What happens when ideas are put on trial?

In 1610, the Roman Catholic Inquisition condemned Italian scientist Galileo Galilei for promoting the heretical idea that the Earth orbited the sun. He was banned from writing or teaching on the subject ever again. Books and papers that promoted this “heliocentric” idea were burnt.

It was a powerful example of the way an oppressive Catholic Church stymied scientific discovery. Or, so the popular narrative goes.

Edwin McCann has been teaching the “Ideas on Trial” course since the 1980s. (Photo: Courtesy Edwin McCann.)

If you take Edwin McCann’s course “Ideas on Trial” (PHIL 284) at the USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences, you’ll learn there’s a bit more nuance to the story.

Galileo could have easily been burnt for heresy, says McCann, professor of philosophy and English, but the Catholic Church decided to find him guilty of a lesser crime and sentenced him to house arrest. Galileo spent the rest of his life in a comfortable villa, bills footed by the Vatican.

“Galileo was now completely financially supported by the church,” says McCann. “He didn’t have to support himself by taking on private students for instruction. So, he was able to complete his last great work, Discourses and Mathematical Demonstrations on Two New Sciences.

From surfing to Socrates

Humanity has been putting people on trial for their ideas or beliefs for thousands of years, and the outcomes have marked significant shifts in culture. They’ve also formed a sort of mythology, like the Galileo story, simplified and Hollywood-ized into narratives in which good triumphs over evil or progress is repressed by archaic institutions.

McCann’s class peels back the layers of obfuscation for students. Uncovering the nuances of these trials is one part of PHIL 284, along with understanding how these trials reveal cultural or philosophical divisions in society.

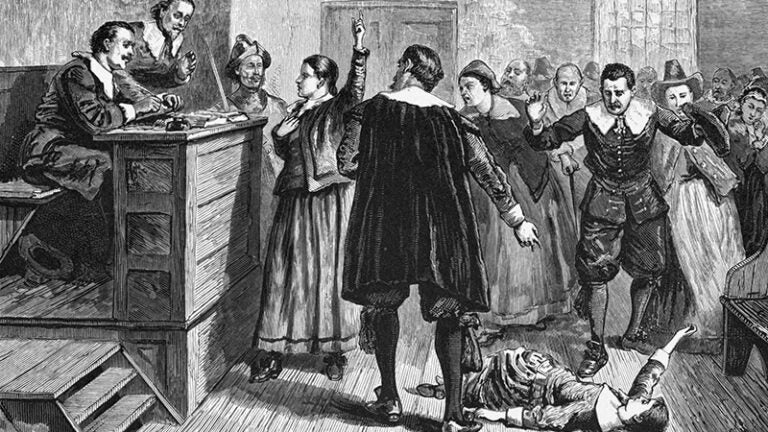

They touch on the trials of Socrates, Galileo and Scopes, which highlight the conflict between science and religious belief, the trial of Joan of Arc and the Salem Witch Trials, both intertwined with gender and the supernatural, and the war crimes trials of the 20th century, which consider what it is to be human in the age of advanced technology.

They are conflicts which rage on today. One trial on his syllabus, the 2005 Kitzmiller v. Dover Area School District, challenged a mandate in Pennsylvania to teach “intelligent design” alongside evolution, a mandate which generated the “flying spaghetti monster” meme.

The meme stemmed from a satirical letter published in response to the mandate, written by the activist Bobby Henderson, that demanded the state also teach his religion. He worshipped “the flying spaghetti monster” as part of “pastafarianism,” the letter declared, and schools should therefore include his religion in their lessons.

McCann started the course in the 1980s, alongside Jim Kincaid, Professor Emeritus of English and Aerol Arnold Professor Emeritus of English, and Christopher Stone of the USC Gould School of Law, and has been teaching it regularly ever since.

McCann’s own interest in philosophy began his freshman year of college, when he first read the Danish theologian and philosopher Soren Kierkegaard. Prior to that, he hadn’t exactly planned on an academic career.

Growing up in the San Fernando Valley, he’d been more interested in surfing than Socrates. “I’d surf point breaks. Rincon and California Street in the winter, and Malibu and Leo Carillo State Beach in the summer,” he says.

After his high school sweetheart Linda headed off to college, he thought he’d might as well enroll somewhere as well. San Fernando Valley State College (now California State University, Northridge) had enrollment space, but there were few classes with openings left. He selected one on world religions, where he had his fortuitous encounter with philosophy.

He joined Linda at the University of California, Santa Cruz for two years, then went on to get a PhD in philosophy from the University of Pennsylvania in 1975. He’s been with USC Dornsife since 1983. (And he and Linda recently celebrated 51 years of marriage.)

The trial of Galileo seemed to pit religion against science, but Edwin McCann says the truth is a bit more complicated. (Image Source: Wikimedia Commons.)

Hollywood license

Alongside the facts of the historic trials, the class also examines their dramatic depictions. McCann says many popular representations have imprinted inaccurate versions of events into the public’s mind, falsehoods which have persisted for decades.

Take the 1960 film Inherit the Wind, based on the 1925 Scopes “Monkey” Trial in which high school teacher John T. Scopes was tried for teaching evolution in the classroom in violation of Tennessee’s Butler Act, which forbade the material.

The first scene of the film depicts outraged locals barging into the classroom during a lesson when, in fact, Scopes likely never actually taught evolution. The whole case was mostly a set-up.

“The power brokers of Dayton, Tennessee, wanted to put the town on the map. They twisted Scopes’ arm to be the test case for Tennessee’s anti-evolution act, so they would get publicity for the town and turn it into a tourist destination,” says McCann.

Scopes’ lawyer Clarence Darrow, and others on his defense team, coached the students to give false testimony.

Of course, that doesn’t make for as compelling a film. Which is why the scene of the outraged parents and other details, including a fictious romance between Scopes and a local fire-and-brimstone preacher’s daughter, were added to the script.

“It’s a salutary lesson for people to see how the misconceptions that they may have been subjected to, along with practically everybody else, might actually present a false and distorted picture of that historical epic,” says McCann.

War crimes in real time

For students like Sophia Meyer, an Italian and law, history and culture major, the course has both informed her about the past and about our modern world. Halfway through the semester, Russia’s war in Ukraine began. It coincided with readings on the 1945 Nuremberg and 1961 Eichmann trials, in which German Nazis were tried for crimes against humanity.

The field of international criminal law, which defines and prosecutes severe crimes committed by nation states, was developed from these trials. While the class studied, Russia was accused of committing war crimes against Ukraine.

“Being in PHIL 284 has given me a vastly updated frame of reference when reading and talking about the conflict in the Ukraine,” says Meyer.

She’d enrolled in the class to broaden her mind, part of a process that began when she moved from the suburbs of New Jersey to the diverse sprawl of Los Angeles to attend USC Dornsife.

McCann’s three decades of teaching the complex subject has earned him rave reviews from students like Meyer.

“Anybody can become an expert in a topic and think they’re able to teach others about it, but it takes a special extra something else to truly thrive at it. I can’t describe exactly what that something is, but Professor McCann has it,” she says.