Hot Enough for You? Why City Dwellers Say Yes—and What They Can Do About It

Cities are getting hotter, and that has dire consequences for our physical and mental well-being. The solutions? Community awareness and cooling strategies.

During a particularly brutal Southern California heat wave in September 2020, the Fonseca house in North Hollywood wasn’t just uncomfortable. It was downright life-threatening.

The temperature topped 111 in some parts of Los Angeles. To then-17-year-old Jenifer Fonseca and her family, it seemed even hotter. “I put my shirt in the freezer,” she says. The heat and the humidity irritated her little brother’s eczema and was dangerous for her siblings’ diabetic father. The house is air-conditioned, “but it’s too expensive to have on all day,” she says, “so we only do it when it’s majorly hot.”

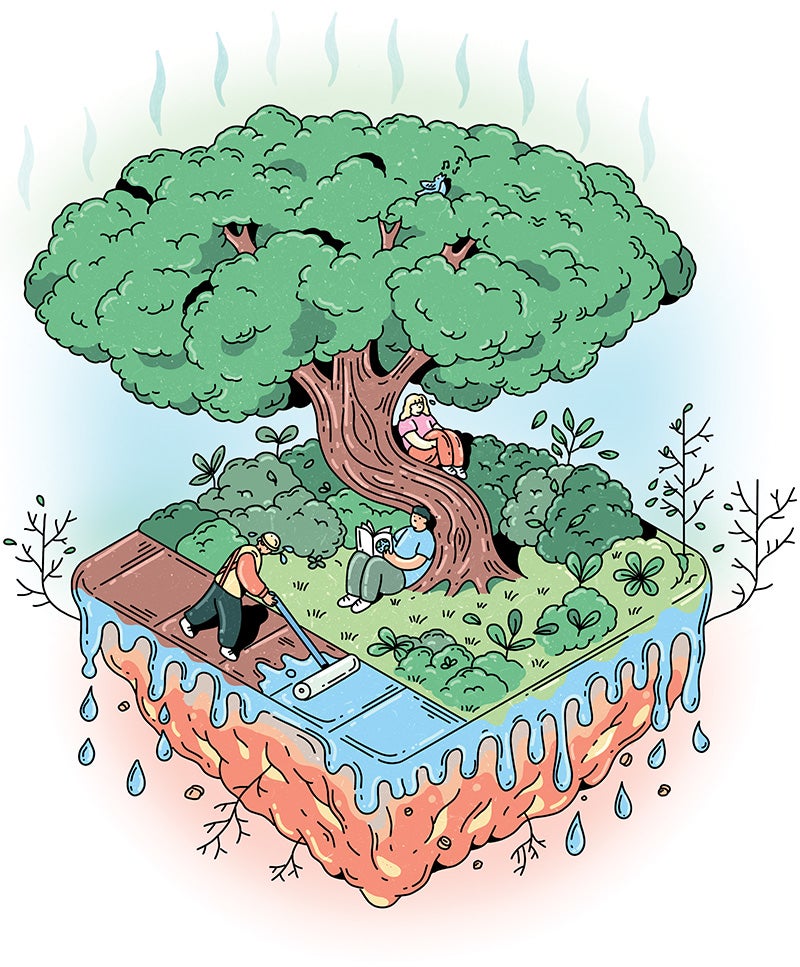

During oppressive heat waves, temperatures rise faster in big cities than in rural areas. But climate scientists are only just beginning to quantify dangerous spikes. Cities with heat-absorbing surfaces such as asphalt, buildings and dark roofs—and a deficit of trees and parks—create what is known as an “urban heat island effect,” zones in which temperatures are warmer than surrounding areas and are slower to cool at night.

In these islands, temperatures average one to seven degrees Fahrenheit hotter during the day than other places in the same geographic area and two to five degrees warmer at night, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). In some instances, temperatures in heat islands have registered as much as 27 degrees warmer than outlying areas, according to a 2014 study of 60 of the largest cities in the U.S. by Climate Central, a nonprofit organization that reports on climate change science.

Extreme heat, driven by climate change, is more than our bodies are designed to handle, exacting a physical and mental toll. Heat is the No. 1 weather-related killer in the country, causing heat exhaustion, heatstroke and heart attacks, according to the EPA. It fuels wildfires that produce toxic air, which can lead to respiratory issues and other health problems. Studies also show a significant increase in hospital admissions for mental or behavioral health disorders during heat waves, an increased use of emergency mental health services for depression and suicidal ideation, and an uptick in suicide rates, says Lawrence Palinkas, the Albert G. and Frances Lomas Feldman Professor of Social Policy and Health at the USC Suzanne Dworak-Peck School of Social Work.

The communities that face the highest burden of environmental pollution and who are most vulnerable to the effects of that pollution are also the same communities that have more pavement and fewer trees.

Jill Johnston

The health effects of urban heat islands disproportionately impact poor residents and communities of color, largely because of a practice called redlining, the discriminatory federal policies that deemed some neighborhoods poor real estate investments primarily because of their racial makeup, according to an October 2021 data analysis by the Los Angeles Times.

“The communities that face the highest burden of environmental pollution and who are most vulnerable to the effects of that pollution are also the same communities that have more pavement, fewer trees, are less likely to have air conditioning and are more likely to see and experience these extreme heat events,” says Jill Johnston, assistant professor of environmental health and director of community engagement in the environmental health division of the department of population and public health sciences at the Keck School of Medicine of USC.

USC researchers across disciplines, including public health, social work, engineering and architecture, are studying innovative ways to cool down and cope with our ever-warming planet. A crucial first step is to figure out just how hot it gets in L.A.

“Data that needs to exist doesn’t exist”

Johnston’s community engagement team was to begin distributing temperature sensors this spring throughout Pacoima, one of the hottest neighborhoods in the Los Angeles area. The team is seeking to answer the “how hot” question in collaboration with Pacoima Beautiful, a grassroots environmental justice organization that partners with the department of population and public health sciences.

The USC team will train Pacoima Beautiful’s staff and community members to log temperatures, ideally for a year, to identify patterns and answer basic questions about areas that experience extreme heat and areas where it’s cooler, and whether land use can inform actions that promote climate resilience.

“For us, a lot of the data that needs to exist doesn’t exist,” says Yesenia Cruz, youth programs director for Pacoima Beautiful.

During the first phase of USC’s collaboration with Pacoima Beautiful, community residents and staff placed air pollution monitors throughout the city. In Phase 2, they will collect temperature data.

“We know there can be drastic changes in temperatures” depending on land use, shading and trees, Johnston says.

I fear climate change. I feel sad that we’re basically ruining the Earth. That’s why I joined these programs, and I always bring my friends so we can learn what’s happening.

Jenifer Fonseca

“A lot of our work around climate change has been driven by community-based organizations where we provide tools so they can understand the science coming out and use that in their community organizing for healthy places to work and play.”

Fonseca, now a high school senior, won’t soon forget that miserably hot day in North Hollywood. She volunteered as a youth member of Pacoima Beautiful to fulfill her community service hours for high school, but the more she learned, the more determined she became to make a difference. “I fear climate change,” she says. “I feel sad that we’re basically ruining the Earth. That’s why I joined these programs, and I always bring my friends so we can learn what’s happening.”

Training students to be climate resilient

The mental health consequences of extreme heat are as varied as post-traumatic stress disorder, which can lead to depression and anxiety, and existential anxiety about the long-term impacts that young people like Fonseca face.

In a 2021 study, more than 45% of 10,000 participants from 10 countries ages 16 to 25 said climate change distress affected their daily life.

According to a 2021 study in the British medical journal The Lancet, more than 45% of the 10,000 participants, who live in 10 countries and are 16 to 25, said climate change distress affected their daily life. Seventy-five percent described their future as “frightening” and felt powerlessness, helplessness and guilt about the climate.

These feelings have names: “eco-anxiety,” extreme worry about the harm humans are inflicting on the environment; “ecoparalysis,” the inability to respond to the climate crisis; and “solastalgia,” the feeling of loss associated with the destruction of one’s environment, Palinkas says.

Palinkas and his colleagues are working to create climate-informed schools that address the physical and mental health needs of communities at risk for extreme weather. In partnership with the Los Angeles Unified School District and the USC Neighborhood Academic Initiative, they are designing an environmental health curriculum for middle and high school students, mental health services and training, and green neighborhood projects.

The hope is that having social workers trained in these interventions, and using them to prepare teachers and administrators for coping with acute events such as heat waves and longer-term issues such as eco-anxiety, can improve students’ mental health and wellness and simultaneously improve academic performance, Palinkas says.

“By offering these services in schools … in urban heat islands, we’re hoping we can use the schools as a health promotion platform in their respective neighborhoods so the benefits that accrue to the students … will eventually extend to [their] neighborhoods or communities,” Palinkas says.

Even a one-degree increase matters

An interdisciplinary project involving the department of population and public health sciences, the Dworak-Peck School of Social Work and the Viterbi School of Engineering is studying mortality related to heat and air pollution.

There is a large amount of scientific literature demonstrating an increase in health risks with increased temperature — even a one-degree increase.

Erika Garcia

“There is a large amount of scientific literature demonstrating an increase in health risks with increased temperature — even a one-degree increase,” says Erika Garcia, an assistant professor of population and public health sciences who is examining death certificates statewide to determine whether the cause of death correlates with the increased heat. “Even a small could impact a large number of people, including those vulnerable to health impacts of heat, such as the elderly, pregnant women and people with chronic health conditions.”

Scientists need to be creative and mindful of which groups the climate crisis is affecting disproportionately, Garcia says, including those working in restaurant kitchens or warehouses with no air conditioning, or people working outdoors who suffer from the heat.

“We’re not going to prevent this from happening—we’re already seeing hotter days and nights,” Garcia says. “Now it’s about adapting and protecting people and studying the problems so that the interventions we implement are useful and have an impact.”

Cool pavements, tree canopies

A team of USC environmental engineers, formerly led by the late George Ban-Weiss, is looking at heat-mitigation products, such as cooling pavements, roofs and other surfaces, says Kelly Sanders, associate professor of civil and environmental engineering.

“A good analogy is if you’re wearing a white shirt, you reflect a lot of the heat that you would otherwise absorb if you were wearing a black shirt,” says Sanders, Dr. Teh Fu Yen Early Career Chair in the Sonny Astani Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering. “It’s the same idea with heat-mitigation techniques.”

Cool pavements can reduce surface temperature, and more important, air temperature, says Joseph Ko, an environmental engineering doctoral student who is publishing a study on the topic. Pavements are cooled with a seal-coating material or made with concrete that has higher albedo—or solar reflectivity—levels. If less energy is absorbed in the pavement, less energy is released into the environment, he says.

But there are trade-offs and complications.

When cool pavements erode—because of natural soiling or vehicle travel—they reflect less sunlight and their heat mitigation efficacy is reduced, Ko says.

“There are also concerns that increased reflection of sunlight at the ground level may potentially decrease thermal comfort in certain scenarios, despite the reduction in air temperatures,” Ko adds. “These potential issues with maintenance and uncertain impacts on thermal comfort suggests that perhaps the technology has room for improvement and further investigation before real-world implementation.”

Mother Nature may offer a less problematic option: trees.

It can be 50 degrees cooler under the shade of a tree, according to the USC Urban Trees Initiative, led by the USC Dornsife Public Exchange. The interdisciplinary initiative provides a science-based guide for L.A.’s Green New Deal, which calls increasing, by 2028, the tree canopy in low-income heat zones.

People are waking up and recognizing that yes, our green space, our green infrastructure actually can make a significant impact on our physical health, our mental health and our climate resilience.

Esther Margulies

“People are waking up and recognizing that yes, our green space, our green infrastructure actually can make a significant impact on our physical health, our mental health and our climate resilience,” says Esther Margulies, associate professor of practice in the Master of Landscape Architecture + Urbanism program at the USC School of Architecture and a member of the Urban Trees Initiative. “Trees are the most cost-efficient way to combat extreme heat.”

But trees should be chosen for more than their seasonal beauty.

“Trees with sticky, hairy leaves are better at accumulating [fine particulate matter] than those with either smooth or sparse leaves,” Margulies says. “What we’re trying to measure is individual tree species with potential for air filtration in highly polluted areas because so many of our hot areas are also highly polluted from freeways and other sources.”

For Fonseca, who graduates from high school this year, environmental activism is more than a potential career choice in her future; it’s a necessary part of life.

Before joining Pacoima Beautiful and working with USC, she occasionally used Instagram to post about climate change.

“I just don’t think that’s enough now,” Fonseca says. “I’m not just a virtual activist. I actually go out there and do what I got to do.”