Astrid Heger, a professor at the Keck School of Medicine at USC, was looking for a way to teach empathy, kindness and caring that did not involve panels of talking heads or dreary online assignments. She was fed up with those. The answer, she discovered, was theatre.

“When people get up out of their chairs and are acting together, nobody in the audience is on their phones,” says Heger, a professor of clinical pediatrics, and the founder and executive director of the Violence Intervention Program at LAC+USC Medical Center. “They can see themselves in the situations being portrayed and you can have real learning. This way of learning should be driving us as a university.”

Four years ago, Heger had a dinner with Brent Blair, who directs the School’s Institute for Theatre & Social Change, that planted the seeds of a residency called ACT Together that debuted at two adult primary care clinics at LAC+USC in 2017. The staff of those clinics work with some of the nation’s most vulnerable patients, and often suffer from caretaker fatigue. The clinics see patients whose physical illnesses frequently coexist with mental illnesses and addictions, and poverty often complicates their ability to follow medical recommendations.

Josh Banerjee, who was then the medical director for the clinics, had a fellowship from the California Health Care Foundation that came with a charge to develop an innovative solution to a health care problem. Banerjee knew the problem he wanted to tackle: medical providers at the clinics feeling powerless, voiceless and burned out.

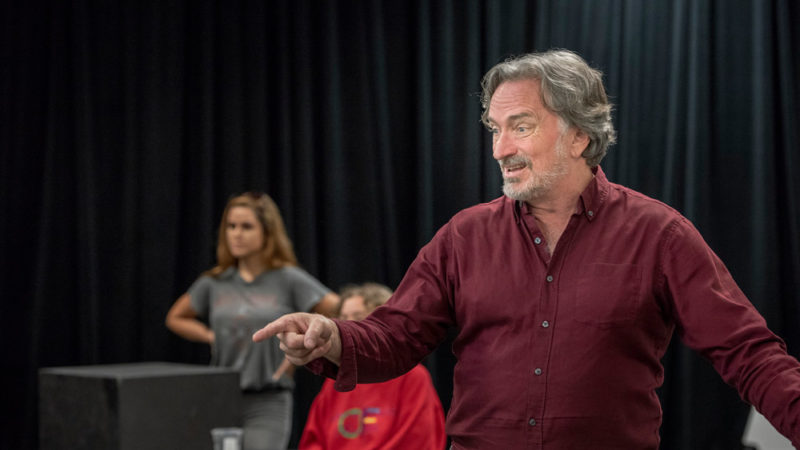

Blair, a professor of theatre practice, has spent his professional life using theatre to help marginal and oppressed communities find solutions to difficult problems. Heger introduced Banerjee to Blair, and then provided funding for the project.

Blair hired actors — some from marginalized communities — to play the roles of patients. Doctors, nurses, medical technicians and hospital social workers were recruited to work with the actors to develop six scenes that illustrated some of the tough situations the clinicians frequently face.

“We showed an ‘anti’ model of how things should not be done,” says Blair. “All the scenes were carefully designed and scripted for failure.”

One scene had a doctor recoiling in horror at the sight and smell of a patient’s badly infected leg wound. Another involved a woman who had suffered physical abuse being unable to show her scars to medical staffers because her abuser remained in the examining room. Another detailed how financial paperwork runarounds caused a patient to miss his appointment.

The scenes were presented differently by which the audience members, the clinic employees, were asked to step in and replace the actors and medical personnel originally doing the scenes. They were told to use their experience and wisdom to bring about better outcomes. The original actors and medical personnel performed the same scene repeatedly, giving the opportunity for several audience members to try different solutions.

“When doctors, nurses and medical staff get up and act instead of talk, they have body memory that lasts into their practice,” says Blair. The result, he says, is that employees feel seen and heard. “They feel better when they are on the medical floor the next day.”

Four times a year, Los Angeles County Department of Health Services (DHS) — which operates the clinics — measures employee engagement with surveys and Banerjee knew the clinics’ mid-range scores could and should be better. They had tried retreats, team building exercises and public recognition for staff members, all without much success.

The average for positive employee engagement for all DHS units was 3.69 out of a perfect score of 5. The score for the clinics Banerjee oversaw was 3.64. It’s difficult to raise scores by even one-tenth of a point, and Banerjee had an ambitious goal to raise the number to 3.75 during the six months the ACT Together program ran. Impressively, the clinics’ score went up to 3.81 during that time.

Survey questions specifically about ACT Together revealed approval ratings of 95 percent.

Banerjee gives credit to Heger’s support, and to Blair’s skill as a director.

“Brent always says that at its heart, theatre arts is play. You can’t force people to play, but you can invite them to play, and that’s what Brent does,” observes Banerjee. “His years of experience of speaking to people who are voiceless really shows in how he facilitates the sessions. He explains what everyone is doing, and he asks, not commands. Sometimes, he’ll narrate the scene as it’s going on, like a voice-over, and say something like ‘Poor Toni is struggling up here. Who can help?’ And then people step up.”

Blair says that even when there is no intervention that neatly solves the problem in a scene, the audience has changed from being passive to feeling active, useful and engaged.

The residencies were done six times in 2017 and 2018, and begin this fall. Blair and Banerjee have done presentations on the project for the California Health Care Foundation and LAC+USC, and are planning to co-author a medical journal article about it.

“ACT Together is important because people find purpose in their work when they feel they are making an impact,” says Banerjee. He is now the associate medical director for transitions of care at LAC+USC, and he and Blair are in discussions about expanding the program across the DHS. “This program can work for anyone, anywhere,” he says. “It’s the single most joyful project I’ve been involved with in my career as it gives front line staff voices and power. It’s democratizing health care, which is super unusual.

“Using theatre proved to be far more effective than traditional seated lectures or conferences.”

This story appeared in the 2019-20 Callboard magazine.