The 1950s – Powerful Years for Religion

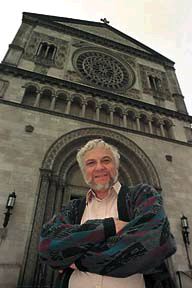

Robert Ellwood, on the steps of St John’s Episcopal Church at Adams Boulevard and Figueroa Street. On a typical Sunday morning in the late 1950s, almost half of all Americans were attending church, Ellwood said.

Robert Ellwood, on the steps of St John’s Episcopal Church at Adams Boulevard and Figueroa Street. On a typical Sunday morning in the late 1950s, almost half of all Americans were attending church, Ellwood said.

In 1957, when Robert Ellwood was fresh out of divinity school, he became pastor of an Episcopal church in a small town in Nebraska.

Although this church in the late ’50s was “a pale reflection of the celebrated suburban ecclesiastical powerhouses of the decade,” it mirrored some characteristics of the decade’s religious life, writes Ellwood in his new book, The Fifties Spiritual Marketplace: American Religion in a Decade of Conflict (Rutgers University Press, 1997).

Reflecting on his days at this “little church on the prairie,” the professor of religion recalls young families and children crowding Sunday school, vacation church school, church picnics and potluck suppers. Many of the men, the fathers of those children, were veterans of “the great and good war” that had ended only 12 years before.

“It was a fine time to go to church … and to build,” he writes. It was a decade when the American family was embraced as an institution by men and women seeking normalcy after World War II. The economy was booming and people bought nice cars and homes in the suburbs (the new feature of ’50s homes was the “family room”) and everything that went into them – from refrigerators to television sets.

However, beneath the normalcy and the focus on family and religion, tensions were brewing. In this companion to Ellwood’s Sixties Spiritual Awakening, The Fifties Spiritual Marketplace explores the major Catholic-Protestant tensions of the decade, the conflict between theology and popular faith, and the underground forms of ’50s religiosity – the interest in the “beat” poets and writers, Zen Buddhism, UFOs, Thomas Merton monasticism and the Joseph Campbell/

Carl Jung revival of mythology. Ellwood describes ’50s religious trends in the context of political events such as the Cold War, McCarthyism, the Korean War and the civil rights movement.

Ellwood contends that many of the trends – soaring birth rates, economic good times and the focus on normalcy and family – converged to create the religious boom of the 1950s. He characterizes the decade’s thriving organized religion as a supply-side phenomenon, in which suburbanites could almost always find a church of their denomination close by. His town in Nebraska, for instance, had perhaps a dozen churches of all sizes and types.

“It was the U.S. denominational society in action; few of those to whom it seemed so natural realized how strange and unlikely such an arrangement would appear in most of the religious world,” Ellwood writes.

The U.S. population achieved its biggest growth in history – from 150 million in 1950 to 180 million in 1960 – as newly married young couples begot the baby boom generation.

Churches and schools were being greatly expanded to accommodate the growing population, and organized religion was in its heyday. On a typical Sunday morning in the period from 1955-58, almost half of all Americans were attending church – the highest percentage in U.S. history. During the 1950s, nationwide church membership grew at a faster rate than the population, from 57 percent of the U.S. population in 1950 to 63.3 percent in 1960.

“Religion flourished in the ’50s for several reasons, partly because of the ever-expanding spiritual marketplace,” Ellwood said. “There were a lot of different options available that would appeal to different kinds of people. Before the war, organized religion was much more restricted,” he added.

While so many people were seeking to become the perfect American family – with their two children and two cars in the garage of their suburban home – in some ways, life in the ’50s was far from normal, Ellwood said. The nostalgic view of the 1950s has been glamorized in popular media and politics; the religious right recalls the ’50s in its “family values” debate.

But religious conflicts, especially in the early ’50s, were pronounced, Ellwood writes: Catholic vs. Protestant, “high” vs. “low” culture, mainstream vs. underground, liberal vs. evangelical. The early years saw McCarthyism and Korea. The Cold War was so ubiquitous that children fearing a nuclear explosion often did not believe they would grow to adulthood. Catholic-Protestant relations were strained by bitter altercations on issues such as parochial schools and public funding, and birth control.

The migration to the suburbs created a whole new way of life, revolving around mega-churches and stimulating writers such as Aldous Huxley to think about

the individual vs. mass society. During the later part of the decade, events such as the integration of schools in Little Rock, Ark., pursuing the mandate of Brown vs. Board of Education, fueled the nascent civil rights movement.

“This book deals with history, politics and culture, because religion is really inseparable from them,” Ellwood said. “If the book were only a history of denominations and institutions, it would not reflect what ordinary people were thinking and doing in regard to religion.”

Ellwood divides the ’50s into three periods: “The Years of Dark and Dreaming, 1950-1952,” “Shadows at High Noon, 1953-1956,” and “Signs Appearing in Heaven, 1957-1959.” In each section he documents the significant political, historical and cultural events, then discusses the important ideologies of the period.

In the first period, Ellwood focuses primarily on Sen. Joseph McCarthy, McCarthyism and the impact of the Cold War. He relates this movement to the nation’s religious trends – particularly McCarthy’s own religion, Roman Catholicism, and evangelical Protestantism. On another level, Ellwood argues that McCarthyism can be seen as a bid to create a sort of anti-Communist state church, complete with unquestioned dogmas and rites of exorcism.

The early period also saw the “flying saucer” phenomenon. Ellwood writes that “UFOism,” like all new religions, “combined signs and wonders in contemporary idiom with moral teaching attuned to the deep anxieties and dreams of the day.”

The years 1953-1956 represented the “classic ’50s,” said Ellwood. These were the years of fish-tail automobiles, the hula hoop fad and Elvis’ first big hit, Heartbreak Hotel. Debates over the moral issues involved in Korea, the Cold War and anti-Communism left many Americans untouched; they were more prosperous and better educated than ever, Ellwood writes. The period was marked by the downfall of McCarthy after the McCarthy-Army hearings in 1954, and the Supreme Court’s Brown vs. Board of Education decision, which declared segregation unconstitutional.

Ideologically, the middle of the decade saw a new movement toward spirituality, both in mainstream religion and the religious underground, and liberal reform Judaism was on the rise. This period also saw the emergence of beat writers like Jack Kerouac. Ellwood suggests that the beat movement was an outlet for ’50s males who turned away from the postwar family bonding.

“Fifties males felt deep, probably almost inexpressible, tension between the postwar nesting instinct and those restless other drives. Expressed in religious or quasi-religious ways, the alternative impulses helped shape the spiritual underground,” he writes.

By the end of the decade, the shift away from high ’50s religiosity began amid the double shocks of 1957: the integration of schools in Little Rock and the success of the Soviet satellite Sputnik. As mainstream religious revival waned, Billy Graham’s evangelical revival was on the rise. Ellwood writes that the Cold War and communism were less on people’s minds, as a new generation with different cars and rock music was coming into a new world – the 1960s.

He contends that the ’50s were the last decade of religious modernism, while the ’60s saw the beginning of a postmodern period. It was a time when religion was powerful in American life – partly because most people believed they needed it and there was seemingly nothing to discredit it.

“It was also because the varied spiritual marketplace proved dynamic and competitive enough to keep it going,” he said. “It was an age of affluence – sometimes a spendthrift age – in things of the spirit as well as of this world.”