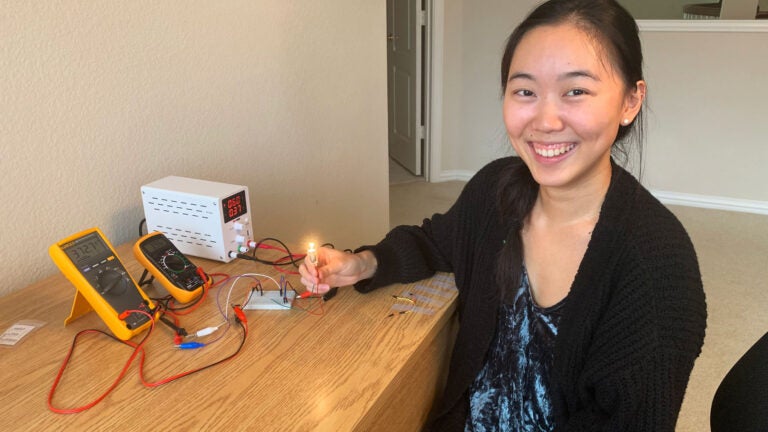

USC senior Elizabeth Zhou builds and tests a basic electrical circuit for an advanced physics course using equipment sent to her home in Dallas. (Photo/Courtesy of Elizabeth Zhou)

No lab, no problem: Students tackle science experiments at home after special deliveries

USC mailed more than 1,000 lab kits to its college students around the world so they could still do hands-on experiments while studying remotely during the COVID-19 pandemic.

When Elizabeth Zhou pulled the wires, alligator clips and other electrical parts from a package that showed up at her doorstep in Dallas, she felt a jolt of excitement tinged with apprehension.

The USC physics and computer science major had drawn countless diagrams of electrical circuits in her class notebook. But she had much less experience connecting wires, batteries and other gadgets in real life. After some fiddling and a few moments of frustration, she flipped a dial and a tiny lightbulb on the circuit glowed. Eureka!

Zhou also glowed — with pride at her newfound knowledge and abilities.

“Even if it’s a small circuit, it feels really gratifying to know that I made this circuit,” said Zhou, a senior at the USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences. “I saw there was some kind of bug or something wasn’t working right, and so I had to check over my own work and figure it out myself.”

That hands-on experience is precisely why her instructor, Jack Feinberg, devised science experiments all summer. When the COVID-19 outbreak kept more than 1,000 USC undergraduates enrolled in physics labs away from campus, he organized kits full of equipment to be shipped to their homes this fall instead.

The longtime professor of physics, astronomy and electrical engineering at USC Dornsife knows that often the best way to learn is to do. And he wasn’t about to let a global pandemic keep his students from that thrill of discovery.

“I want to give them a taste of what it’s like to be a real scientist. There’s a certain joy in doing something yourself,” he said. “It’s the difference between a racing car video game and driving a Formula 1 racing car on a track. There really is no comparison.”

Feinberg credits a bit of luck and some useful connections for the successful campaign to ensure physics students could still tinker, scrutinize and experiment this semester. But his colleagues say that Feinberg’s dogged determination deserves most of the praise.

“He definitely went beyond the call of duty,” said Stephan Haas, department chair and professor of physics and astronomy. “I think he also realized there was a dire need to do something. Just doing simulations or watching a video doesn’t make up for the experience and enthusiasm students can develop if they have some hardware in their hands.”

Hands-on learning continues at USC despite COVID-19 pandemic

Feinberg’s summerlong scramble to prepare for the fall semester began in the spring. He teaches a senior physics lab each year in which students use advanced equipment to perform experiments. When COVID-19 forced them online in March, he initially had them practice techniques using computer simulations.

But he quickly realized they would learn more if they could continue doing hands-on tests. He purchased, assembled and mailed a kit of components to each of his 11 students.

Atef Sheekhoon took the advanced experimental lab in the spring before he graduated with a bachelor’s degree in physics. He still has his collection of simple items from Feinberg, like a tuning fork and a Slinky, which he used to explore the properties of waves.

In one experiment, Sheekhoon held the ends of the Slinky and moved one end up and down. When he shortened the Slinky by grasping more coils in one hand, the frequency of the waves formed by the rippling toy changed.

“None of the experiments I did at home were things I hadn’t already learned about,” he said. “But I’d never done these simple experiments that could explain a certain phenomenon. Seeing that was beautiful.”

A monumental task: Shipping physics kits to more than 1,000 students’ homes

Before COVID-19 emerged, Feinberg had already agreed to gradually revamp USC’s undergraduate physics lab courses over the course of several years. By early June, however, he realized most classes would be held online this fall and pushed his effort to create new experiments into overdrive. It meant he had only a few months to design experiments and prepare hundreds of lab kits for five undergraduate courses taught by nine professors.

After he secured approval — and funding — from leaders at USC Dornsife, Feinberg hunted for simple experiments that could be done at home. He adapted some from the existing undergrad lab manual, developed by physics lab director Gökhan Esirgen. He called colleagues for suggestions. And he found others online, including many from a research paper titled “Ruler physics: Thirty-four demonstrations using a plastic ruler.”

Next, Feinberg grabbed equipment from his USC lab and hunkered down to perform physics experiments for 12 hours a day. “My home office looks like a tidal wave hit,” he said.

Some of the experiments proved too tricky, boring or impractical. Others needed expensive parts. But some worked out great, and he soon had a list of solid ideas.

Then he called Anton Skorucak.

A Trojan Family connection proves vital in mailing lab kits to students

Skorucak had earned his master’s degree in physics at USC in 1999, studying under Feinberg. They even launched a fiber optics startup together, but the dot-com bust derailed their entrepreneurial dreams. Skorucak went on to found xUmp (pronounced zump), an online science supply store.

When Feinberg asked him about putting together physics kits for USC students, Skorucak initially thought he meant for a class of 18 to 20 people.

“But then he sent an email saying, ‘By the way, I need these for at least 800 students,’” Skorucak said. “I said, ‘Uh, when do you need this by?’ In these COVID times, the supply chains are completely disrupted.”

Feinberg envisioned a medley of materials, from technical items like oscilloscopes with alligator test leads and digital voltmeters to everyday components like tape measures and bouncy balls. Skorucak called in every favor he could with his many overseas vendors.

“It was a little bit of twisting some people’s arms and a little bit of luck,” he said.

A container ship carrying many of the needed supplies cruised into the Port of Long Beach in mid-August. Skorucak assembled and shipped the kits in time for USC’s labs to start during the third week of the fall semester.

At last count, 1,053 shoebox-size parcels went out to students and teaching assistants across the country and beyond. Nearly 100 kits traveled abroad to places like China, Brazil, Vietnam, Costa Rica, Hong Kong, Canada and Singapore. For Skorucak, it was all worth it to ensure USC students have access to hands-on science.

“They kind of have that aha moment,” he said. “To me, when you see something happen right in front of your eyes and measure it and make sure what you’re seeing is correct, something clicks in your mind. You’re seeing nature firsthand, in a way. There’s nothing between you and this particular phenomenon. It’s pure truth.”

Physics students embrace hands-on learning at home

Aaron Wirthwein sees those same flashes of inspiration on his students’ faces. The third-year physics doctoral student is a teaching assistant for an introductory physics course for pre-med undergrads. He’s excited to see how they respond to the experiments.

“I think it’s really cool, especially coupled with the idea that it’s more of a playground and less of a to-do list you have to follow,” Wirthwein said. “The experiments are relatively simple, so the students have more of an opportunity to think for themselves.”

Zhou enjoys the troubleshooting she has to do when plans go awry in one of her experiments. She is taking Feinberg’s advanced lab this semester and hopes to pursue a doctorate in physics. After a friend told her about the kits Feinberg sent out spring semester, she was excited to try new experiments from home this fall.

“For those of us who want to continue to do hands-on work or applied physics, we’ll have to make that transition from theoretical proofs and diagrams we draw in our notebooks to actually implementing them and working with the materials,” she said. “It’s humbling to realize that even with basic circuits, I’m still building my intuition.”

The kits also have helped some students embrace their natural curiosity. Sheekhoon, for example, tested an experiment that wasn’t assigned in class.

“I remember seeing this one problem about measuring the speed of sound, and I tried to figure it out experimentally,” he said. “I used a tuning fork, a water bottle and a pipe — that was it. That’s how you learn. The more you have to use your brain, the more you learn.”