The Future of Digital Health Starts Here

Your smartphone could become as instrumental to your health as your prescriptions, and the USC Center for Body Computing is making it happen.

“What if you could monitor everybody all the time from their body computer?”

Cardiologist Leslie Saxon poses the question with an air of nonchalance, as if she’s merely asking how your day is going. But the question’s implications—and its answer—are perhaps as far-reaching as anything medical science has ever pondered.

If a computer designed to monitor your health 24 hours a day sounds like science fiction à la George Orwell’s 1984, consider that fitness watches are becoming ubiquitous and Apple and other tech giants are already getting into the business of tapping your health data. Apps on your phone or tablet can tell you to chill out when you’re anxious. But what Saxon has in mind goes beyond urging you to meditate or logging the steps you walk and the calories you burn.

Saxon, professor of clinical medicine at the Keck School of Medicine of USC, is founder and executive director of the USC Center for Body Computing. Headquartered at the Keck School of Medicine, the center works with private businesses, from tiny startups to multibillion-dollar biotech behemoths, as well as other USC schools and programs to bring on a revolution in personal health. Consider their mission a seismic shift: a potentially major change in our relationships with doctors, and a way to lower medical costs and help people enjoy longer—and healthier—lives.

The immediate future looks bright for wearable health and fitness tech. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration issued 23 digital health-related clearances for smartphone-connected medical devices and apps in 2014. One in five Americans plans to buy a wearable device, according to marketing firm Ipsos, and the wearables market is predicted to hit $12.6 billion by 2018.

But eventually, Saxon envisions, health devices won’t be worn; they’ll be implanted under the skin, where they’ll collect health information without the hassle of having to remember to put them on. (If that sounds far-fetched, consider that surgeons have been implanting pacemakers in patients’ chests for 60 years.)

Are you about to have a heart attack? How are your blood sugar levels? Your device could alert you if your numbers veer into dangerous territory.

The devices also will wirelessly share data with a central database that will analyze and compare numbers with those of thousands of other people. By combining your data with others’, the sensor networks could point out important patterns. For example, public health scientists could be notified if cancer rates spike over time in a neighborhood.

It’s wellness by way of crowdsourcing, and Saxon likens it to smartphone apps like the commuting tool Waze, which collects data transmitted from other Waze drivers and then calculates real-time traffic solutions based on the reports.

Saxon’s vision is far-reaching, but she’s not alone in her passion to bridge the digital divide between health and technology. Some ideas that were science fiction fantasy just a few years ago are now in everyday use.

Saxon’s vision is far-reaching, but she’s not alone in her passion to bridge the digital divide between health and technology. Some ideas that were science fiction fantasy just a few years ago are now in everyday use.

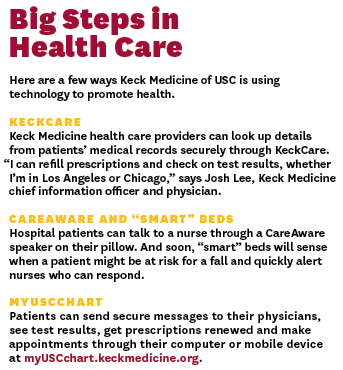

Keck Medical Center of USC provides secure work iPhones to help certain staff members more quickly access patient information when and where they need it. The program, which started in 2013 to save time and speed communication among those who care for patients, has grown to 500 devices across the hospital. The phones are securely linked with KeckCare, Keck Medicine of USC’s expansive electronic medical records system.

For Jesus Diaz, the ubiquitous smartphone can be an indispensible tool to help patients stay healthy at home. Take people confined to their beds or a wheelchair who are at risk of developing pressure ulcers, says Diaz, a research assistant professor in the USC Mrs. T.H. Chan Division of Occupational Therapy and Occupational Science. These ulcers can be treated easily when they first develop, but, left unattended, they can send a patient to the hospital with a serious infection.

With support from the Christopher and Dana Reeve Foundation, Diaz came up with an app—complete with a body map—that reminds people to check for these ulcers daily.

“The app will prompt you to take a picture of it so you can keep track of the progress of the sore,” Diaz says. It also provides recommendations to keep sores from becoming more serious and suggests patients call their doctor for an appointment.

Even if new technologies work flawlessly, though, privacy and data security remain an issue. With recent high-profile electronic security breaches at companies like Anthem, Sony and Target, will people accept having their sensitive personal information available to others electronically? Will they worry it might be shared without their consent, or that it’s susceptible to theft?

In most modern medical enterprises, personal health data are stored through secure electronic medical records. At Keck Medicine, “our data reside in a data center in Missouri within bunkers that are tolerant to an F5 tornado,” says Josh Lee, Keck Medicine’s chief information officer and a practicing physician.

Medical institutions and tech companies that work with hospitals and doctors must comply with HIPAA, the federal Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act—familiar to Americans for spurring those privacy forms you have to sign at the doctor’s office every year. It protects patients’ medical privacy rights. The government has accelerated its enforcement of the law, aggressively going after those who violate it.

But security becomes murkier when data used in smartphone apps are stored offsite in the cloud. HIPAA only protects privacy when personal health data from apps are shared with health care providers.

When Keck Medicine staff use phones to look at health information, none of the information is in the cloud, and “no data of yours are residing on a phone itself. All data are encrypted at rest and in flight,” Lee says.

“We use layers upon layers of protection.”

As medical providers begin to partner with companies to interpret patient data from smartphone apps like Apple’s HealthKit, Lee says, “we have an obligation to protect that data stream.”

Already, entrepreneurs like those at the Silicon Valley startup Medable are crafting tools that use data encryption and authentication to help developers ensure their health apps meet HIPAA requirements.

Patients’ data privacy also depends on a realm that’s outside technology and the law: the professionalism of everyone who has access to the data. “People confuse HIPAA with a locked safe, rather than being a framework of security,” Lee says. “It’s all about standards, practices and education.”

Keck Medicine ingrains a culture of respect among staff for patients’ health information, he adds. “We endorse the idea that you establish a relationship with your patient when you go into a chart.”

There’s always a balance of risk and benefit when it comes to sharing medical data, Lee says. Since a doctor can’t be with a patient at every moment, the health apps and technology pioneered by Saxon could extend some of the benefits of a care center to patients wherever they are.

Saxon believes the advantages of the digital health revolution far outweigh the potential negatives. And in the age of social media and instant access to information, she says, the very meaning of privacy is open for discussion.

Ultimately, it’s up to the consumer whether to use personal health tools and how to share the information. As Saxon puts it, “What would you give up if you knew you could live longer?”