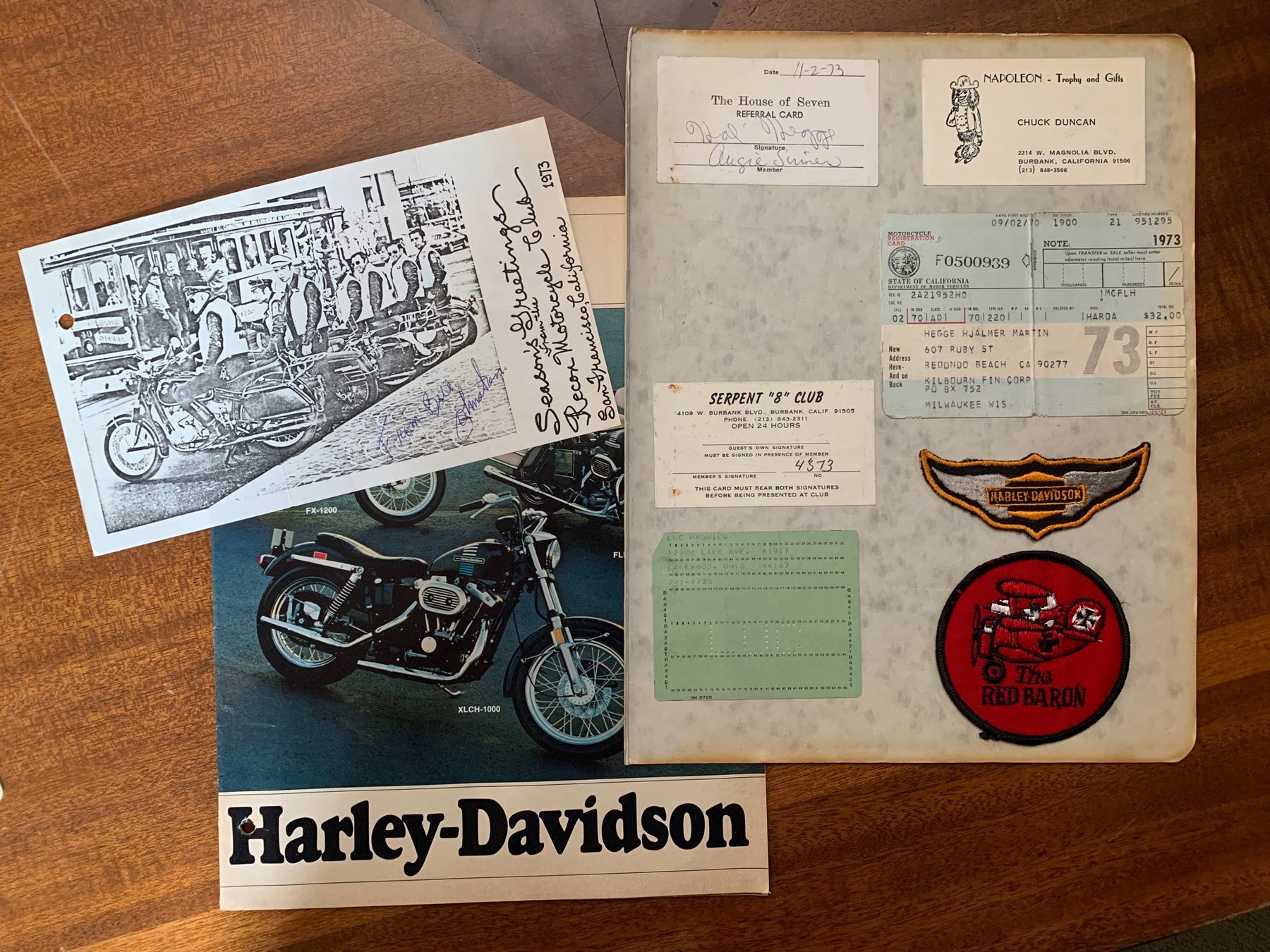

Five Blue Max Motorcycle Club members in uniform jackets and Pickelhauben helmets seated on Harley Davidson Electra Glide motorcycles in Glendale circa 1970. (Image/USC Libraries)

Stories from L.A.’s pioneering gay motorcycle clubs are told through USC’s ONE Archives

USC has the largest archive of LGBTQ materials in the world, and researchers use it every year to learn more about gay history and culture.

They climbed over hills on the outskirts of Los Angeles atop their Ducatis and Triumphs, hearing only the growl of their motorcycle engines and the whistling Santa Ana winds. The men’s uniform: black leather jackets and tight jeans.

Patches on their jackets didn’t read Hell’s Angels or Mongrels. Instead, they rode with clubs like the Satyrs, Argonauts, Warriors, Blue Max and Oedipus. In 1950s L.A., these men would meet in secret locations for days of riding, drinking and brotherhood.

Patches on their jackets didn’t read Hell’s Angels or Mongrels. Instead, they rode with clubs like the Satyrs, Argonauts, Warriors, Blue Max and Oedipus. In 1950s L.A., these men would meet in secret locations for days of riding, drinking and brotherhood.

They belonged to some of the country’s first gay organizations: gay motorcycle clubs. The Satyrs, founded in 1954, remains one of the oldest continuously operated gay organizations in the United States. Today, gay men can meet openly, but during the ’50s, these clubs were some of the only places they could gather safely without fear of discrimination or violence.

The history of these clubs may not be widely known, but it’s a critical narrative in LGBTQ history — and it has a home in the ONE Archives at USC. Part of USC Libraries, the ONE Archives is the largest repository of LGBTQ materials in the world. During Pride Month — and all year long — LGBTQ stories from the past can be studied and shared through the materials in the collection.

“There’s a whole history that people don’t know about,” said Joseph Hawkins, director of the ONE Archives.

Gay motorcycle clubs: from fear to freedom

The first gay motorcycle clubs were born during the height of McCarthyism. Most remember the McCarthy era as a time when the government persecuted suspected communists. But some officials also sought to root out gay men, lumping them in with communists and fearing they could be blackmailed into exposing state secrets.

There’s a whole history that people don’t know about.

Joseph Hawkins

These clubs formed in an age where gay people were forced to live in the shadows. They were one of the few places where gay men could come together. As society embraced the tough biker image — movies like Rebel Without a Cause were popular — the clubs also served to counter homophobic stereotypes that questioned gay men’s masculinity.

“Motorcycle clubs were a way of saying gay men can be more masculine than straight men,” Hawkins said.

Motorcycle clubs grew in the midst of incidents like the infamous Black Cat tavern episode of 1967. That’s when plainclothes Los Angeles police officers infiltrated a Silver Lake gay bar and beat patrons as they celebrated New Year’s Eve.

By the late ’70s, L.A. had more than 20 gay motorcycle clubs. They were so popular that as many as 400 men would attend their annual parties.

Each club had a unique identity and traditions, some known for their elaborate costumes or wild parties.

Oedipus, for example, had a reputation for having elaborate “coronation” events where they elected a new “Rex,” or club president. Blue Max was known for its members’ buzzworthy antics, like the time they rode around dressed as nuns or showed up to an event nude on their motorcycles.

The clubs also helped cultivate some of the early seeds of gay activism in Los Angeles, years before the Stonewall riots in New York City.

In their early years, the clubs met in Hollywood’s Carolina Pines Banquet Hall, which was nicknamed Motorcycle Hall. Years later, civil rights activists from PRIDE, or Personal Rights in Defense and Education, would meet in the same location.

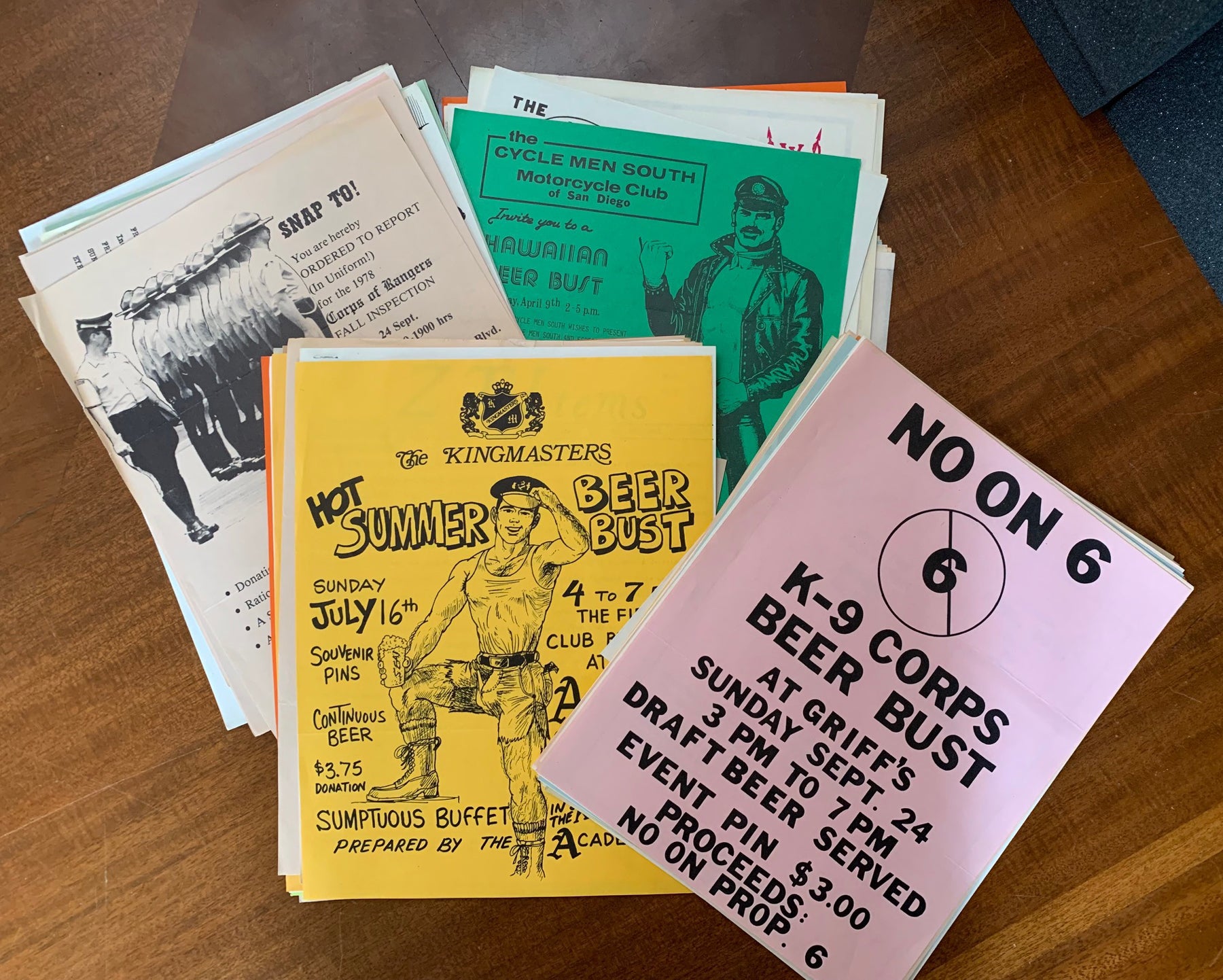

In 1978, L.A.’s gay motorcycle clubs raised money to defeat Proposition 6, which would have made it illegal for LGBTQ people to work in California’s public schools. And in the 1990s, the clubs were on the front lines of the AIDS epidemic, trying to promote safe sex, fight against the stigma of the disease and seeing their numbers dwindle as the death toll increased. Today, many of these clubs remain, and they’ve expanded to include a broad array of LGBTQ members.

An academic home for history through USC

Much of the motorcycle clubs’ history is preserved through the ONE Archives at USC. The archive features materials dating back to the 1940s, a vast collection that includes art, books, posters, documents, clothes, personal papers, movies, photos and film.

“It really links it back to the real human impact — you see the history of all the activism that has gotten us to where we are today,” said Hugh McHarg, associate dean for strategic initiatives at USC Libraries. “You see the contributions and the sacrifices.”

The history of the archives has gone through several transitions. ONE Inc. published ONE Magazine, a widely distributed LGBTQ publication, in the 1950s. A private collector of books and materials related to LGBTQ issues dating back to the 1940s then came together with ONE Inc. to establish One Institute.

By the 1990s, the personal collection merged with the institute. In the early 2000s, USC provided the ONE Archives with its current location at 909 W. Adams Blvd. in Los Angeles.

The collection’s size and diversity make it particularly appealing for interdisciplinary study, McHarg said. For example, its collection of six decades of activists’ posters tells the story of the gay rights movement while also providing a lens on the history of graphic design.

In recent years, ONE Archives has collaborated with Getty Pacific Standard Time for an exhibition about queer Latinx artists based in Los Angeles. That work was showcased in the ONE Gallery in West Hollywood as well as the MOCA Pacific Design Center.

Another partnership, this one with KCET-TV, focused on the Address Book, a resource for finding bars and other establishments friendly to the queer community that was similar to how the Green Book provided a guide for Black travelers.

But beyond being a place to learn, the archives are a place that builds community. With a team of 30 to 40 loyal volunteers, they put on events and serve as a welcoming place for people from all over the world.

“ONE isn’t an archive; it’s a cultural institution. People come here to find a great deal more than just historical documents,” Hawkins said.

History ready to be discovered

Because the archives aren’t fully digitized, searching through them in person offers the opportunity to find undiscovered stories.

For example, the motorcycle clubs’ collection has firsthand letters written by members, along with event flyers and hundreds of photos. The information has enough rich details to recreate the clubs’ heyday.

Because of the collection, we know that the Argonauts would hold annual Octoberfest parties. In 1981, $40 got you five meals, all the beer you could drink and a cabaret performance. And a flyer from a 1971 event shows the importance of secrecy back then. It describes an event’s location as “a private 53-acre ranch about an hour from L.A. It’s located in a hidden valley, so privacy is assured.”

We also know the clubs had rules about who could join: gay men 21 or older who were sponsored by at least one member in good standing and received affirmative votes from three-quarters of the members. They also had rules of conduct: Members could not drink beer during meetings until the club president called for an official “beer break.”

During the pandemic, when the archives closed to the public, curator Lexi Johnson led efforts to build a digital space that would showcase the collection. The archives’ Safer At Home virtual exhibit examines the concept of home and what safety means and looks like for LGBTQ populations, for example.

“We don’t want to lose that, so everyone at the archives is doing as much as they can,” McHarg said. “For people who can’t come out here and visit the collection, they use it to find meaningful stories here.”

The pandemic also gave the archives an opportunity to work with institutions outside of Los Angeles. For example, ONE Archives partnered with the Leslie-Lohman Museum of Art, a self-described “home for LGBTQ+ artists, scholars, activists and allies,” to create a monthly series called Remote Intimacies that brought performance art to people through their phone, computer or television.

As Los Angeles reopens and the ONE Archives once again opens its doors to the public, its organizers are excited to finally welcome the public back to their events.

Events at the archives are often followed by receptions that allow the audience members to mingle, talk to panelists and make new friends. Those spontaneous interactions only come from in-person events, and Johnson wants to bring them back.

“Zoom allowed us to still have a panel, but it didn’t allow us to have small breakout discussions with friends after the event like we normally would,” she said. ‘Those are spaces we are all hungry for.”