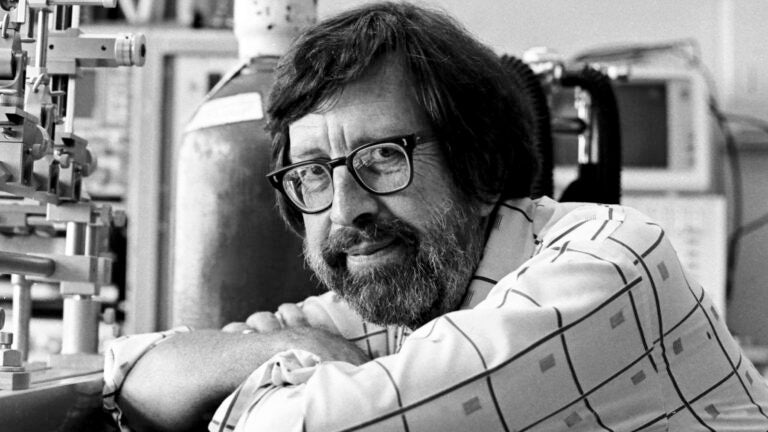

Neuroscientist Richard F. Thompson in 1987 (Photo/Irene Fertik, courtesy of USC University Archives)

In memoriam: Richard F. Thompson, 84

The internationally recognized behavioral neuroscientist spent a half-century on memory research

University Professor Emeritus Richard F. Thompson, a pioneer in neuroscience and holder of the William M. Keck Chair Emeritus in Psychology and Biological Sciences at the USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences, has died. He was 84.

Thompson, of Nipomo, California, died at home on Sept. 16 from natural causes.

“He had a happy, exciting and accomplished life, and we were honored to have him as a loving husband, father and grandfather,” his family wrote in a statement.

In a career spanning more than half a century, Thompson made seminal contributions to the understanding of the neurobiological substrates of learning and memory.

A pioneer of neuroscience

Regarded by many as the world’s leading authority in his field, he was the first neuroscientist to identify and map the neural circuits responsible for classical conditioning, or Pavlovian learning.

The USC community has lost a world-renowned scholar and an inspiring mentor, USC Provost Elizabeth Garrett said.

“As he helped to set the trajectory for modern neuroscience, Dick’s curiosity and aptitude across many areas of the sciences and humanities allowed him to answer some of the most difficult questions related to human behavior,” Garrett said. “Our thoughts are with his family as they remember our remarkable colleague.”

USC Dornsife Dean Steve A. Kay called Thompson’s work on memory groundbreaking in improving the understanding of neurological processes.

“His dedication both to his research and to the university helped raise the esteem of our Departments of Psychology and Biological Sciences,” Kay said. “Professor Thompson was a father in the field of neuroscience. His presence will be sorely missed.”

Thompson’s research focused on identifying places in the brain where memories are stored for particular forms of classical conditioning, a fundamental form of learning.

He showed that the brain saves a memory by strengthening the synapses, or connections between neurons. Neurons also create new synapses during the learning process, which Thompson defined as the creation of memory. His work also looked at the effects of behavioral stress, estrogen and aging on learning.

“Dick Thompson was a pioneer in physiological psychology, which he helped to transform into the field of neuroscience,” said Margaret Gatz, professor of psychology, gerontology and preventive medicine. “At USC, he essentially created the neuroscience program, where he recruited eminent faculty and was visionary in integrating computer science with psychology and neurobiology.”

An early innovator

Larry Swanson, Milo Don and Lucille Appleman Professor in Biological Sciences, said Thompson had been the intellectual leader of the USC neuroscience community since he arrived from Stanford University in 1987.

“Richard discovered the mammalian circuit for Pavlovian learning, and the breadth and depth of his thinking will be deeply missed,” Swanson said.

In 2002, Thompson was the first to identify and map neural circuits involved in classical conditioning, made famous by Russian psychologist Ivan Pavlov. More than a century ago, Pavlov’s classical conditioning theory showed that animals could be taught to anticipate an award.

Thompson tracked the memory traces that underlie Pavlovian conditioning to a tiny, specific part of the brain. Neuroscientists had been surprised to learn that the cerebellum, a dense ball of nerve cells at the bottom-rear of the brain, might play a role in learning and cognition. Prior to Thompson’s breakthrough research, the cerebellum had been considered a motor region — an orchestrator of voluntary, coordinated body movements.

Thompson was an exceptional mentor, guiding the careers of more than 60 graduate students and postdocs, many of whom are now senior leaders in the field of behavioral neuroscience.

Before joining USC, Thompson was a professor of human biology and psychology at Stanford, where he served as chair of the human biology program. Previously, he taught psychology at the University of California, Irvine, and Harvard University.

At USC Dornsife, Thompson served as director of the Neural, Informational and Behavioral Sciences Program from 1989 to 2001, then as senior scientific adviser to the Neuroscience Research Institute. His laboratory had continuous federal research grant support from 1959 to 2011, and he was instrumental in recruiting many leading neuroscientists, who collectively formed one of the nation’s first interdisciplinary neuroscience programs. Thompson was responsible for creating the Ph.D. program in neuroscience with William McClure, professor emeritus of biological sciences at USC Dornsife.

Thompson was an exceptional mentor, guiding the careers of more than 60 graduate students and postdocs, many of whom are now senior leaders in the field of behavioral neuroscience.

“He enjoyed students immensely in the laboratory,” said his wife Judith Thompson, who worked with Thompson for more than 30 years as a senior research associate. “His office was always open for consultations, and he talked with students all the time about their projects.”

A lifetime of learning and creating

Thompson attended Reed College, graduating in 1952 with a bachelor’s degree in psychology. Interested in science from a young age, he decided to enter the field after reading the books of famous American psychologist and behaviorist Karl Lashley. He earned his MS and Ph.D. from the University of Wisconsin-Madison. He met Judith at the University of Oregon Medical School, where they both worked in the psychiatry department.

Recognitions for Thompson’s scientific achievements include the Karl Spencer Lashley Award from the American Philosophical Society in 2007 and the American Psychological Foundation’s 2010 Gold Medal Award for Life Achievement in the Science of Psychology.

The author of numerous books and editor of several others, Thompson published 450 research papers. His first book, Foundations of Physiological Psychology (Harper & Row, 1967) has since become a classic in the field. He served as chief editor of the journals Physiological Psychology, Journal of Comparative and Physiological Psychology and Behavioral Neuroscience, which he also founded.

Thompson is survived by his wife of 54 years, Judith Thompson; his children Kathryn Thompson-Clancy, Elizabeth Collins and Virginia Thompson-DeWinter; and seven grandchildren — Matthew and Kristen Hitchman, Grace, Abigail and Lilly Collins, and Sabrina and Ryan Hetzler.

A funeral service will be held at Greenwood Cemetery in Bend, Oregon, on Sept. 25 at 1 p.m.