Thirty years later, the beating of Rodney King and the shooting death of Latasha Harlins continue to reverberate in Los Angeles and throughout the country. (Photo/iStock)

‘Like a stick of dynamite’: USC scholars reflect on legacy of 1992 L.A. uprising and police beating of Rodney King

USC experts remember the events that led up to the violence and protests, and consider more recent violence against Blacks including George Floyd and Eric Garner and fatal confrontations between vigilantes and Black citizens.

It was the one of the first videos of anti-Black police violence to go viral, long before Facebook, Instagram and Twitter — before George Floyd and Eric Garner became household names.

In March 1991, Black motorist Rodney King was beaten by four members of the Los Angeles Police Department. The brutal beating — filmed by George Holliday from his apartment balcony — appeared on local television, then national news, eventually leading to charges against the police.

One year later, in April 1992, a jury acquitted the officers charged with assault with a deadly weapon and excessive use of force against King. The city erupted into several days of civil unrest, protests and violence that resulted in thousands of people injured and more than 50 people dead.

Erroll Southers was a police officer with the Santa Monica Police Department in 1991, and he recalls the rising tensions.

“L.A. was ready to explode before Rodney King,” said Southers, who is now USC’s associate senior vice president of safety and risk assurance. “And then the trial happened. It was the tipping point. It was just like a stick of dynamite that was lit and thrown into a ship that was full of dynamite.”

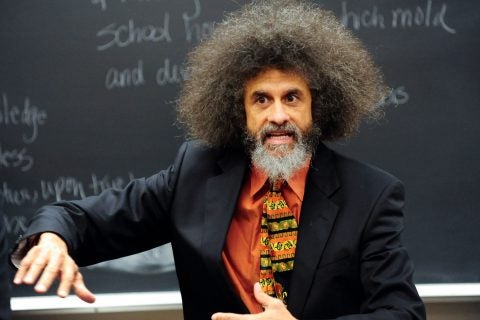

At that moment, the justice system had lost its legitimacy and “moral credibility in the eyes of many Black and brown Angelenos,” said Jody Armour, the Roy P. Crocker Professor of Law at the USC Gould School of Law and an expert on the relationship between racial justice, criminal justice and the rule of law.

“Along with the rest of Black America, Black Angelenos did not erupt in rage when the videotape of the Rodney King beating first hit, then saturated, the airwaves,” Armour recalled. “They waited for our justice system to make good on its promise of equal justice for all under the law.

“It wasn’t until that promise seemed so flagrantly flouted by the Simi Valley jury’s acquittal of the four officers that a violent revolt erupted in the streets of L.A.”

Americans remain familiar with Rodney King because of that infamous viral video. The civil disturbances that followed the officers’ acquittal are often referred to as the “Rodney King riots.” Community activists say another name from that fraught period should also be remembered.

Just days after King’s beating, a 15-year-old Black girl named Latasha Harlins was killed by a Korean-American convenience store owner over a $2 bottle of orange juice. An accusation of theft escalated into a physical confrontation and shop owner Soon Ja Du shot and killed Harlins as the girl headed for the store’s exit.

Police later said there was no evidence the girl was shoplifting. Her family and community were devastated by the killing and the fact that Du — like the officers who’d beaten King — served no prison time. In 1992, Du’s sentence to five years’ probation and community service was upheld by an appeals court. That was one week before the verdict in the King case.

Thirty years later, both stories continue to reverberate in Los Angeles and throughout the country.

“Joan Didion said, ‘We tell ourselves stories in order to live,’ and that is really what’s kept Black folks going in this country,” said Allissa Richardson, assistant professor at the USC Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism and the author of Bearing Witness While Black: African Americans, Smartphones and the New Protest #Journalism.

“Our stories help us mark time and show that we have made progress — that things are changing.”

Richardson spoke as part of a panel discussion on storytelling and its symbiotic relationship with public policy titled “The Lasting Influence of Latasha Harlins, Rodney King, and the 1992 L.A. Uprising,” moderated by Southers and organized by the USC Black Alumni Association; the Center for the Political Future at the USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences; the USC Price School of Public Policy; and the USC Price Safe Communities Institute.

“Our stories also help all Americans understand there have been overlapping eras of domestic terror against Black folks, from slavery to lynching to mass incarceration,” Richardson said. “We tell these stories so people understand that racism and the way white supremacy manifests itself is persistent; and to make sure that progress continues.”

Other panelists included Rodney King’s daughter Lora King and Latasha Harlins’ cousin Shinese Harlins-Kilgore, along with the Rev. Najuma Smith-Pollard, assistant director of community and public engagement with the USC Dornsife Center for Religion and Civic Culture.

The Black church takes center stage in L.A. activism

For Smith-Pollard and many in the Black faith community, the uprisings were a turning point.

“Many of us hadn’t lived through that before,” she recalled. “I lived in the heart of South L.A., but that was the first time I saw tanks and military in the streets. If you were out at a certain time, there was the threat of getting arrested.

“Everybody needed therapy.”

Smith-Pollard’s therapy was throwing herself into her church’s efforts to serve the community during and in the immediate aftermath of the unrest. The First African Methodist Episcopal (FAME) Church became “the spot where things were happening” — feeding and clothing people in the community and providing counseling and financial assistance, she said. “It became the mecca of church and public service from Sunday to Sunday with no days off.”

Soon after, Smith-Pollard accepted her own call to ministry and was mentored by the Rev. Cecil “Chip” Murray — a transformative pastor at FAME who grew the small congregation of 250 into an 18,000-member church. “It created the model for other L.A. churches to step into faith leadership, civic engagement and community and economic development,” said Smith-Pollard.

That legacy would be further cemented in the Faith Leaders Institute at USC’s Cecil Murray Center for Community Engagement, which brings together clergy and lay leaders of faith-based organizations and empowers them to become advocates.

Rodney King’s was among the first, but not the last widely seen video of anti-Black violence

Thirty years later, Americans continue to reckon with police violence against Black men and women — and with vigilantes who assume the role of law enforcement. The latter includes George Zimmerman, a neighborhood watch captain who shot and killed 17-year-old Trayvon Martin a decade ago in Florida.

Although Zimmerman wasn’t convicted, the three white men in Georgia who chased and killed Black jogger Ahmaud Arbery in February 2020 were recently found guilty. So too, was former Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin, who knelt on the neck of George Floyd as he begged for his life. The video evidence in these cases played an important role.

These families matter. Their lives matter. And our stories matter.

Allissa Richardson, USC Annenberg

“These families matter. Their lives matter. And our stories matter,” said Richardson, who noted that Darnella Frazier — who filmed George Floyd’s murder — was given a special Pulitzer citation. According to the Pulitzer committee, the Black 17-year-old girl’s video “spurred protests against police brutality around the world, highlighting the crucial role of citizens in journalists’ quest for truth and justice.”

Efforts to address racism in policing and society continue

Floyd’s videotaped murder, like King’s beating, was a pivotal moment. In his role as director of the Safe Communities Institute, Southers co-founded the Law Enforcement Work Inquiry System (LEWIS) Registry, the first comprehensive national catalog of police officers who have been terminated or resigned due to misconduct. He announced the registry on the one-year anniversary of Floyd’s murder, during continued Black Lives Matter protests against police violence.

“The only way to change the culture is to remove the people who are problematic to that culture,” he said. “This is something that is going to benefit communities and it’s going to benefit law enforcement. I think it’s going to keep people safer.”

For his part, Armour believes the LAPD has more work to do. “The 30th anniversary of the L.A. uprising presents a chance for us to collectively reflect on the causes and consequences of one of the largest riots in American history,” he said. “Part of LAPD’s reckoning with the racial injustices that propelled the ’92 riots must be its recognition of its role in over-policing Black communities through unnecessary traffic stops, chases and crackdowns.”