A woman sees religious phenomena that others cannot

Photos and analysis from two USC scholars explore a contemporary visionary ritual devoted to the Virgin Mary in California’s Mojave Desert

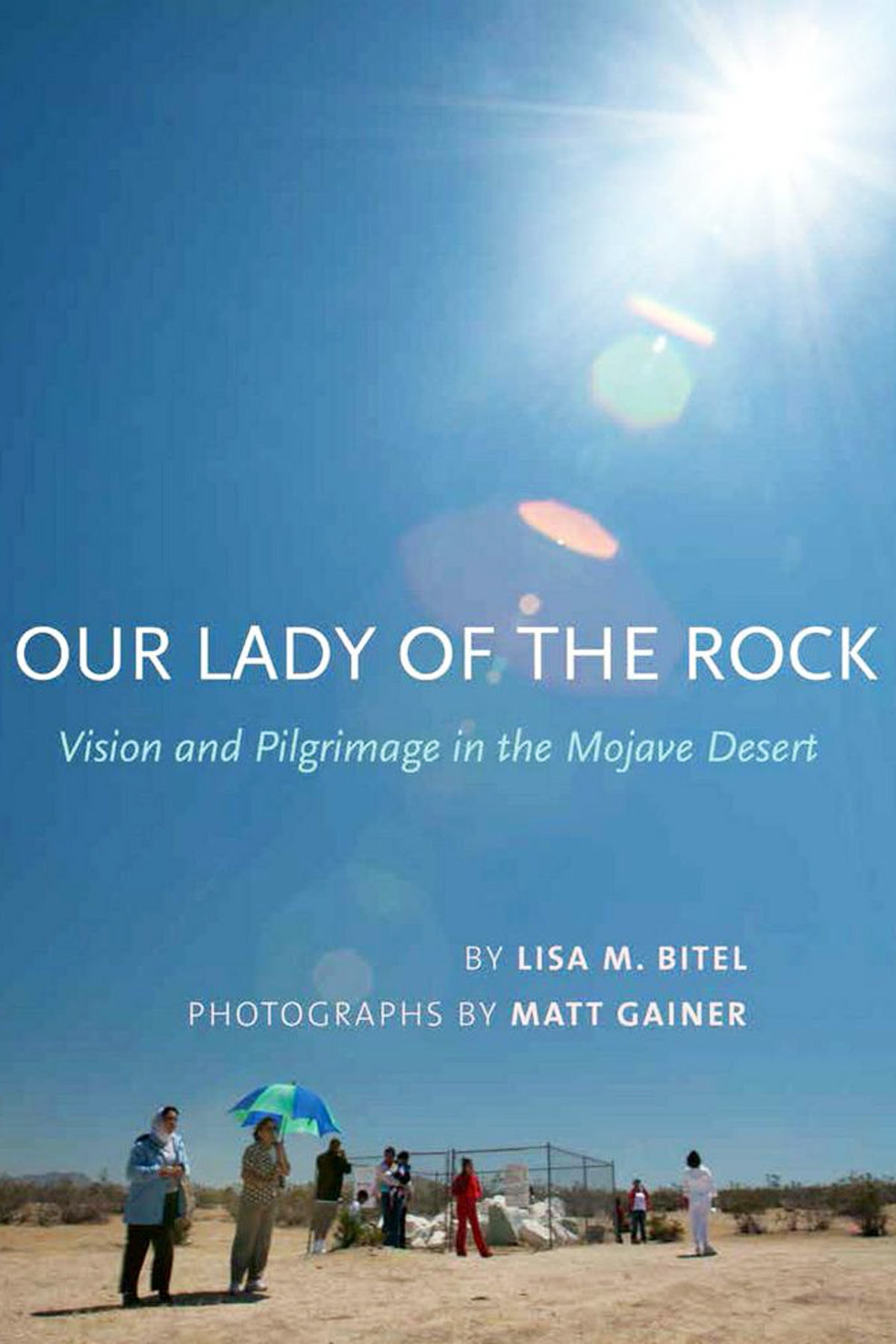

Standing amid the desolate beauty of the California desert, hundreds of people raise instamatic cameras to snap pictures of a cloudless, cerulean sky. Others drop to their knees beside their cars and pick-up trucks, yet more hold their infants and children up to the sky as if to be blessed.

The date is the 13th, and this month, like every other, hundreds of ordinary men, women and children have been transformed into modern pilgrims as they gather at this remote spot in the Mojave Desert north of Los Angeles.

These people have followed a self-proclaimed visionary, Maria Paula Acuña, out into the desert to watch her see what they cannot — the Virgin Mary, whom Acuña claims appears in the sky here at 10:30 a.m. on the 13th of each month.

Our Lady of the Rock

While Acuña sees and speaks with the Virgin at this place known as Our Lady of the Rock outside California City, onlookers scan the horizon for signs from heaven, snapping photographs of the sun and sky. Not all are convinced she can see the Virgin, yet at each vision event, they watch for subtle clues to Mary’s presence, such as the unexpected scent of roses or a cloud in the shape of an angel.

The visionary depends on her audience to witness and authenticate her revelations while observers rely on Acuña and the Virgin to create a sacred space and moment where they, too, can experience direct contact with the divine.

The culmination of six years of observing this phenomenon and interviewing and photographing those involved, Our Lady of the Rock: Vision and Pilgrimage in the Mojave Desert (Cornell University Press, 2015) combines more than 60 evocative photos by Matt Gainer MFA ’97, director of the USC Digital Library, with textual analysis by Lisa Bitel, professor of history and religion at the USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences.

Examining the rituals, iconographies and physical environment of Our Lady of the Rock, the book provides vivid portraits of the pilgrims. It also documents the responses from the Catholic Church and popular news media regarding Acuña and other contemporary visionaries.

In 2006, Bitel, a specialist in the supernatural in early medieval Europe, first learned of Acuña after reading a 1997 Los Angeles Times article about a vision event in the Mojave Desert.

Questions about the past

“I am trained to approach history with an ethno-historical emphasis that encourages us to look at modern people and events and then apply those observations to questions about the past,” Bitel said. “This was an opportunity to see a religious vision in action.”

This was an opportunity to see a religious vision in action.

Lisa Bitel

Bitel and Gainer made dozens of trips out to the desert between 2006 and 2012 to document the vision events at Our Lady of the Rock. Initially, Gainer was intrigued by the idea of what people actually saw during a vision experience. But then he became fascinated by differences between his own documentary method of taking and viewing pictures and the way Acuña’s followers use photography to validate and interrogate ideas about what they were seeing and whether it is real.

“They used Polaroid cameras, pointing them at the sky or wherever Maria Paula said the Virgin was, and sometimes they would point them in other directions just to explore, to see what happened,” said Gainer, who is also a research associate at USC Dornsife’s Center for Religion & Civic Culture. “Then the community would share the photographs with each other, interpret them, trade them and paste them into scrapbooks.”

A lexicon of meaning

Over time, a lexicon of meaning developed around the aberrations or impressions left on the Polaroids, so one might be interpreted as the gates of heaven and another as an ascending angel.

There was a collective understanding about this iconography that fascinated me.

Matt Gainer

“There was a collective understanding about this iconography that fascinated me because the kind of pictures I take are tied to the world in all its mundane beauty — the world as it looks in front of the camera,” Gainer said.

“What they were making pictures of and seeing in the photographs relied on being open to additional layers of meaning. For example, I might explain an unusual impression in a photo as the result of over or underexposure, or flares occurring as a result of the camera lens, while a pilgrim might interpret it as an angel, or the Virgin herself.”

When Gainer was asked by a pilgrim what he saw, she remarked that he was “looking the wrong way.”

“At first I thought she meant I was looking in the wrong direction, but then I realized she was talking about ways of seeing, understanding and finding meaning.”

As a result, Gainer’s role as a photographer became not only about documenting the weekly rituals, but also about exploring how photographs themselves play an actual role in faith.

??Orthodox rituals

His photographs and Bitel’s text explain how Acuña and her followers have formed their own Catholic community focused on the Virgin Mary and the practice of revelation in which they re-create or imitate orthodox rituals.

“There’s a whole liturgy and a protocol that’s as formal as anything you’d see in a Catholic Church, but it’s outside the church,” Bitel said. “Maria Paula’s helpers dress in white habits like Catholic nuns and each month her followers participate in a procession with an icon of the Lady of the Rock, a statue of the Virgin Mary. They sing hymns and pray with rosaries.”

During the rituals, followers picnic and chat in a fiesta-like atmosphere that may also go some way toward explaining the events’ appeal.

Acuña’s followers, the majority of whom are Spanish speakers, include many with long-term or incurable disabilities who hope Acuña’s prayers and the Virgin’s presence may help them find cures.

“It’s a way of taking their religion and problems into their own hands,” Bitel said.

“Of course everyone asks, ‘Do you think she sees what she says she is seeing?’ ” Bitel said. “Frankly, I have no idea.

“How does someone who is a not a Catholic or a believer of some kind answer that question? How do we study people who have a completely different reality and set of perceptions than we do?” Bitel asked. “It’s the elephant in the classroom: the divine, the supernatural. The dilemma of Christian revelation is that you can never know what another person sees — so how can you analyze it?”

However, Bitel argues, that is not the scholarly observer’s most important task.

Leap of faith

“The most important question is how a group of people who want to believe come together and create a process by which they can agree on what they are seeing. I can take this leap of faith as a model. In a similar way, I look at evidence from the present day in order to understand something about the long history of people seeing religious phenomena that others cannot — the long history of spiritual looking.”

Acuña and her followers may sound unusual, but they’re not alone in their devotion to religious visions.

Bitel, who collects religious kitsch, including recent instances of Jesus appearing in a taco shell and Allah’s name on a fish, said modern-day visionaries like Acuña are contributing to a debate that has gone on for centuries and recently gained momentum among scholars of religion.

Bitel’s research has shown that visionaries and their followers are using social media outlets such as Twitter, YouTube and online discussion forums to share their experiences with each other and the online community.

“Practitioners of visionary religion seek the newest technological means to facilitate their religion,” Bitel said. “There’s a popular belief that people who would go out and look for the Virgin Mary don’t know how to use a computer or a cellphone, and that is absolutely not true.”

Bitel said she once thought visions were more frequent in the Middle Ages. Now she is not so sure.

“Visions are thriving online,” Bitel said. “With a little research, you can find one happening near you.”