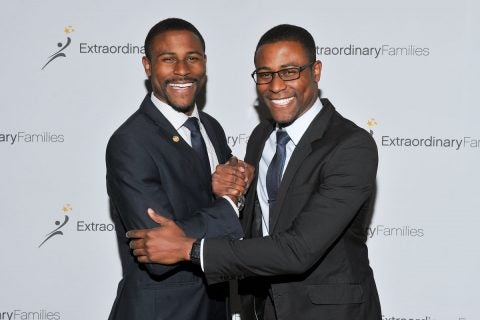

USC alumnus Demontea Thompson grew up in kinship care and is now an advocate for foster youth. (USC Photo/Eric Lindberg)

Former foster child, a USC alumnus, fights for foster youth

Demontea Thompson uses his USC master’s degree in education to advocate for children who face similar struggles in the foster care system

At age 26, Demontea Thompson looks back and knows he beat the odds.

Thompson was taken from his parents and placed in foster care as a child in Compton. While others around him chose gangs and drugs, he chose education. But he didn’t do it alone. Through it all, he relied on the support and guidance of a few key people.

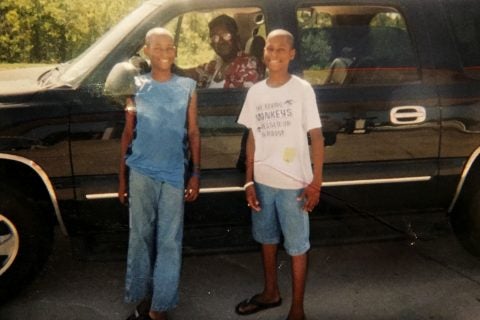

People like his twin brother, Demontray, a constant companion from the moment they entered the world together. His great-uncle Lorenzo and great-aunt Verna Mae, who took in the two boys when their parents couldn’t care for them. The mentors in college who encouraged him to keep pushing forward even when it felt like he didn’t belong, helping him earn a degree from California State University, Northridge, and then another from USC.

These people played pivotal roles, inspiring Thompson to give back by advocating for others in foster care — a drive that turned into his career.

Now as a resident director of housing at California State University, Los Angeles, Thompson creates services for former foster youth and oversees other peer support initiatives. He volunteers with Echoes of Hope, a nonprofit that supports foster children and other vulnerable young people.

He and his twin brother are also developing their own nonprofit called TwInspire to advocate for and educate young adults through workshops on financial literacy, academic success and other life skills. And Thompson envisions earning a PhD in a subject like higher education or social work to help him continue tackling issues facing foster youth.

It’s his way of honoring the sacrifices and support of those who helped him overcome countless hardships on his path to success.

“I really found my family. They’ve given me the best example of who I need to be and how I can serve others,” Thompson said. “I want to connect people to resources just like they did for me. And if I don’t feel like I’m heading in that direction, I check myself. I’m always reflecting on my purpose and my journey.”

A new family emerges after a tough start

Thompson was born into difficult circumstances. His parents struggled with substance abuse and poverty. As an infant, he was placed into foster care. So were his five brothers and six sisters.

He was fortunate to remain with his twin brother. They got another break when their great-uncle and great-aunt took on the responsibility of raising them. Their great-uncle worked in construction, and he emphasized the value of education and hard work.

“Sometimes the streets would tell us something different, you know — take what you need or do what you gotta do,” Thompson said. “But our uncle helped us develop certain life skills. He taught us how to build homes, install floors and windows, instead of running around in the streets.”

Their great-aunt died when Thompson and his brother were 12, adding another complication. Now they had to grow up without a maternal figure during their difficult teen years.

“That was hard because we didn’t have anyone to talk to about things like, hey, I’m in love,” he said. “Instead, it was, ‘This is how you use a sledgehammer.’”

School becomes a sanctuary for future Trojan

Education became their main source of stability, along with the strict guidelines of their great-uncle. He wanted them home right away after school to do their homework and help him with one project or another.

That formula kept them on the right track throughout high school, but as they approached graduation, the next step was fuzzy. Then a visitor came to their school. Sean James, who now runs a college access program at California State University, Dominguez Hills, told them about his experiences at a four-year university and encouraged them to apply.

“I was thinking, this guy is cool — a black dude who kind of looks like someone I would know, and he’s in college?” Thompson said. “That’s dope!”

Higher education hadn’t felt like an option for the twins. They had no college fund. Nobody from their family had completed a university degree. But they decided to take a shot and enrolled together at California State University, Northridge, with support from a program for low-income and educationally disadvantaged students and another initiative for former foster youth.

They struggled to adjust to the rigor of college classes. But the twins slowly figured out the right study habits and began to excel in the classroom.

Then came another setback: Their great-uncle died.

They had been pushing themselves to succeed for him, Thompson said. Now they had to succeed for themselves. So they pressed onward, graduating at the top of their class. Thompson earned his degree in management; his brother majored in finance.

Although he had initially planned on a career in business, Thompson took another path thanks to two staff members at the university’s student union: Debra Hammond and Sharon Kinard. They had become mentors and mother figures to the twins during their undergraduate years, inspiring Thompson to pursue a graduate degree in education so he could find a similar role helping students.

USC scholarships pave the way for foster youth advocate

The master’s program in postsecondary administration and student affairs at the USC Rossier School of Education was a natural choice, but Thompson had used up all the state and federal funding for college he could receive as a former foster youth. He applied to USC anyway, expecting to have to take out substantial loans.

When he received his acceptance letter, however, he found out he had received the school’s Dean’s Scholarship and support from the Norman Topping Student Aid Fund, covering a significant chunk of tuition.

Then after his first year, he learned about Town & Gown of USC, the university’s oldest women’s organization. He promptly applied for and received one of the 150 merit-based scholarships it awards each year. More importantly, leaders at the nonprofit began connecting Thompson with people who shared his goal of supporting foster youth in higher education.

All of my interests in finding family, in finding that social capital to tap into had just been opened to me with the Town & Gown scholarship.

Demontea Thompson

“The doors were just opening left and right,” he said. “All of my interests in finding family, in finding that social capital to tap into had just been opened to me with the Town & Gown scholarship.”

He felt privileged but also conflicted, knowing that others were facing similar struggles and didn’t know about scholarships and other resources at USC. So when he shared the news on Facebook that he had received financial support, he also offered to help others apply to the Town & Gown program. A friend he knew from high school ended up winning a scholarship after asking him for advice.

“This scholarship is a possibility for those who otherwise would take another route that is unaligned with their purpose,” he said. “Financial burdens can make it hard to see the future, to have hope. Having the support of Town & Gown and the ladies there, who are so nice and connect you with so many resources, is amazing.”

USC alumnus finds his calling in advocating for foster youth

Thompson finished his USC master’s degree in 2017, writing his thesis on challenges and achievements of foster youth in graduate school. He was invited to present his findings at a conference in Bermuda and led a roundtable discussion on related topics in Ireland this year.

He still sees his brother regularly, and Thompson returns to USC often to meet with Town & Gown scholarship recipients and share his story.

He also envisions updating a book he wrote at age 19 on his path out of foster care, titled Raised from Scratch. The original version ends when he makes it to college, and he has plenty of advice to share from his journey since then.

He hopes it will inspire other foster youth to follow in his footsteps. They can be confident he’ll be waiting with a helping hand to guide them along the way.