Pipe Dreams: How the West went from bathing daily to rarely and back again in 2,000 (mostly very stinky) years

Today, those of us living in first-world countries mostly take plumbing for granted, barely giving it a second thought unless we encounter the inconvenience of a blocked drain or leaking tap. But throughout most of Western history, plumbing was an alien concept. People lived surrounded by filth — their own and other people’s — and rarely, if ever, bathed, preferring perfume to mask the stench over contact with honest soap and water. Many paid the price, living shortened lives as a result of poor hygiene.

Perhaps then it’s no surprise that if we do pause to think about plumbing, we tend to consider it as a relatively modern invention. And yet, sophisticated plumbing systems actually first existed more than 6,000 years ago.

AN EARLY START

(Image Source: Wiki Commons.)

Two ancient cities, Mohenjo-daro and Harappa in the Indus Valley, in what is now Pakistan and northeast India, had advanced forms of plumbing by 4000 BCE that included drainage and sewage systems, sitting toilets and underground pipes to dispose of waste.

More than 4,000 years ago, ancient Egyptians used copper pipes to transport water and waste. Archaeologists excavating ancient Egyptian tombs even discovered toilets, presumably so the dead could relieve themselves. Eternity would be an awfully long time to wait, after all.

By 2000 BCE, the Chinese were transporting water via bamboo pipes. The world’s oldest surviving flush toilet — a stone seat over a channel of water fed by pipes — dates from the same period, and can be viewed on the Mediterranean island of Crete. A full bucket would have provided the flush action. The Minoans also enjoyed the luxury of running water and bathtubs. By 1500 BCE, ancient Babylon boasted drains and a working sewage system.

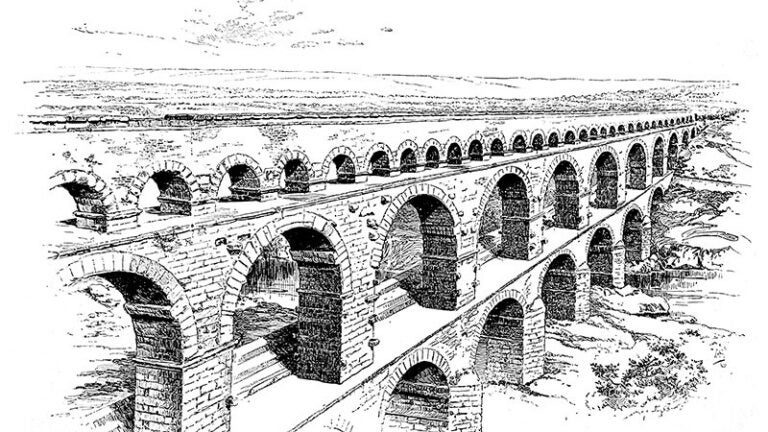

But the real trailblazers of modern plumbing were — of course — the Romans. Not only did they engineer towering aqueducts to bring water to Rome and the major cities of the Roman Empire, they also instilled a vibrant culture around bathing, building monumental communal baths. Their plumbing wizardry didn’t stop there. They installed latrines (also communal!) and constructed complex sewer systems to whisk away disease-causing human waste from densely populated urban areas. They even piloted sophisticated underfloor heating.

However, the Romans didn’t invent public bathing — the ancient Greeks take credit for that with their large gymnasia, where they favored energetic daily workouts followed by public ablutions in communal baths. But if the ancient Greeks enjoyed a brisk rubdown after working up a healthy sweat, it was the Romans who were responsible for turning bathing into a languorous art form.

“In terms of scale, no culture before or since has been as devoted to public bathing as the Romans,” says Ann Marie Yasin, associate professor of art history and classics at USC Dornsife.

Aqueducts delivered the equivalent of 300 gallons of water per person per day to Rome — “seven or eight times more than the average Roman needs today,” as author Bill Bryson notes in his history of private life, At Home. One house in Pompeii was discovered to have as many as 30 taps.

And this was true not just of Rome. “Aqueduct technology traveled where the Romans traveled and was considered one of the great hallmarks of Roman civilization,” Yasin says.

SPA DAY WAS EVERY DAY

Unlike the no-nonsense ancient Greek approach, daily bathing in the Roman world was more akin to the pleasures of a modern spa experience.

A ritualized practice, it involved passing through a series of variously heated pools, including the frigidariumand the caldarium. Along the way, Romans could stop at the unctorium to have scented oil massaged into their skin or proceed to the laconicum, or steam room, to work up a sweat before the oil and dirt were scraped off with a curved metal instrument called a strigil.

There was certainly no shortage of choices of where to bathe.

Urban census documents indicate that by the end of the first century BCE, there were close to 200 small baths in Rome. That number ballooned to more than 850 by the fourth century CE, including nearly a dozen thermae, or giant public imperial baths. Some of these larger baths were truly palatial in terms of scale and grandeur, accommodating up to 3,000 bathers.

Yasin stresses that bathing was only one part of what happened there. Larger public baths contained libraries, lecture halls, art collections, shops, brothels, gyms, snack bars, barbers and beauticians. People went to the baths to relax, socialize, conduct business, discuss politics, exchange the latest gossip, see and be seen.

“Unlike spectacle spaces, where seating was strictly segregated, at the baths all social classes may have mixed freely, from senators to slaves,” Yasin says.

“In terms of scale, no culture before or since has been as devoted to public bathing as the Romans.”

A NOT-SO-PRIVATE FUNCTION

(Image: © The Trustees of The British Museum.)

Our modern concepts of privacy weren’t shared by the Romans, who not only bathed together with joyous abandon but were also perfectly happy to use communal public latrines — often featuring at least 20 seats in intimately close proximity. Roman toilets may not have flushed, but a channel for drainage around the seating area did allow waste to be washed away.

“A very important part of the Roman concept of civilization and cities was the attention they showed to the drainage of sewage,” Yasin says. “Waste removal was frequently built into the network of a city, running alongside or under its streets. In Rome, the great drain, the Cloaca Maxima, drained the Roman Forum and ran out into the River Tiber, while other Roman cities boasted complex infrastructure systems that incorporated drainage.”

(Image: Courtesy of Trinity College Library, University of Cambridge.)

PLUMBING’S DARK AGES

While the Roman legacy of bathing continued to thrive in the East, particularly in the Byzantine and early Islamic worlds, the West was a different story. There, the practice was lost for centuries, replaced by a deep fear of water and mistrust of washing. The Roman emphasis on opening the pores for health and hygiene was superseded by the mistaken belief that pores should remain clogged with dirt to prevent deadly vapors from invading the body.

As the West descended into the Dark Ages, bathing became a rare, deliberately infrequent event — a lifestyle choice that didn’t bode well for peoples’ health, hygiene or olfactory receptors. As a result, life was frankly pretty grim for centuries. Only monks were fortunate enough to enjoy some respite from the ubiquitous filth.

“Plumbing went into pretty catastrophic decline as Roman infrastructure decayed,” says Jay Rubenstein, professor of history and director of the Center for the Premodern World at USC Dornsife.

The vast majority of cities lacked any kind of sophisticated plumbing and were still dependent on wells or fountains for the water they needed to drink, bathe and extinguish fires.

Why did monasteries fare better?

“Central to monastic life were rituals of purification that required access to a reliable water supply,” Rubenstein says. But questions of ritual aside, he notes, managing enclosed communities of a hundred or more people provides a very real incentive to figure out a way to get clean water in and wastewater out.

“As a result, complex water systems began to make a comeback around 1200, developed from knowledge gleaned from rural religious communities and imported to cities,” Rubenstein says. “The techniques they employed harken back to Roman plumbing. It’s just possible they were able to consult technical guides, but more probably they rediscovered the technology themselves or brought it back from Italy.”

Inevitably, as he points out, there’s a lot of guesswork involved where medieval plumbing is concerned due to the lack of poetry and great art being produced on the subject during the Middle Ages.

One exception is the Eadwine Psalter. At the back of this lavishly illustrated book of psalms dating from 1155 is an unexpected document: a detailed, two-page pullout diagram of the plumbing of Canterbury Cathedral. Showing what is probably one of the most sophisticated plumbing systems of the time, the map details how spring water was piped in, irrigating apple orchards and a vineyard, before being raised to a water tower that gave it the necessary momentum to flow through the monastery.

“Most of the medieval latrines I’ve seen dropped into tunnels that also served as escape routes. That could make for rather a dramatic escape if you had to get out in a hurry.”

Water spouts from spigots decorated with dragon or animal heads, and a necessarium (latrine block) is topped with a statue of a lion. The infirmary is shown to be sensibly equipped with a separate necessarium for the sick and the monastery with a designated place to wash one’s hands before entering the choir and handling the Eucharist.

This all begs the question: Why are plumbing plans included at the back of a holy book?

The simple answer is to provide a map for repairs. But Rubenstein argues that it’s there because it’s all part of God’s work.

“The church is a big community. And organizing it is a huge task,” he says. “Building a water system is part of that administrative achievement and is as much an act of piety as building an altar.”

But despite the new water systems, people remained largely steadfast in their resistance to bathing for the next 650 years.

“Wash your hands often, your feet seldom and your head never,” was a common English proverb, while Queen Elizabeth I was said to have bathed once a month “whether she needs it or no.”

Bryson notes that in 1653 the diarist John Evelyn recorded “a tentative decision to wash his hair annually,” while Louis XIII of France went unwashed “until almost his seventh birthday in 1608.” As for one of the first great woman travelers, the 18th-century aristocrat Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, Bryson recounts how a new acquaintance blurted out his amazement at the grubbiness of her hand after shaking it. “‘What would you say if you saw my feet?’ Lady Mary responded brightly.”

PURIFICATION AND HEALING

But if the West was wallowing in its own filth for centuries, this was not the case in the East, particularly in Japan, which has a long and illustrious history of bathing. The Korean spa culture that is so popular today can be traced back to Japan’s influence during the colonial period of the early 20th century.

One reason that Japan became so focused on cleanliness lies in its topography: Two thirds of the world’s hot springs are located in Japan, providing a convenient supply of endless hot water. These springs are traditionally believed to come with the additional benefit of healing properties due to their high natural mineral content. The other reason for such an early focus on bathing is religious belief.

“These springs have been regarded as a sacred landscape for so long because of the Shinto tradition — the indigenous pre-Buddhist religious culture of Japan,” says USC Dornsife’sDuncan Williams, professor of religion, East Asian languages and cultures and American studies and ethnicity.

“There are two components to the history of bathing in Japan: purification and healing, and they go hand in hand.”

“While today we might investigate claims of spring water’s healing powers by using science, back then they were simply viewed as miraculous,” Williams says. “Throughout Japan, many of the oldest hot springs have religious connotations because of their supposed healing powers.

“There are two components to the history of bathing in Japan: purification and healing, and they go hand in hand.”

In Japanese culture, water and salt have long been the two main substances used for purification. Families who have experienced a death will pile salt outside their homes while water will be used to purify the body or the home after a disaster or unfortunate event.

(After the Bath by ItÃ…Â Shinsui.)

Once Buddhism became established in Japan in the eighth and ninth centuries, Buddhist temples were designed to comprise seven structures, one of which was required to be a bathhouse — a concept that originated in China.

“Buddhist sutras, or sacred texts, devoted to the bathhouse would talk about the cleansing of one’s body, but also what they called the cleansing of one’s ‘moral, or karmic defilement’ — an idea that also came from China,” Williams says.

Indeed, bathing was so popular in Japan that by the 17th and 18th centuries, guidebooks were published listing the country’s best bathhouses and hot springs.

By the 18th century, Japanese city planners were already thinking about how to prevent what they saw as the two biggest threats: fire or a pandemic spread through poor sanitation and lack of hygiene.

“As a result, in terms of sanitation, access to bathhouses, and technologies of cleansing and dealing with sewage, Japanese city planning was very advanced in that period compared to other parts of the world, including European capitals like Paris or London,” Williams says.

However, that didn’t mean that people necessarily had bathing facilities in their own homes, he notes.

“From as far back as the ninth and 10th centuries in Japan, when people would visit Buddhist temples to bathe, even up to when I was growing up there in the 1970s, not everybody had baths in their homes. Instead, they would visit a neighborhood communal bathhouse, or sento,” Williams says.

Today, the vast majority of Japanese homes have their own bathrooms. More than 80% are also equipped with Japan’s high-tech sanitation products that frequently include built-in bidets and heated seats. These high-end products have had a global impact, making the country a world leader when it comes to matters of plumbing.

MIASMA

All this is a far cry from the early-Victorian era. Before flush toilets, people were dependent upon chamber pots, outhouses, cesspits and the visits of the “nightsoil men” who disposed of human waste, often by selling it for fertilizer, in what must undoubtedly have been one of the least enviable jobs of all time.

The system worked — sort of. But as London grew, so did the city’s noxious odors and the Victorians’ concerns about disease, which they firmly believed was caused by “miasma” that floated over the city like a bad smell.

“They were convinced that something that smelled disgusting could actually produce disease,” says Lindsay O’Neill, associate professor (teaching) of history. “Indeed, leading Victorian sanitary reformer Edwin Chadwick insisted to an 1846 parliamentary committee that ‘all smell is disease.’”

Thus, cholera, dubbed “the poor man’s plague,” was attributed to miasma when it swept through Europe in the early 19th century. It wasn’t until a deadly outbreak in 1854 in London’s Soho that investigators finally discovered its root cause, thanks to the inspired detective work of one man: John Snow.

A leading anesthesiologist, Snow became suspicious that the outbreak had originated at the Broad Street Pump, source of the local water supply.

“That blows people’s minds because the Broad Street Pump was always thought to be particularly clean,” O’Neill says. “But Snow figured out that the common thread between those who got sick and died was that they had consumed its water.”

A nearby institution that suffered no cases — a brewery where workers preferred their beer ration to water — was the outlier that supported his hypothesis.

Snow’s deduction — a radical departure from the widely accepted miasma theory — caused considerable conster-nation at the time. But after Snow removed the pump handle, no new cases occurred. The pump was eventually discovered to have become contaminated when the walls of a nearby cesspit disintegrated.

THE GREAT STINK

This episode got Londoners thinking more critically about the cleanliness of their water supply, resulting in the creation of a Metropolitan Board of Works in 1855.

Little progress was made, however, until the advent of the wonderfully named “Great Stink” of 1858, which forced the government’s hand.

“It’s a great story of trying to control the uncontrollable city through sewage.”

The problem for the growing city, as O’Neill points out, had always been: Where do you put all the waste?

“Especially as Londoners began to embrace the flush toilet, much of it ended up in the Thames, which went from being a relatively pleasant river to London’s cesspit,” she says.

The unusually hot, dry summer of 1858 caused the Thames to run exceptionally low. Despite dipping the curtains of the Houses of Parliament in chloride of lime in a vain attempt to protect its members from the horrendous odors rising from the refuse- and waste-clogged river, the affront to the olfactory system was so intense that Parliament could no longer work. As The Times reported on June 17, “Parliament was all but compelled to legislate upon the great London nuisance by the force of sheer stench.” By Aug. 2, it had passed a bill to fix London’s sewage problems.

(Image Source: Wiki Commons.)

Sir Joseph Bazalgette, chief engineer at the Metropolitan Commission of Sewers, was hired to construct a sewage system. “Sanitation has never had a greater champion,” Bryson notes. Between 1858 and 1865, Bazalgette oversaw the construction of more than a thousand miles of pipes to deliver London’s waste far enough down the Thames (although not quite far enough in the opinion of those living near the outfall pipes) that incoming tides wouldn’t send it back toward the city.

“A stroll along the Thames in London now entails walking along the Victoria and Albert Embankments, constructed around the Victorian period to hold those big sewers,” O’Neill says. “The physical landscape of London we’re familiar with today is actually due to these pushes to control sewage.”

Ornate pumping stations were also built at the tidal outflow.

“They were Victorian palaces, built to celebrate their control over steam power, but also their control over waste,” O’Neill says. “It’s a great story of trying to control the uncontrollable city through sewage.”

THE GREATEST NAME IN SANITATION

Victorian critical thinking about sanitation and cleanliness also created the impetus to replace cesspits with water closets.

The fortuitously named Thomas Crapper, a Victorian sanitation engineer and creator of the U-bend, has often been erroneously credited with the invention of the modern toilet.

“Crapper is probably not as important in the development of the flush toilet as we would like him to be,” O’Neill says. “But he’s there at the point when its development and plumbing for all is really exploding from the mid-1850s to the 1880s.”

In fact, the flush toilet was actually invented three centuries earlier by Sir John Harrington, godson to Queen Elizabeth I. For centuries, latrines had existed in castles as tiny rooms equipped with a seat that allowed waste to drop into ditches or, alternatively, the moat — the latter option providing an effective additional deterrent to any enemies who might unwisely consider breaching the castle walls by swimming across.

“Most of the medieval latrines I’ve seen dropped into tunnels that also served as escape routes,” Rubenstein says. “That could make for rather a dramatic escape if you had to get out in a hurry.”

When Harrington demonstrated his prototype to the Queen in 1587, Elizabeth was by all accounts delighted with her godson’s invention — until he made the fatal error of composing a humorous essay on the subject. Elizabeth was not amused, and without royal patronage, his invention fell out of favor. It lay forgotten for almost 200 years, until cabinetmaker and locksmith Joseph Bramah revived the idea, patenting the first modern flush toilet in 1778. Twenty-three years later, across the Atlantic, Thomas Jefferson installed three of the nation’s first flush toilets at the White House, powered by rainwater cisterns in the attic.

THE GREAT CLEANLINESS MOVEMENT

Victorians first encountered the novelty of flush toilets at the Great Exhibition of 1851, where more than 800,000 people patiently stood in line at London’s Crystal Palace to experience them. They proved such a resounding success that by the mid-1850s, some 200,000 had been installed in homes across the country.

But while affluent Victorians enthusiastically adopted water closets, ordinary people still lived in appalling filth. People continued to empty chamber pots out of bedroom windows. Streets and basements were awash. Even after effective sanitation became widely available, many people continued to show considerable resistance to soap and water. We may forget that until the 20th century, access to water indoors was rare, even in major Western cities. Bathing was not normalized and thus was often seen as unhealthy, O’Neill notes.

“Bathing … was only one part of the understanding of cleanliness. Neatness and unadorned clothing were as — if not more — important.”

“Bathing was done out of the house and, especially starting in the 1500s, bathhouses were often seen as sites of sin. Even when Methodist founder and cleric John Wesley, who is commonly seen as the wordsmith behind ‘cleanliness is next to godliness,’ pushed for bathing toward the end of the 18th century, it was only one part of the understanding of cleanliness. Neatness and unadorned clothing were as — if not more — important,” O’Neill says.

Today, we think of bathing as a pleasant way to relax, but that wasn’t the case for the Victorians.

(Image Source: Ahrens & Ott Manufacturing Co. 1896.)

In fact, Bryson writes what finally convinced Victorians to adopt bathing was “the realization that it could be gloriously punishing.”

Showers were designed to be as ferocious as possible. One model, he notes, required users “to don protective headgear … lest they be beaten senseless by their own plumbing.”

America went on to lead the world in the provision of private bathrooms. Europe lagged behind, largely for reasons of space — and cost. By 1940, Americans could purchase a bathroom suite for $70 — a price within the reach of most. But by 1954, as Bryson notes, only one French home in 10 had a bath or shower, and for many worldwide, a bathroom was — and still remains — an unattainable luxury.

So, the next time you luxuriate in a hot bath, slake your thirst by drinking a glass of safely filtered tap water, or simply flush the toilet, remember our good fortune — and the billions worldwide who still don’t have access to what we in first-world countries take for granted: the comfort and lifesaving wonders of modern plumbing.