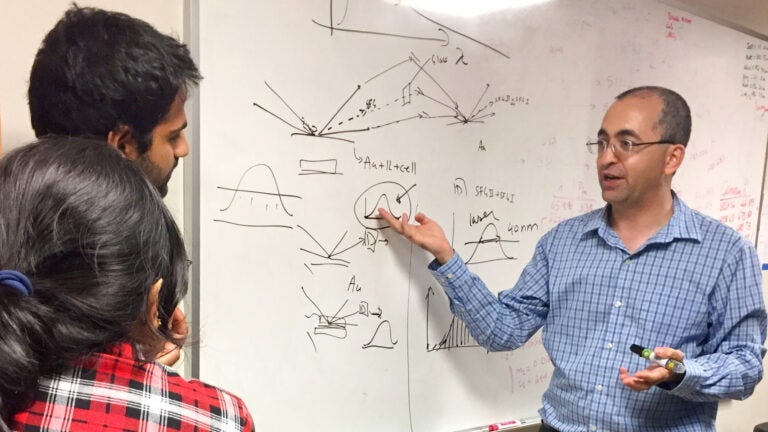

Associate Professor Jahan Dawlaty brings perspective gained from his early adulthood as a Afghan refugee to his mentorship of students. (USC Photo/Rhonda Hilbery)

From refugee to researcher, chemist Jahan Dawlaty is a catalyst in the lab and classroom

The scientist’s path to USC was paved with challenges, beginning with his childhood in Soviet-occupied Afghanistan

How do chemicals interact with an electrically active surface? Why does a particular chemical become more alkaline when exposed to light? The answers to these questions remain elusive — but that makes them all the more intriguing to Jahan Dawlaty.

Dawlaty, an associate professor of chemistry at the USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences, pokes into the marrow of chemistry problems in search of new or deeper understanding. But his road to academe was paved with challenges: He grew up in Kabul, Afghanistan, where a civil war erupted after the Soviet Union withdrew from a long occupation in 1989, just as he neared high school graduation.

“That’s when we left because it was getting really dangerous,” he said. “The people who had fought the Soviets for all those years were now fighting each other.”

Now refugees, the family of eight fled to Pakistan, where Dawlaty completed high school, but college opportunities in Pakistan for refugees were precarious at best.

After hearing about a friend of a friend who managed to get an education in the United States, he decided to try that route himself and attended Concordia College in Minnesota. After completing his undergraduate chemistry degree at Concordia, he earned his PhD at Cornell University. Dawlaty arrived at USC in 2012 after completing postdoctoral work in physical chemistry at the University of California, Berkeley.

Physical chemistry research in two areas

A physical chemist, Dawlaty focuses much of his research on two main areas. In one, he measures surface properties of electrochemical interfaces. For example, what happens when water is poured into a metal cup? Water molecules in the middle of the cup behave differently than the molecules that directly touch the cup’s surface. These differences affect the chemistry near the surface and are especially important in converting electrical energy to chemical energy, and vice versa as occurs in batteries.

Another research direction emerged after one of Dawlaty’s graduate students became interested in a molecule that seemed to become more basic after being subjected to light. That’s important, Dawlaty explained, since a sudden increase in basicity suggests that these molecules can be used to remove protons in certain catalytic reactions.

“At the time, we had no idea that anybody would step in any time soon to implement this property for an actual chemical reaction,” Dawlaty said. “Since then we have studied it in great detail and it became a nice fundamental science set of studies.” This research thread resulted in several publications and a collaboration with a USC chemistry colleague on incorporating the molecule in catalysts to accelerate chemical reactions.

Whenever accolades come his way, Dawlaty is quick to credit the contributions of the students he works with. Declaring that student enthusiasm and insight often leads to new research avenues in the realm of physical chemistry that he explores, he insisted, “I often learn as much from them as they do from me.”

Beyond research: mentoring physical chemistry students

Besides his research accomplishments, Dawlaty is known as a committed mentor who is generous with his time and attention to students. Chemistry PhD candidate Nicholas Orchanian said he was floundering as a junior before he took a physical chemistry course taught by Dawlaty five years ago.

Orchanian dreaded taking the required class, but his professor’s inspired teaching, mentorship and offer of undergraduate research opportunities changed his life. Now pursuing solar energy materials research in the lab of Assistant Professor Smaranda Marinescu, Orchanian calls his former teacher’s dedication to students “extraordinary.”

“Even now,” Orchanian said, “I continue to seek out Jahan’s guidance and am always greeted with an open door and a listening ear.”