Study: Doctors reduce opioid prescriptions after learning a patient overdoses

USC Schaeffer Center study shows that when clinicians are given information about a patient’s overdose, they prescribe fewer of the powerful painkillers

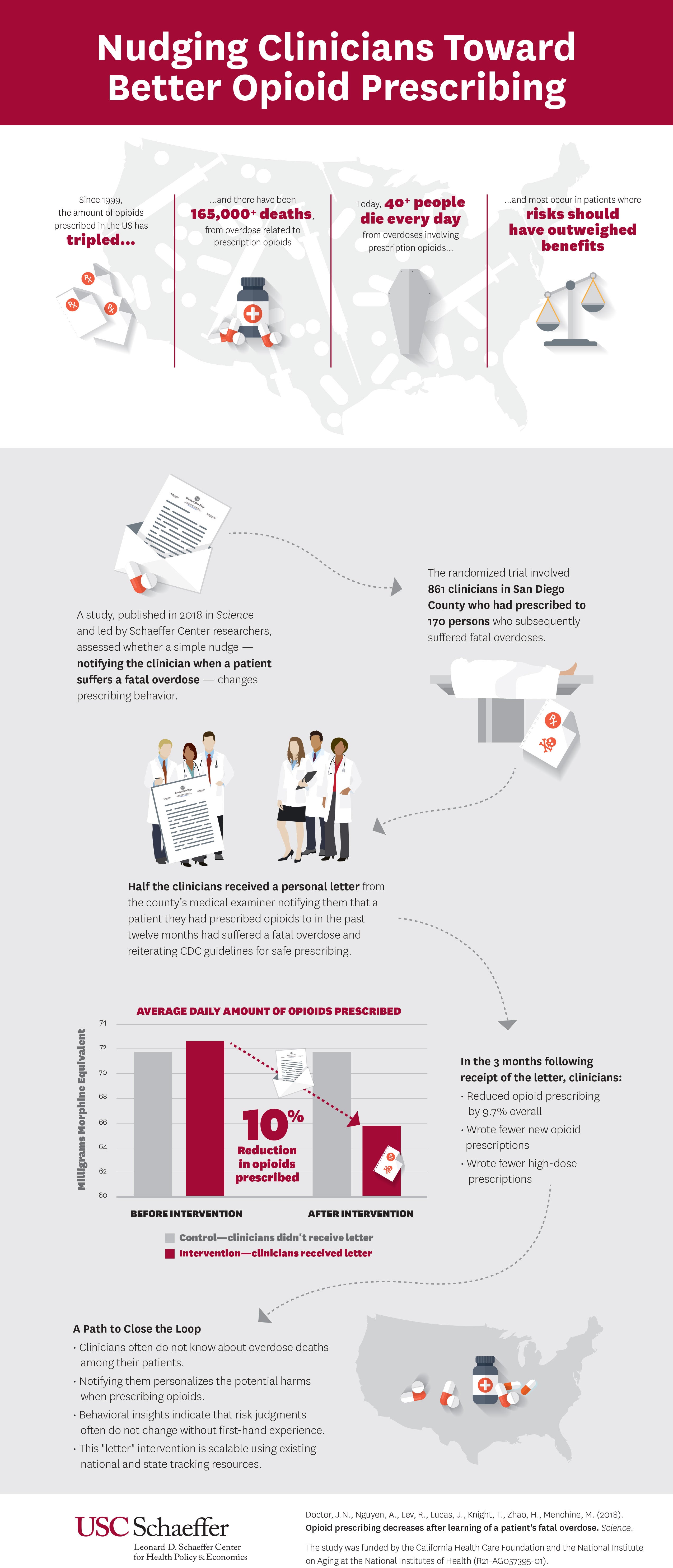

Will clinicians be more careful about prescribing opioids if they are made aware of the risks of these drugs firsthand? That was one of the key questions researchers explored in a new study published in the August issue of Science.

Researchers found that many clinicians don’t learn of the deaths of patients who overdose because they disappear from their practice with outcomes unknown.

“Clinicians may never know a patient they prescribed opioids to suffered a fatal overdose,” said lead author Jason Doctor, director of health informatics at the USC Schaeffer Center for Health Policy and Economics and associate professor at the USC Price School of Public Policy.

“What we wanted to evaluate is whether closing that information gap will make them more judicious prescribers.”

Opioid prescriptions: What is the risk?

The study gives prescribers a look at the risk associated with opioids, and finds that when a clinician learns that one of their patients had suffered a fatal overdose, they reduced the amount of opioids prescribed by almost 10 percent in the next three months.

Between July 2015 and June 2016, Doctor and his colleagues conducted a randomized trial of 861 clinicians who gave prescriptions to 170 patients who subsequently suffered a fatal overdose involving opioids. Half the clinicians who practiced in San Diego County were randomly selected to receive a letter from the county medical examiner, notifying them that a patient they had prescribed opioids to in the past 12 months had a fatal overdose.

The letter, which was supportive in tone, also provided information from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on safe prescribing guidelines, nudging clinicians toward better prescribing habits.

In the three months after receiving the letter, prescribing decreased by 9.7 percent compared to the control group which didn’t receive a letter.

In addition, clinicians who received the letter were 7 percent less likely to start a new patient on opioids and less likely to prescribe higher doses.

Impact versus regulations

The results are particularly interesting given that numerous, more traditional state regulations that often involve mandated limits on opioids have not been shown to have much impact.

The authors pointed to numerous reasons why this study showed promising results, including that the letters still allow clinicians to decide when they will prescribe opioid analgesics and that it provides an important missing piece of clinical information.

“Interventions that use behavioral insights to nudge clinicians to correct course are powerful, low-cost tools because they maintain the autonomy of the physician to ultimately decide the best course of care for their patient,” Doctor said.

“In this case, we know opioids, though beneficial to some patients with certain conditions, come with high risks that the doctor may not fully grasp when observing patients in the clinic. Providing information about harm that would otherwise go unseen by them gives physicians a clearer picture.”

Additional co-authors include Andy Nguyen, Roneet Lev, Tara Knight and Henu Zhao. Funding for the study was provided by the California Health Care Foundation and the National Institute on Aging at the National Institutes of Health (R21-AG057395-01).