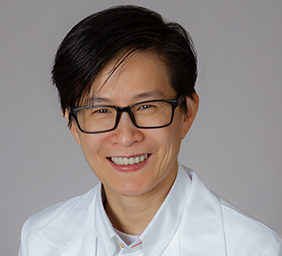

As the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus outbreak escalated into a pandemic, USC lung researcher Ya-Wen Chen expected to be spending a lot of time at home, sheltering in place.

“At the beginning of the quarantine, I was going to focus on writing grants,” said Chen, who joined USC as an assistant professor of medicine, and stem cell biology and regenerative medicine in 2019. Chen is also a member of the USC Hastings Center for Pulmonary Research, and the Eli and Edythe Broad Center for Regenerative Medicine and Stem Cell Research at USC. “I also wanted to spend time cleaning my house, cleaning my backyard, getting everything on track.”

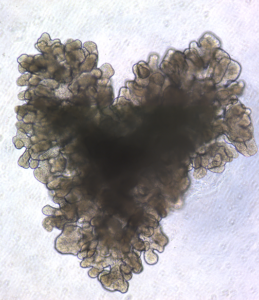

Instead, Chen realized that her laboratory possesses a key resource to advance the fight against COVID-19: mini human lungs grown from stem cells. These lab-grown lung structures, known as organoids, provide a safe way for scientists to test potential anti-viral treatments that might fight the SARS-CoV-2 virus that causes COVID-19.

While this is Chen’s first foray into coronavirus research, it is not her first quarantine. When SARS-CoV broke out in 2003, Chen was living in Taiwan, where she grew up.

She spent her childhood in a small rural village, playing in rice fields with her three siblings and more than 20 cousins. In high school, she had an inspiring teacher who encouraged her to pursue biology, and she began studying how serotonin controls blood sugar in crayfish.

“After I graduated, my teacher passed away while he was collecting samples for the class. He got hit by a car and fell off a cliff,” she said. “We were actually very close. He was the type that if he didn’t know the answer to a question, he would tell you that. And then once he had an answer, you would see him standing next to the door of the classroom, waiting to tell you. I was moved by his sincerity, and I knew a lot of students who became interested in biology because of him. For me, that’s the sign of a truly successful teacher—one who inspires students to love what he or she teaches.”

Chen went on to pursue a bachelor’s degree in biology at Tunghai University in Taiwan. The department focused heavily on ecology at the time, and her assignments included everything from collecting 30 different species of spiders to observing fireflies in the middle of the night.

Although insects are interesting, Chen had an even greater curiosity for medical research. She moved to the United States and earned a master’s degree in tumor biology from Georgetown University in 2007, and a PhD in molecular medicine from the University of Maryland, Baltimore, in 2012.

“Asian parents always like to encourage their kids to go to school,” she said, “but not my parents! I got a PhD not because I like to study. It’s just because the dream job I want to do, being a scientist, requires the degree.”

During her PhD studies, she began to explore skin regeneration and became fascinated by stem cells and regenerative medicine.

For her postdoctoral training, she joined the stem cell laboratory of Hans-Willem Snoeck at Columbia University, and developed human lung organoids. Less than a centimeter in diameter, these simplified mini organs recapitulate key aspects of human lung development, and can also become fibrotic or infected by viruses.

As a postdoctoral trainee, Chen also collaborated with a large research team to develop a technology to maintain badly damaged donor lungs outside of the body, and allow them to heal to the extent where they meet the criteria for transplantation into a patient.

In January 2019, Chen joined the faculty at USC and started her own laboratory.

“I’m gay, and to live comfortably, without worrying about being discriminated against, was an important factor for me in choosing where to start my faculty career,” she said. “USC is a prestigious school, and the Pulmonary Division and the Department of Stem Cell Biology and Regenerative Medicine have the culture of cultivating junior faculty and encouraging interdisciplinary collaborations. The idea of being able to pursue what I’m truly passionate and curious about made me decide to join USC.”

Chen’s lab uses human stem cells to study lung development, injury and disease. One of the lab’s major goals is to find a method for mass producing large numbers of identical lung organoids. These organoids could be used to screen thousands of potential drugs to treat pulmonary fibrosis, as well as several infectious diseases.

One of these diseases is COVID-19. The lab is working to develop an antiviral to prevent the SARS-CoV-2 virus from entering the cells that line the lungs, called the epithelium. Our lung epithelial cells contain a receptor called ACE2, along with an enzyme called TMPRSS2. The virus uses this enzyme as a key to “unlock” ACE2, which then becomes an entry point for invading and heavily infecting the lung cells. Chen’s team is using lung organoids to test whether an antibody can block the enzyme, locking out the virus.

To test another potential antiviral that might protect the lung cells involved in gas exchange from the SARS-CoV-2 virus, Chen is collaborating with Justin Ichida, who is the John Douglas French Alzheimer’s Foundation Associate Professor of Stem Cell Biology and Regenerative Medicine at USC. To support this research, the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine, CIRM, has awarded the team $150,000.

Other projects in the lab involve everything from growing blood vessels to support lung organoids, to regenerating the trachea and airway to help patients with genetic diseases such as congenital tracheal stenosis.

“For me,” said Chen, “I always want to fulfill my curiosity to find the answer.”