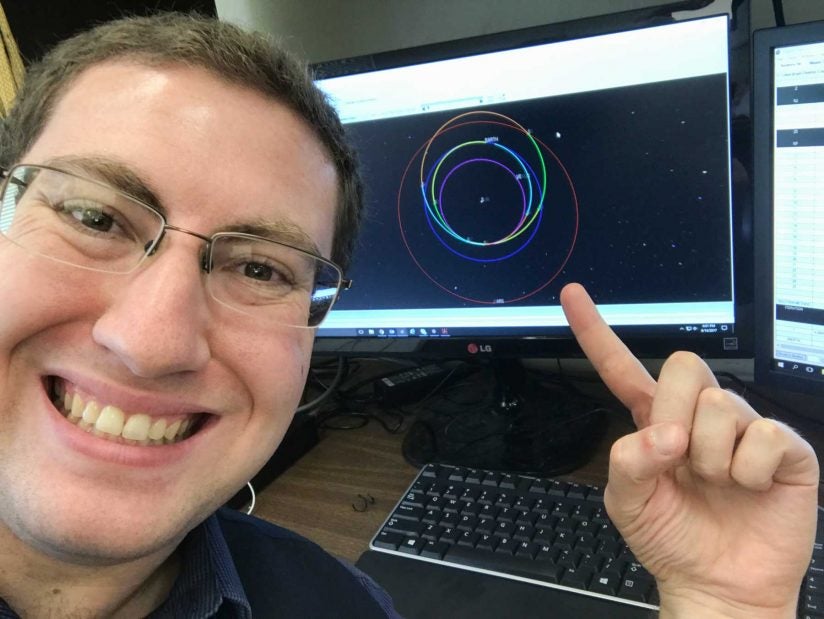

Things are looking up for doctoral student Joshua Fogel. (Photo/Courtesy of Josh Fogel)

Two-time NASA intern aims for the stars

USC Viterbi student helps work on trajectories for proposed space missions

Sitting in the flight director’s chair at Johnson Space Center’s historic Mission Control, Joshua Fogel MS ’14 listened as one of NASA’s most iconic phrases echoed through the room once more: “Houston, we’ve had a problem.”

Along with other interns at the Johnson Space Center, Fogel was watching the movie Apollo 13 in the very room where so much of it happened.

“It was so surreal,” he said. “I was sitting in the flight director’s seat, watching Ed Harris play Gene Krantz, who I just met.”

Fogel, a doctoral student in the Department of Astronautical Engineering, was interning at the center for the second time. Over the summer, he was one of four interns, from a cohort of more than 100, who was given the Outstanding Achievement Award for his performance and contributions at the center.

“We are very proud of our student,” said Mike Gruntman, Fogel’s academic adviser. “It validates that our educational program is focused on meeting real needs of space agencies and other large research centers.”

Maps in space

At the Johnson Space Center, Fogel was a part of the Flight Mechanics and Trajectory Design Branch, which deals with mission design and human space flight projects. Over the summer, he worked on creating and optimizing the trajectory paths of two proposed missions, which, as he described it, “is like Google Maps, but for spacecraft.”

One such spacecraft is a newly developed habitat capable of deep space transit using electric propulsion engines. It was designed specifically for future Mars missions. To test the vehicle, the Mars Study Capability team is exploring mission options prior to a Mars stay mission, which is currently scheduled for some time in the late 2030s.

One option is a triple-flyby of the inner solar system, dubbed “the Grand Tour,” in which the spacecraft will travel from Earth, to Venus, to Mars, back to Venus and then finally return to Earth. Fogel was tasked with seeing if this flight was even possible, as it was originally proposed in 1969.

It turns out that the trip is indeed possible. Similar to a Mars stay mission, it would take roughly 1,000 days and would include an opportunity for science or public outreach nearly every month as the vessel flies by asteroids, planets and the sun. To do so, Fogel planned a path that would loop the spacecraft around each of the planets, using their gravitational force to essentially sling-shot the craft onward, a maneuver made popular by The Martian.

“If you’ve ever seen the movie or read the book, you know the ‘Richard Purnell maneuver’ when they fly by Earth. That’s basically what I had to do but for multiple planets, which was really neat,” Fogel said.

He also worked on the upcoming Exploration Missions to the Moon, in which astronauts will travel aboard the new Orion spacecraft and construct a space station, named the Deep Space Gateway, that will orbit the moon. As these missions are designed, an important consideration is determining and planning for abort operations.

“If something goes horribly wrong on the mission — something blows up, you get hit by an asteroid, a crew member gets sick — if any of these kinds of scenarios occur, you may have to pull the plug and come home,” he said.

One worst-case scenario is the spacecraft becoming completely depressurized. Since astronauts have enough oxygen to survive in their space suits for just five days, Fogel had to find ways to get them back to Earth safely within that time period.

Coping with NASA’s Copernicus

As a PhD student at USC, his doctoral work mirrors his summer projects at the space center. For his thesis, Fogel is improving the orbit design capabilities associated with the low-thrust electric propulsion engines being developed by NASA. While he is still in the early stages, in the future his work could be used to improve trajectory design software, like NASA’s Copernicus.

“Copernicus is mostly used for human space flight, and so there are gaps in what that tool is capable of,” Fogel said. “Hopefully, that is where my thesis will someday fit in because some of the algorithms that I will develop will be able to be implemented in tools like Copernicus.”

Fogel hopes to one day work at the Johnson Space Center, designing space missions and perhaps even traveling to space himself.

But for now, after passing the PhD screening exam last January, he’s just concentrating on earning his degree.

“The analogy I like to use is: I fought all the way to get to the base camp of Everest, but now I’m looking up and I have to actually climb it.”