Trojan Fulbright Scholars Gain a Global Outlook

More Trojans than ever are taking their studies overseas through a prestigious grant program—and many got their start through scholarships that draw top students to USC.

At only 22 years old, Maria Fish ’15 has a breathtaking collection of snapshots from places across the world: Chile, England, Honduras, Hong Kong, Macau and Spain, just to name a few. But these aren’t souvenirs of idyllic vacations.

There are the pictures of Fish as a teenage exchange student in Costa Rica and Honduras. More recent ones show her on Mexico’s Isla Contoy, taken during a tour of the national park to examine the effects of tourism on local ecosystems. Others show her in Valencia, Spain, where she traveled on a research award the summer after her freshman year at USC to study immigration policy. She looks at ease in the images: Traveling and working far from her Pacific Northwest home come naturally now. After all, she speaks Spanish and English fluently, and is learning Catalan. She’s also learned to embrace bridging language barriers and cultural differences as the best training to become a true global citizen—an education that can’t be acquired from any book.

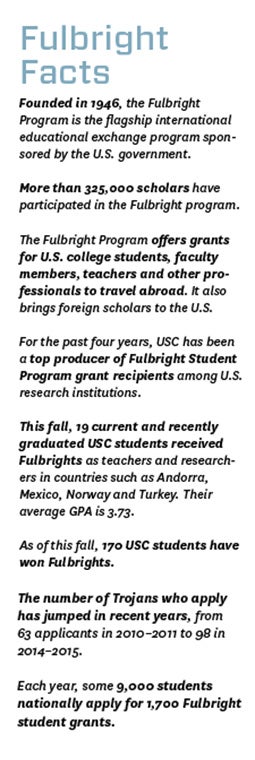

Her love for languages and life abroad made the USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences graduate a standout candidate for the prestigious Fulbright scholarship, which sent her to Europe this fall. The Fulbright U.S. Student Program stands as one of the oldest and most well-established international exchange programs, offering some 1,700 American students the opportunity each year to meet, work, live and learn in host countries around the world.

This year, 19 USC students won Fulbright grants, the largest Fulbright class in USC history, and USC has consistently been one of the nation’s top producers of Fulbright students. The exchange program fosters cross-cultural understanding across national boundaries through personal experiences. For USC, nurturing students like Fish in their quest to become citizens of the world is critical to making meaningful contributions to the larger international community.

Fish earned her Fulbright after a successful college career at USC. But like many of her fellow USC recipients, she got her first big break earlier—through the scholarship that made her a Trojan.

Far from home

It’s no accident that Fish, born in New York City and raised in Portland, Oregon, chose a college that enabled her to pursue her passion. USC’s school spirit and opportunities to study in Spanish-speaking countries, live in residential colleges and join diverse campus clubs convinced her that USC was the place for her. But another huge draw was her Trustee Scholarship, which covered her tuition for four years. USC grants Trustee Scholarships to about 100 outstanding entering freshmen annually based on achievement, community involvement, character and leadership skills.

“Without the generous support of USC fellowships and alumni and donor scholarships, I would absolutely not be a Fulbright scholar,” Fish says. “These experiences—offered and supported by USC—are what I believe set me apart from other applicants.”

Fish took advantage of the guidance available from the university’s dedicated staff in its Academic Honors and Fellowships office for students pursuing university awards and nationally competitive fellowships like the Fulbright.

When Fish was a junior, the Gold Family Scholarship underwrote her semester-long trip to Chile to deeply explore local culture and language. She studied human rights, Chilean politics and literature—in Spanish and with local college students at two universities—while living with a host family. USC Dornsife’s Summer Undergraduate Research Fund stipend funded her study of post-colonial cultural identities in Hong Kong and Macau through USC’s Problems Without Passports course. And Undergraduate Student Government sponsored her travels to Oxford University for a human rights course last spring.

Now her Fulbright scholarship takes her to Andorra, a country about the geographic size of New Orleans that’s nestled high in the Pyrenees mountains between France and Spain. Fish is the first USC student to win a Fulbright grant to teach English in the Catalan-speaking nation.

“I’ll be teaching English to 14-to-16-year-olds in the Andorran school system,” she says. She also hopes to volunteer with a local human rights organization and hike every marked trail in Andorra.

“I pursued a wide range of study abroad and international research programs at USC because I believe in the idea of global citizenship,” says Fish, who graduated with dual majors in Spanish and narrative studies. “I think intercultural understanding is the only way to create a more peaceful world.”

Though many Fulbright scholars are well traveled like Fish, their qualifications go beyond an oft-stamped passport. They’re distinguished for bridging international cultures.

Nick Kosturos ’15 wanted to gain a more global perspective his freshman year when he joined a Problems Without Passports research excursion. The San Mateo, California native soon found himself in completely new territory, examining Arctic security matters in Finland, Russia and Sweden.

“I was hooked,” Kosturos says. Taught by USC Dornsife’s Steven Lamy, professor of international relations, and Robert English, associate professor of international relations, the program brought students face to face with researchers and diplomats working on issues related to the militarization of the Arctic.

His Arctic adventure made such an impact that Kosturos switched from studying the Middle East and Arabic to Russian and post-Soviet languages, politics and cultures. His interest in Russia and the Cold War crystallized his post-graduation plans for study and work. “It has been a climate of innovation, going 100 miles per hour, since I was a freshman,” he says.

His enthusiasm led to a Fulbright grant to teach English and American culture for nine months in Belarus, starting this past September. Earlier this year, a U.S. Department of State Critical Language Scholarship funded his study of Russian in Vladimir, a city 110 miles outside Moscow.

In Vladimir—population 350,000— Kosturos lived with a host family in an apartment, studying Russian four hours each morning and speaking it nearly everywhere he went. Within months, his Russian had improved enough that he was able to have a two-hour-long conversation with a stranger on a train. His newly honed skills serve him well in Belarus, where the official language is Russian.

Most of the Russians he met over the summer were generous and kind, Kosturos says. “They are very welcoming, and very curious about the American way of life.” He hopes to continue this cultural exchange in Belarus, where he wants to organize small discussion groups at the local university to share ideas.

Like Fish, Kosturos traces his travels to Russia back to his exploration at USC—and the scholarship that started it all. “I can’t thank USC enough for these opportunities, all made possible through the Trustee Scholarship I was awarded and the funding of summer experiences,” says Kosturos, who hopes to pursue a career in foreign policy focusing on cybersecurity.

The opportunities didn’t end with his Fulbright: Kosturos was recently named a Dornsife Scholar, which grants $10,000 for graduate school after the Fulbright term is over.

Cross-cultural connections

The Fulbright recipients often tell personal stories that explain their international ties. Fish, for one, credits her interest in Spanish to her grandmother, who immigrated to the United States from Spain while that country was under the rule of Francisco Franco. When Fish was a child, her grandmother convinced Fish’s parents to enroll her in an immersion program so that she would learn Spanish and English simultaneously from kindergarten through high school. This foundation sparked her passion for languages and the idea of global exchange at an early age.

For Vivian Yan ’14, speaking Cantonese at home and growing up listening to her parents’ stories about life in Hong Kong widened her worldview. She was raised in Fullerton, in Orange County, California, but two visits to Hong Kong sparked her sense of intrigue and curiosity about that city. After Yan graduated from USC Dornsife with a double major in history and comparative literature, she decided to take her interest in transpacific Asian American history even further as a Fulbright student researcher.

She initially planned to spend her year at the University of Hong Kong in 2014 to study how Southeast Asian domestic worker activism has impacted ethnic and racial discourse in Hong Kong since the 1950s. But the timing of her trip meant that instead of reading about historic events in dusty archival documents, she got a firsthand view of social unrest and political protests as they unfolded.

“I knew the protests were likely to happen, which is why I wanted to go,” she says. “But the start of the protests shifted my research interest mainly to South Asian history in Hong Kong.”

Hong Kong’s “umbrella revolution” turned the city’s central business district into a protest zone, and tens of thousands of Hong Kong residents flooded the streets, demanding politically diverse candidates for the top governmental post.

Yan saw that Hong Kong’s immigrants from India, Nepal and Pakistan were much more engaged in the protests than the domestic workers she had expected to see. South Asians “didn’t just march and give speeches, but they proudly claimed to be ‘Hong Kongers’ just like the ethnic Chinese,” she says. “What made this special was that for the first time since 1851, the Chinese Hong Kong residents seemed to accept them as such.”

Yan quickly refocused her research to look at historical British-Indian-Chinese relationships, and their impact on creating racial discourses in Hong Kong, both under British imperial rule and now under Chinese rule.

“Like most people, I thought of Hong Kong as a place where Chinese migration is centered,” Yan says. “But the city is also an important place for Indians and other South Asians in their migration history.”

As a freshman Yan had been intrigued by cultural studies, but she wouldn’t have considered studying abroad without the early encouragement of Ramzi Rouighi, associate professor of history and Middle East studies at USC Dornsife. When she was a student in his modern Middle East history class, he encouraged her to connect to the broader world through travel and research. Yan had the qualities that make for a good study abroad candidate, so he suggested she apply to USC’s Problems Without Passports course in Kazakhstan, as well as a six-week program studying French in Paris. “She is self-motivated, curious, open to the world and unafraid to work hard to achieve her goals,” he says.

After returning from Hong Kong, Yan began doctoral studies in Asian American history at Stanford University in September, taking with her copies of the reams of historical documents she has collected about Hong Kong from the 1850s to 1970s. She plans to continue the research she began during her Fulbright.

Some five years after a Presidential Scholarship first brought her to USC as a freshman, Yan has clear career goals. “I want to be a professor,” she says. “I want to continue to study these issues. And I also want to pass on to other students the kind of support I received from my USC professors. Their mentorship made things possible for me I never dreamed of.”

Read more about USC fellowship programs at ahf.usc.edu.