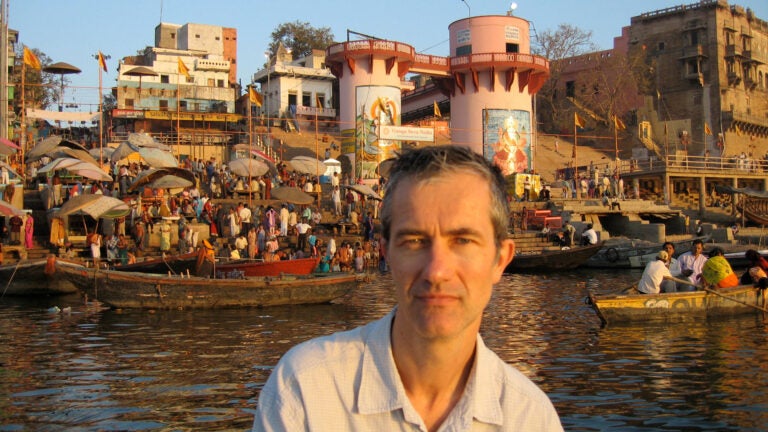

Geoff Dyer visits the banks of the Ganges in Varanasi, India. (Photo/Photo courtesy of Geoff Dyer)

For USC Dornsife’s writer-in-residence, a ‘gap year’ adventure changed everything

After years of unpacking his bags, author and globetrotter Geoff Dyer discovers that the journey can be as important as the destination

For a writer whose highly successful literary career is so largely inspired by travel, Geoff Dyer got off to rather a slow start in exploring the world.

Nothing predestined Dyer, writer-in-residence at the USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences, to be a traveler. In fact, the reason travel has been so important to his writing life, he said, is because it was not in his nature, or indeed his genes, to travel.

Dyer’s working-class parents, a sheet-metal worker and a school lunch lady, barely left their hometown of Cheltenham, England.

“My parents both died without ever having been on an airplane,” he said. “I didn’t get on an airplane until I was 22. We just never went anywhere, except occasionally on one of those dismal English seaside holidays. We never liked them.”

However, at the age of 8 or 9, Dyer’s parents did take him on a memorable outing to London’s Heathrow Airport, “not to catch a plane, but just to look at them” — an experience he found thrilling. Did he dream about boarding one and flying away?

“It was just so out of the question. I loved planes, but it never felt within grasp, really. So it wasn’t a frustrating thing, this trip; it was just a completely satisfactory end in itself.”

His other early exposure to travel came from a maternal aunt, a beauty who married a self-made millionaire and sailed on the Queen Elizabeth 2’s maiden voyage to America, then sent her young nephew brochures from Arizona’s Grand Canyon and Painted Desert.

“So some sense of another world was there,” Dyer said.

But it wasn’t until he arrived at what is known in Britain as his “gap year” — the period many British, and now an increasing number of American students take off between high school and university to travel overseas — that Dyer finally set foot on foreign soil. That he did so at all was only because a horrified high school English teacher pushed him to venture beyond British shores after discovering Dyer intended to spend the entire year working in an office in Cheltenham, his hometown on the edge of the Cotswolds.

The result was a somewhat arduous tour of Europe, squeezed into a Mini Cooper with two friends.

“I only went away for three weeks, so I really didn’t make the most of it,” he said regretfully of his own gap year — a rite of passage he is now convinced is highly beneficial.

“Despite it now being fashionable to deride it, if I were an employer and heard somebody had spent their gap year in Southeast Asia, I would still think it’s quite an impressive thing to do,” he said. “It requires a certain amount of intelligence and common sense, and in terms of broadening the mind, it’s just fantastic.”

Catching the travel bug

His own experience may have been too brief, but it served to give Dyer the travel bug. The following year, he tackled Greece. Since then he hasn’t looked back, describing travel as “an unalloyed positive.”

His desire to travel is, he said, intimately bound up with being a writer.

“After The Color of Memory [Jonathan Cape, 1989], my first novel, I didn’t really have that much more to say about Britain. So travel has given me the experience to write about,” he said. “I want to have been everywhere in the world at least once by the time I die.”

While Dyer’s dryly humorous writing is inspired by travel, he’s quick to point out that he would never describe himself as a travel writer, per se.

“I’m more of a writer about places,” he demurs from his spartan office in the USC Dornsife Department of English. “I can’t think of anything that’s been more important to me as a writer than place.”

But Dyer concedes that the journey can be as important as the destination.

“Quite often, it might happen that some incidental experience you’re having in the course of getting to a place is more important than what happens in the place itself,” he said.

This is the central conceit that informs the collection of essays about trips to diverse, exotic destinations contained in Dyer’s book White Sands: Experiences from the Outside World (Pantheon, 2016). It is often the act of getting there that turns out to provide the fascinating insight, the humorous anecdote, the philosophical revelation, while the final destination, more often than not, ends up being something of a disappointment.

Travel while you can enjoy it

Nevertheless, Dyer admitted that he still loves the feeling associated with a sense of arrival.

“Not just that ‘Phew, I don’t have to carry my bags anymore,’ but that sense of convergence that makes you feel this is what makes life worth living.”

Our planet is a pretty sensational place, he argued. It would simply be an incredible waste not to explore it.

Dyer warned against living as if we’re immortal, with endless time to travel, without awareness that things change. Once accessible destinations may become impossible to visit (Syria, for example), and our tolerance and endurance for challenging travel conditions usually diminishes with age. (One can imagine that Dyer, who is very tall, might no longer willingly tolerate the cramped conditions of the economy seats of his youth.)

“But the major danger of not traveling, I think, is that kind of narrow-mindedness and suspicion of the larger world, because actually, one of the amazing things, given the huge disparities of income, is just how honest people are,” Dyer said.

“Generally, we don’t actually have that much to fear from each other, and travel alerts you to that. It cannot but be a good thing.”