Students Immerse Themselves in the Past to Uncover Untold Stories

USC undergraduates go beyond the book to interpret history.

Anthony Garciano started crying.

Surrounded by old letters, documents and dusty clippings stashed in the archives of the Philippine Science High School in Quezon City, the USC history major felt an unexpected connection to Filipino history. Garciano’s family had left the Philippines when he was a child, and now, years later, he had returned there as a scholar to research the origins of Filipino nationalism.

What the USC senior wasn’t prepared for was the wave of emotions that hit him as he read a student’s letter published in an old school newspaper. Writing to herself, the schoolgirl recounted her life in 1965.

“She had been taken her from her home, placed in this school and asked to be a scientist,” remembers Garciano, who grew up in Independence, Missouri. “Reading how eloquently she wrote about her feelings touched me.” And to Garciano, reading the penned words while he was within the school that provoked them gave the letter even greater weight.

Many college students study history second hand, with classroom time spent discussing ideas and explanations crafted by established historians about wars, revolutions and cultural upheavals. But USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences’ history program prides itself on a more hands-on approach to give motivated students the tools to become historical detectives and develop their own, informed interpretations of the past.

USC students sort through libraries’ special collections and government archives and hunt down data in the seemingly limitless holdings of digital repositories. They scatter from China to Chile on fact-finding trips and go on geospatial explorations that enable them to virtually leapfrog across centuries or millennia. At USC, undergrads have the chance to find history’s untold stories and use their own voices to bring them to light.

MATERIAL WEIGHT

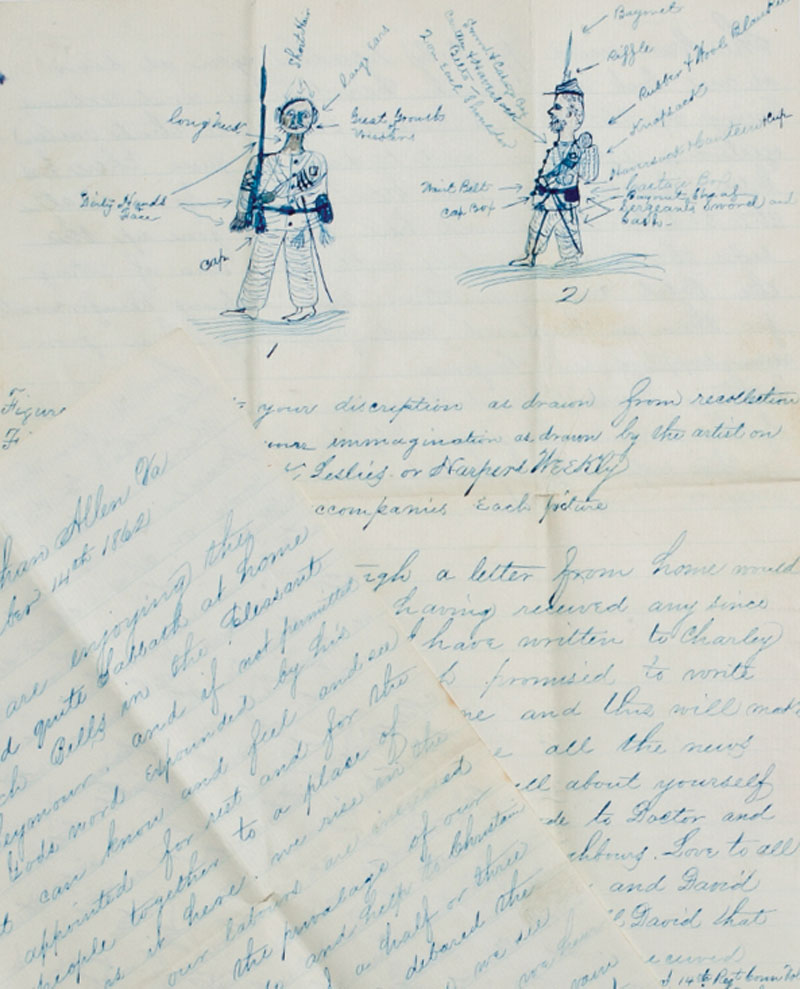

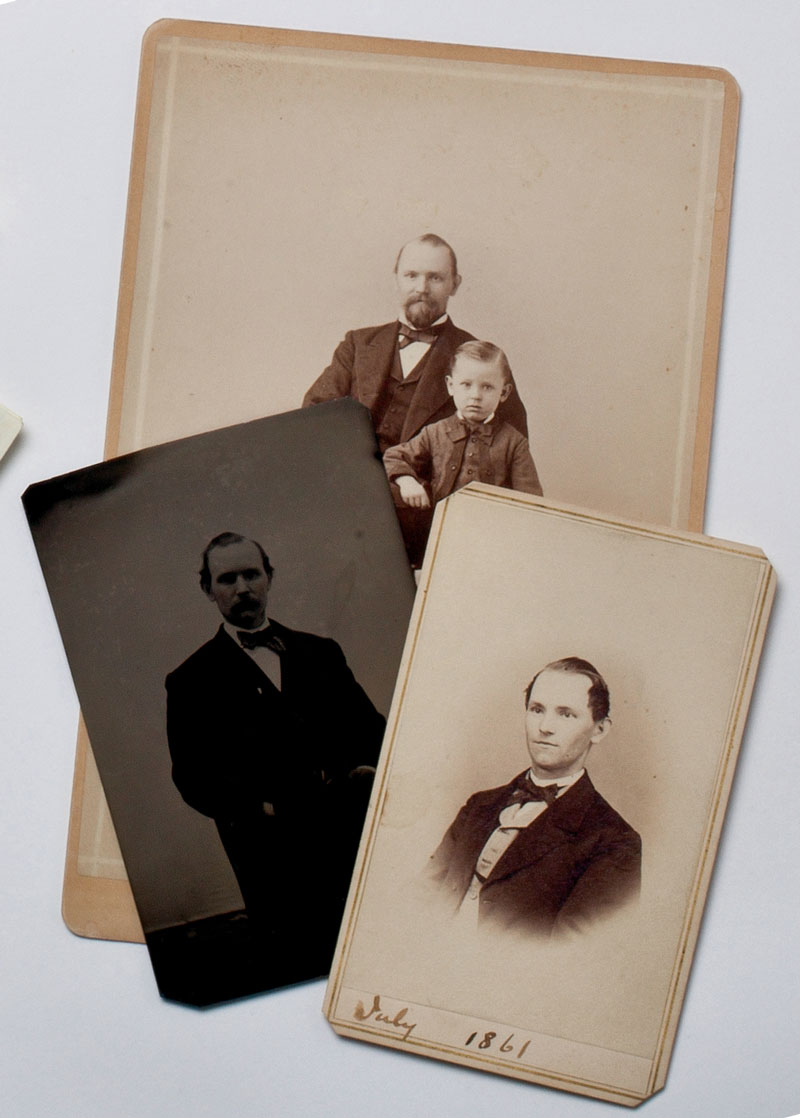

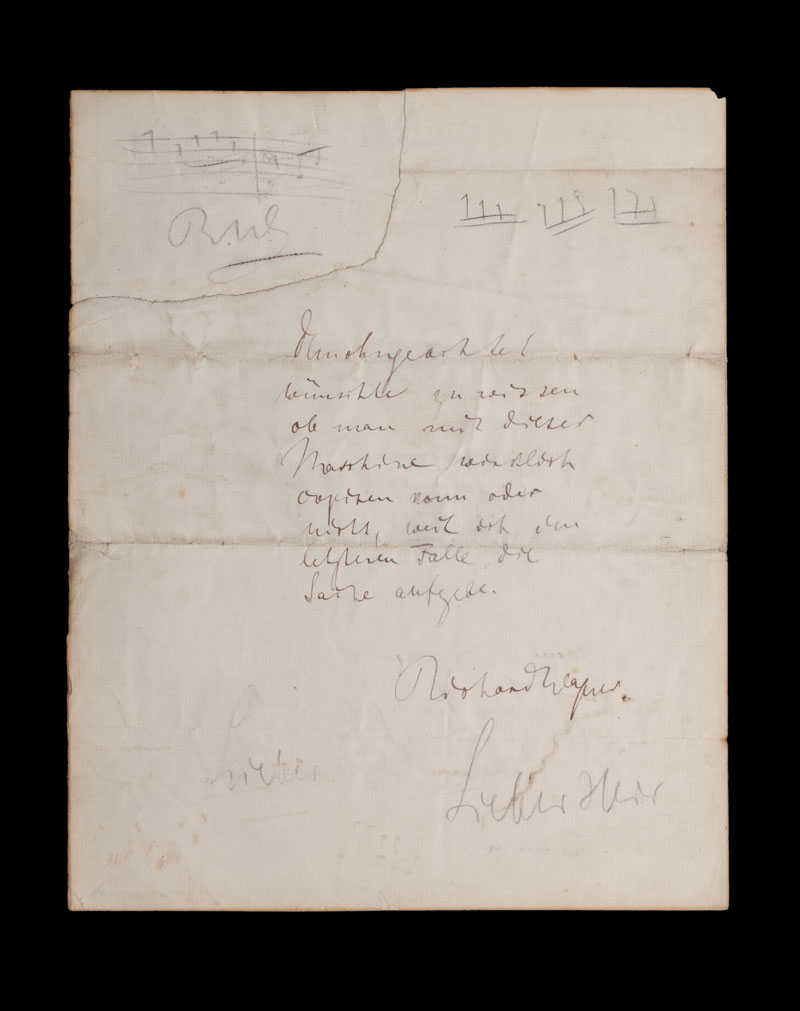

Archival research remains the gold standard for historians. There’s something about concrete objects—“their materiality,” says USC Dornsife’s Nathan Perl-Rosenthal—that draws people who analyze the past.

“I’ve held letters in my hand that were written by Abraham Lincoln,” adds Philip Ethington, chair of the history department. “It makes a difference.”

Especially for millennials born into a quasi-paperless world.

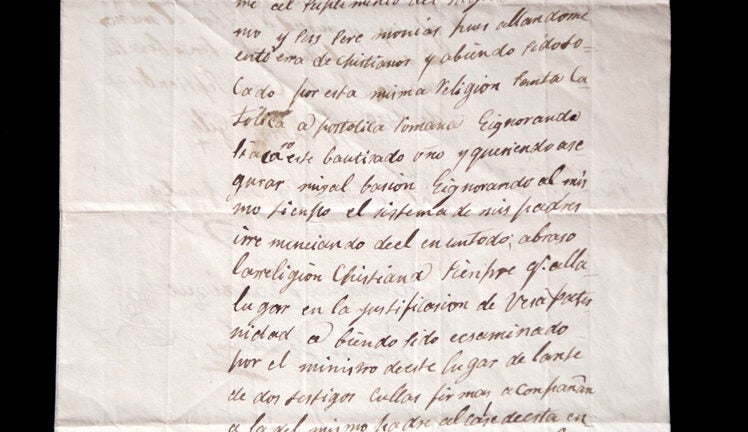

Perl-Rosenthal, who teaches history, remembers the excitement of a student who was working with letters written in the 17th century. Touching the parchment —absorbing its texture, shape and size, holding it up to the light to study an ink blot or the residue from sealing wax—yields unexpected insights and moments of clarity. Perl-Rosenthal knows this firsthand: His own scholarship on the 18th-century political and cultural life of Europeans and Americans leans heavily on epistolary primary sources.

For USC history major Madeline Adams, hearing the recorded voices of World War II-era Maori women talking about their lives made the racial and gender bias they had faced more real than reading interview transcripts ever could. “The tone and fluctuations in their vocal patterns made all the difference when analyzing the interviews,” says Adams, who traveled nearly 7,000 miles to New Zealand to access 1940s-era oral histories preserved on audiocassettes.

Her thesis focused on the societal costs of being both indigenous and a woman in 20th-century New Zealand. Adams is enrolled in History 492, the intensive scholarly writing class at the heart of the Department of History’s highly regarded honors thesis track. Taught last fall by Perl-Rosenthal, it consisted of six students. By graduation in May, each will have completed a capstone project of publishable quality and length, constituting an original contribution to the field of history. And based on the program’s track record, at least one of these projects will earn its author $10,000 from USC.

“We really love and are very proud of our senior thesis program,” Ethington says. “Its success is evident in the prizes these people are winning. Several have won the $10,000 Discovery Scholar prize, including my own advisees.” The coveted Discovery prize recognizes outstanding USC seniors for original scholarship that makes a significant contribution to their field.

TIME TRAVELERS

It’s a Wednesday afternoon on the University Park Campus and six honors thesis writers are sitting around a table in the basement of the Social Sciences Building. Perl-Rosenthal has a few suggestions for them about how to create a strong thesis introduction.

“You’ve read a ton of literature, thought about it, developed your own interpretation,” he tells them. “This is the moment to say: ‘There is a thing I know that other historians don’t know.’ You should feel confident about your argument, and I will continue to push you to express yourself in a confident way.”

The emotional, intellectual and writing help comes on the heels of significant financial support. Half the class traveled to far-flung places last summer thanks to the history department: USC history students can receive travel grants of as much as $5,000 through an endowment created by history alumna Roberta Persinger Foulke ’36, MA ’36. That’s enough to cover transportation, lodgings and living expenses while sifting through archives abroad.

“It’s hard to do serious historical research without doing archival research at some stage of the project, so having travel funds is a condition of possibility for doing serious work,” Perl-Rosenthal says. “In that regard, we are on par with Ivy League schools. The kind of funding our senior thesis writers get is at the same level.”

Some students’ academic curiosity kept them close to home. Krystal Cervantes, for one, has focused on how Chicano youth borrowed from the Civil Rights movement during the 1968 East Los Angeles Walkouts, which protested unequal educational opportunities for Mexican-American youth in L.A. classrooms. For her research, Cervantes camped out in the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center Library—the first in the U.S. to focus on people of Mexican descent—poring through box after box filled with hidden history: dusty periodicals, original prints, videos, slides and English and Spanish-language newspapers. She grew giddy with excitement, “like a kid in a candy store,” says the senior from Whittier, California. “You just open a box. You have no idea what you’re going to find!”

Classmate Zachary Larkin didn’t need to leave campus to study World War II-era Jewish resistance to fascism in Budapest. He found an abundance of primary-source materials through the extensive genocide survivor testimonies housed at USC Shoah Foundation—The Institute for Visual History and Education. Founded by USC Trustee Steven Spielberg, the archive has been housed at USC since 2013 and has more than 54,000 audiovisual eyewitness testimonies catalogued online and accessible from anywhere in the world.

Bethany Balchunas wanted to study race and French colonial policy in West Africa. Her honors thesis contrasts official records of the tirailleurs—more than 100,000 indigenous African infantrymen who fought for France during World War I—with fictional representations from period novels. So Balchunas traveled to Paris to consult colonial administrative records in the labyrinthine archives of the Bibliothèque Nationale, the national library of France. “Having access to the documents was so exciting,” she says, “and the archival staff were so kind. They searched through a billion different rooms to hunt down a document I needed on microfiche.”

As for Anthony Garciano, he is a recipient of a McNair Scholarship, which provides support to promising first-generation and traditionally underrepresented minorities preparing for doctoral education. For his thesis, he wanted to study the formation of Filipino national identity viewed through the eyes of gifted teenagers attending the Philippine Science High School. Launched in 1964, this government-run boarding school brought together gifted youth from across the newly independent Philippines. Far from their homes and families, the teenagers formed an academic community that, Garciano believed, could serve as a microcosm for his investigation into how an archipelago of 7,500 islands with 19 distinct languages became a unified nation. Learning history in the students’ own voices remains a powerful experience. “I completely felt what they were feeling,” Garciano recalls.

BEYOND THE BOOK

A cartographer and spatial scientist, Ethington delights in seeing students use interdisciplinary tools to explore history, like visual and map-based research. He spearheaded Scalar, a free open-access digital platform that’s changing how information- rich scholarship gets created and published. Through Scalar, scholars tell a historical story online using images, videos, maps, timelines and other visuals, and they can collaborate on the project even if they’re thousands of miles apart.

It’s no surprise, then, that instead of a term paper, the final project for Ethington’s History 240 “History of California” course is an assignment he calls “Los Angeles: The Movie.” Small teams of students build film treatments that span 1,000 years of regional history, from pre-Columbian time to the present day. Ethington’s own sprawling multi-genre history of the Southland, Ghost Metropolis: Los Angeles from Clovis to Nixon, is slated to be published this year in web and print formats.

Brett Sheehan, professor of history and East Asian languages and cultures, also has developed new technology tools to enhance his undergraduates’ learning experience.

His freshman seminar “Gaming Chinese Historical Capitalism” uses an online role-play game to take students on a journey through 200 years of Chinese economic and social upheaval. It took Sheehan a year to create the game China Times, with help from two USC game design majors. Dense scholarly readings come alive through gameplay, as students assume the identities of Chinese peasants belonging to six families. The goal: to grow the family’s wealth and social status over time as succeeding generations adapt from the rule of the last dynasty to republicanism, Maoism and today’s experiments with global market capitalism. Each financial decision players make has ripple effects over time. Should the family buy land, start a business, invest in a cash crop like tea, cotton or silk? Even personal choices—to seek an education, take a government job, make a marriage proposal—have economic consequences for the family.

History faculty don’t necessarily need to develop new software to be innovative teachers, however. They can use technology and resources already readily shared by researchers in the digital universe.

Ethington speaks glowingly of the wealth of such resources available through USC Libraries, and cites ProQuest as an example. This massive digital content collection available to students and scholars through the library system includes almost every newspaper, dissertation, journal article and government record published in the last 600 years—all sortable, word-searchable and downloadable from students’ laptops. ProQuest allows students to research information from primary sources quickly and thoroughly without having to flip through documents by hand.

For History 201, “Approaches to History,” Ethington recently challenged his students to document a potential American war crime—the firebombing of German and Japanese civilians during World War II. ProQuest searches in the Office of War Information archives indicate that the Pentagon knew these were criminal acts, Ethington says. Students then learned how to present such controversial information to the public in the form of reasoned, objective and documented argumentation.

While digital archives are hardly new, it’s only in the last five years that they’ve become user friendly.

USC’s Lon Kurashige remembers that as a graduate student in the 1980s, he needed a whole semester to access U.S. Census data stored on magnetic tape. “What took me a semester then, I could now do in 5 minutes,” says Kurashige, a professor of history and spatial sciences.

Adds Ethington: “It’s a wonderful time to be a historian.”

VISITING THE PAST

Massive digitization efforts by Western governments and cultural institutions have put a blizzard of primary sources within a keystroke’s reach. Physically being in Los Angeles, however, gives USC’s history students and faculty an advantage when it comes to sophisticated digital resources.

“The institutional ecology of L.A. is really rich,” Ethington explains, and USC’s history faculty play an outsized role in it. They direct a cluster of important institutes and research centers, including two with the Huntington Library, Art Collection and Botanical Gardens and another in conjunction with USC Shoah Foundation— The Institute for Visual History and Education.

USC history majors also benefit from a demographic advantage that students at many other big universities will never experience. “The entire world lives here,” Ethington explains. “Every major ethnic group has a big colony in Los Angeles.”

A professor who teaches Latin American history at USC, for example, can easily get students together with Bolivians, Peruvians or people from any other Latin American country. The same can’t be said of faculty teaching the course in a less diverse community.

Faculty members have another way to introduce students to living history: Ethington routinely takes his classes— including general education courses like History 100—on extended downtown Los Angeles walking tours. A 15-minute ride on the Metro train from USC’s University Park Campus carries students to the heart of downtown L.A. Ethington points out early movie houses and nickelodeons in what is today a working-class immigrant neighborhood, before taking the students to Bunker Hill, the Cathedral of our Lady of the Angels and La Placita Olvera. “By the time we’re done, they’ve seen a lot of history,” he says.

Sometimes the trips are more extensive. For the third year in a row, Kurashige, who is an expert on Asian-American history and transpacific history, plans to take a dozen students to Tokyo, Lake Yamanaka, Kyoto and Hiroshima in June for the course “Foreigner and Gaijin,” which explores what it means to be a foreigner in Japan. In Sheehan’s “Global Consumer Culture and China” course, students travel to megacities Beijing and Shanghai and provincial cities such as Zhengzhou and Hebi to study the uneven impact of globalization on consumption patterns in China. Assistant Professor Lindsay O’Neill’s travel course, “Sex and the City: Constructing Gender in London, 1700- 1900,” focuses on such gender-specific 18th-century British spaces as tearooms, boarding schools and gentlemen’s clubs.

In this unprecedented age of travel and digital information, learning and sharing history has increasingly grown beyond the bounds of the traditional book and the ordinary classroom. When passionate students are challenged to analyze historical evidence and spin arguments in original ways, they learn to view the world with a historian’s critical eye. They also grow a lifelong passion for the subject—as well as sharpen critical thinking skills that can serve them wherever they go.