Earthquake Center interns leave lab behind, getting their hands on real faults

The students are spending the summer doing important research at the Southern California Earthquake Center, considered an international leader in earthquake forecasting

When stopping by the corner of Hollywood and Vine, many visitors marvel at the Capitol Records Building.

But earthquake scientists geek out on something else: the Hollywood fault.

Standing over the Hollywood star of a 1950s yodeler, USC Earth Sciences Professor James Dolan pointed out a cliff — a result of past rumblings — to interns from the Southern California Earthquake Center (SCEC) at USC.

It amazed 21-year-old Rafael Cervantes. He grew up in Los Angeles and had always heard about big faults — like the San Andreas — but never thought about the smaller ones that run through the region’s urban areas.

“That was pretty scary because it’s really highly populated and the amount of damage it could do,” said Cervantes, an SCEC intern who will be starting at the University of California, San Diego in the fall.

The eight-week summer intern program gives 22 students from across the U.S. the chance to do top-tier research with SCEC, considered an international leader in earthquake forecasting. It’s competitive: This year’s program had more than 250 applicants. The interns are paid a stipend of $5,000 for their work and given free housing at USC.

Sharing their work

During much of the program, they’re broken up in teams, spending their days in a lab making videos, testing earthquake scenarios or analyzing possible damage. It’s all to address a “grand challenge,” a real issue facing earthquake scientists. The interns’ work — whether it’s data crunched by a supercomputer or video simulation software — is presented to earthquake scientists at SCEC’s annual conference as research for the community to build on and use.

But for a couple of days last week, they got to ditch the computer screens for the real world. And what better place to do it.

We call California a natural laboratory because we have so many faults here.

Jozi Pearson

“We call California a natural laboratory because we have so many faults here,” said Jozi Pearson, SCEC’s intern supervisor.

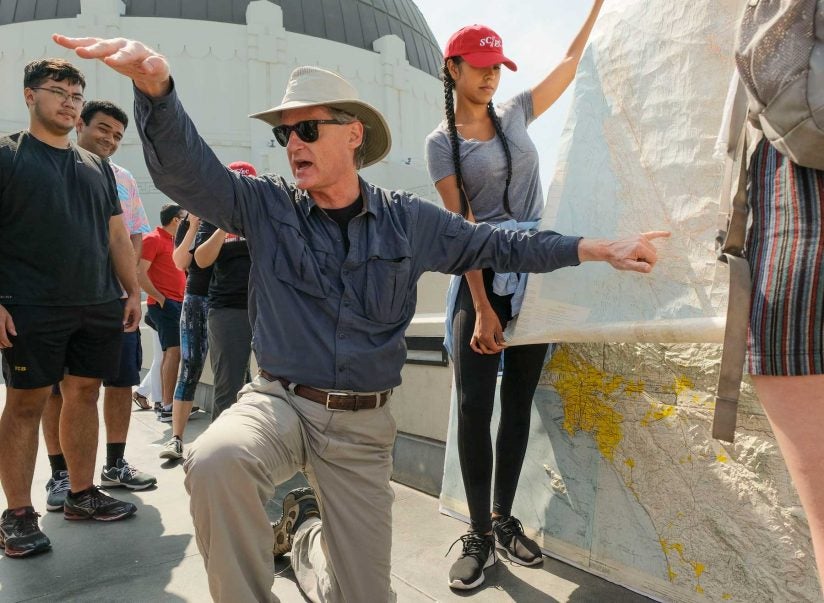

They started out at L.A.’s iconic Griffith Observatory. As tourists zipped by eager to grab pictures of the Hollywood sign and L.A. basin, SCEC interns tried to spot the Puente Hills blind thrust fault through some early morning haze.

Dolan likes to use the vantage point as a place to point out all the different regions — like fault areas or mountain ranges — they’ve only known from maps.

“On a clear day you can see where the bottom of the fault is, in Pasadena, and the top at USC,” Dolan said.

A few hours later, after a lunch break, they touched a fault. Yes, touched it.

Just outside the headquarters of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, students huddled near a creek. Dolan got out a shovel and pushed some soil aside and there it was: the Sierra Madre.

“It just looks like a crack with white rock on one side and brown rock on another,” he said.

Beyond L.A.’s urban geology, the students also got a glimpse at the mighty San Andreas, perhaps one of the most infamous faults in the country. They hopped on a bus and went to Palmdale, touring a portion of the 700-mile fault. Part of the fault is visible from the highway.

“Faults tend to be a dot on a map but they’re not. … They can be exceedingly large,” Dolan said.

‘Drop, cover and hold on’

While Californians grow up knowing to “drop, cover and hold on,” a third of the interns are from out of state, many never having experienced a quake.

Amelia Midgley, a student at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, read up on California’s tectonic history before she came. That made the reality of being in earthquake country a little nerve-wracking.

“To be honest, as a geologist from Massachusetts, I did come here a little worried,” she said. “There was a 3.3 earthquake yesterday just north of San Francisco.”

But even though she’s never felt an earthquake, she’s enamored by the science — especially the possibilities that forecasting brings.

“The more we learn about them, the more we can understand their complex processes,” she said. “I think the best thing is preventing or mitigating as much damages as we can because earthquakes cause a lot of damage, as we’ve seen before in in 1906 [San Francisco] or 1857 [Fort Tejon] earthquakes on the San Andreas fault.”

Dolan, who led the L.A. excursion, said he doesn’t mind playing earthquake tour guide.

“I like doing these field trips in the hopes that some of these interns will prove to be the next generation of really great earthquake scientists,” he said. “They’re not typically going out in the field and seeing these things. … There’s no substitute for someone saying ‘Right over is the east end of the 1971 earthquake rupture and that mountain to the west is the west end — and that distance is what a 6.7 earthquake rupture is’.”