Making sense of censorship, freedom of speech and ‘cancel culture’ in stand-up comedy

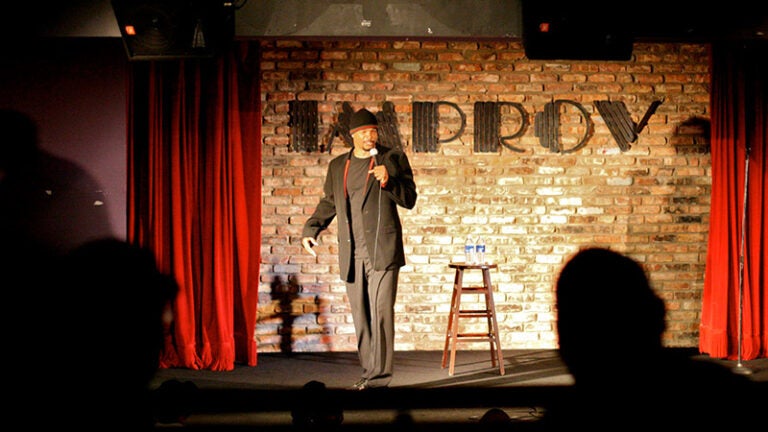

Stand-up comedy might be small in scope — a cast of one plus a microphone — but it’s wielded formidable influence over the years.

From Bert Williams, who paved the way for Black comedians, to George Carlin’s countercultural commentary to pioneering women like Joan Rivers’, stand-up comedians have often served as bellwethers for societal change.

Nowadays, stand-up frequently makes the news as a central discussion point in concerns over tolerating offensive opinions, “cancel culture” and freedom of speech. A recent Dornsife Dialogues event featuring USC scholars and hosted by Kristin Eggers, assistant professor of theatre practice in comedy performance at the USC School of Dramatic Arts, dove into the heart of the matter.

Controversial comedy: Many stand-up comedians are now experiencing fall-out after they preform controversial routines. This isn’t a new phenomenon. Comedians actually used to get arrested over their content.

- In the 1960s, Jewish comedian Lenny Bruce was arrested numerous times after his nightclub acts violated local speech laws in cities like San Francisco and Los Angeles.

Determining what can and can’t be poked fun of on stage is a source of rigorous debate in the comedy world.

What they’re saying: “Punching down” (directing jokes at those with less power) is often cited as the rule of thumb, but many comedians don’t agree.

- “[Comedian] Dick Gregory had said that part of your material is limited by your identity. If you’re a rich person, it doesn’t make any sense for you to make jokes about being poor,” says Cruz Arroyo, a PhD candidate in English at the USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences, who is studying the fictionality of stand-up comedy. “Nowadays, I think people get in trouble because they are joking about things that don’t even relate to them.”

- “We want to hear what [a comedian] has to say. It might offend us. We may disagree. But, we want comedians to have the latitude to say what’s on their mind,” says Wayne Federman, adjunct lecturer at the USC School of Dramatic Arts.

Find a transcript of this audio here under the transcript tab.

Audience participation: Comedy may have challenged social norms, but it has always adjusted as people’s sensibilities change.

- “For those of us who are in the audience of comedy clubs, some of the jokes that we may have laughed at 10 years ago, we’re not laughing at the same now,” says USC Dornsife’s Lanita Jacobs, associate professor of American studies and ethnicity and anthropology.

- Jacobs’ latest book, To Be Real: Truth and Racial Authenticity in African American Standup Comedy (Oxford University Press, 2022), explores notions of racial authenticity among African Americans through the lens of Black standup comedy.

The comedic art form continually evolves. Comedians either adapt to shifting tastes or fade away, to be replaced by someone who can make the audience laugh.

Going viral: The rise of social media has fueled stand-up comedy’s reach, as well as its potential to offend.

- Stand-up used to be limited to an in-person audience. Now, a cell phone can distribute a controversial act instantaneously, potentially generating a huge mob of outrage.

- But social media clips lose important context.

- “[People online] heard the punchline, but didn’t hear the setup. And since they don’t know anything surrounding this [joke], they’re not sure what to make of the comedian’s intentions,” says Arroyo.

- Arroyo says not all online outrage is genuine: “Outrage is very lucrative on the internet. You can get engagement, and engagement is money.”

Whom to watch: Our speakers shared the new comedians they are most excited about.

- “I’ll say the gentleman who availed himself for no less than two years to meet with me weekly to talk about stand-up comedy, Maronzio Vance,” says Jacobs.

- “There’s a comedian named Sam Morril who is starting to pick up a little bit. I think he’s a wonderful old school joke writer, very thrilling to watch,” says Federman.

- “Bo Burnham,” says Arroyo.