

Amante makes a point to wear something tied to her heritage all the time, like earrings from American Samoa.

“I want them to feel like they have a sense of identity when they see me,” Amante said.

Only seven or so show up to the meeting, but that’s expected with finals ahead. They discuss end-of-the-year things — the first cultural festival, held jointly with the Native American Student Union, and PISA sashes for graduates.

Amante dims the lights for a quick presentation. When it comes to their community, Amante is encyclopedic. She shares a map of U.S. rights and benefits of islanders across the Pacific, facts about colonization, the white appropriation of the luau and stereotyping.

“Most people think about football players,” she said about Pacific Islanders in higher education. “We want to kind of unravel and unpack it because this is the front face of Pacific Islanders and Polynesians in higher education.”

Even though it’s about 9 p.m. and they still have studying to do, she has a captive audience. They pop in with remarks – talk about the Mormon conversion of Tongans and the growing Pacific Islander community in Las Vegas.

Talking about these things is important to Amante and many in the community because when it comes to research and academics, they feel their community is “rendered invisible” — often lumped in with Asian Pacific Islanders, an umbrella term for about a dozen ethnicities, according to the organization Empowering Pacific Islander Communities.

The meeting lasts longer than expected, but Amante asks everyone just to stay for five extra minutes for an activity.

She asks them to write down something they are proud of, a highlight and a wish.

They go around and share.

“My highlight is definitely PISA,” the group’s secretary, Tanya Sapa, said.

When it makes it back to Amante, she’s emotional.

‘Growing and graduating’

“My wish is for PISA to continue,” she said. “Our people are growing and graduating. Who will fill our seats? That’s my fear. How are we going to survive?”

Tears roll down her face.

“School is hard. Sometimes I want to drop out,” she said. “I think about PISA and I’m like — I can’t leave you guys.”

They console her. One member chimes in and says how excited she was when she got her first email about PISA. Sapa says she can’t believe PISA was just “a thought” the past summer.

Amante worries about others carrying on the torch, but she won’t be alone — because at USC, she created a family.