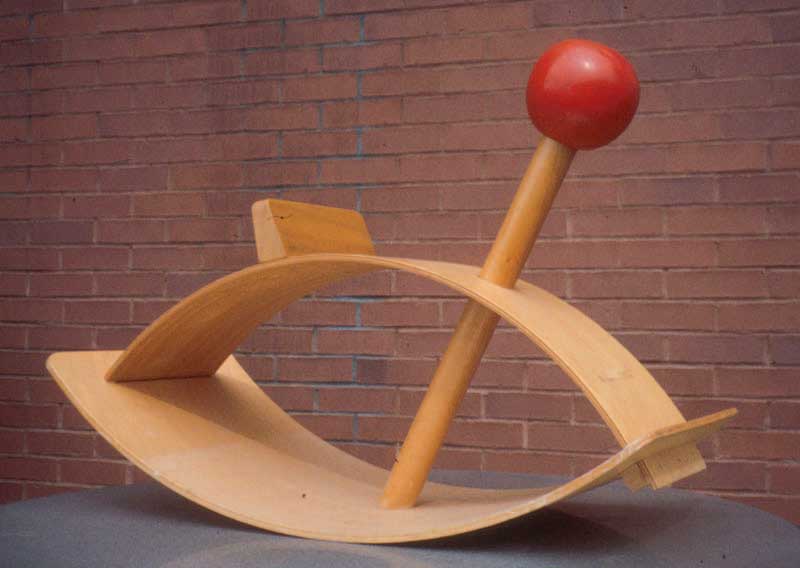

How design shapes play, learning and childhood itself was examined in a USC Dornsife course. (Illustration/Courtesy of Amy Ogata)

Pink for boys and blue for girls: the colorful history of things designed for kids

Whether it’s clothes, toys, books or schools, the designs tell students a lot about marketing and childhood

Walk into any American children’s clothing or toy store and look around. Almost blinded by pinkness? Then you know you’re in the girls’ section. The color is now indelibly associated in our minds with everything “girly.”

But that wasn’t always the case: Once upon a time, pink was the boys’ color, according to Amy Ogata, chair and professor of art history at the USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences.

“Pink was strong. It was understood as a forceful, assertive color,” Ogata said. “Blue, on the other hand, was considered to be flattering, a color of youthful beauty.”

That changed dramatically after World War II, as corporate marketers promoted color-based distinction between boys’ and girls’ clothing. The motivation? It prevents parents from handing down clothes between siblings of different sexes, Ogata said, so children’s clothing designers, manufacturers and retailers could increase profits.

That’s just one of the fascinating insights students learned during Ogata’s freshman course, “Designing Things for Kids.” The General Education Seminar course explored the history of objects designed for children — whether it’s clothes, furniture, toys, games, books or schools — and invites students to think about marketing and consumption.

Ogata encourages students to go beyond the universal experience of childhood to ask, “Why did it look this way? Why do Lego bricks or Barbies look the way they do? Why do some parents prefer wood toys over plastic ones?”

Childhood as a modern invention

The course was inspired by her book on the material culture of childhood, Designing the Creative Child: Playthings and Places in Midcentury America (University of Minnesota Press, 2013).

In it, Ogata says leading scholars have argued that childhood did not exist as a concept before the dawn of the modern era, with children represented as mini-adults before the 17th century. This controversial idea — that childhood is a modern invention — has been disputed by those who stress that medieval and early modern parents also showed great love and care for their children.

Ogata’s initial interest in the subject also sprang from the fact she’d just had a baby.

“I was suddenly confronted with this material world I was told I needed,” she said, one in which children’s goods stand separate from those of adults.

This separation can clearly be seen in furniture design, from the adoption of the high chair in the mid-19th century to the transformation of children’s beds, from baskets to elaborate rocking cradles to beds resembling race cars. All, Ogata said, reveal a lot about how we envision childhood.

What toys tell us

“Play is … acknowledged as universal, but toys are understood as cultural,” Ogata said. “We can read our own values in the things we give children to entertain themselves.”

A clear illustration of this is the debate over the relative merits of abstract wooden toys — often considered inherently more valuable and wholesome — versus so-called “realistic” plastic and metal playthings.

Proponents of the latter argue that realistic toys help ground children in the everyday culture of reality while abstract toys are the parents’ choice, Ogata said. Those championing the benefits of wooden toys argue that abstract design encourages the development of the child’s imagination — a rare and precious commodity they believe is worth cultivating and protecting.

Should innocence be preserved?

Students also explored the changes in school design, from postwar U.S. schools, designed to be reassuringly home-like, with curtains and hearths, to Germany’s turn-of-the-century open-air waldschulen, a device to combat tuberculosis. Their popularity encouraged the educational theory that children should be in nature, to preserve both their health and their innocence by providing a different life experience from adults.

This question of innocence is one that Ogata said lies at the heart of the course.

In what way do we want innocence as an expectation of childhood?

Amy Ogata

“In what way do we want innocence as an expectation of childhood?” she said. “What do we mean by it, do we want to preserve it?”

Students’ thinking shifts during the course, she said, from initially championing children’s innocence to questioning whether imposing innocence on children is inhibiting rather than empowering.

Changing ideas of childhood

While ideas about childhood may evolve over time, Ogata noted that one factor remains constant: Childhood experience through the centuries has always been mediated by class, race, gender and especially wealth.

“A wealthy child in 1800 has a certain kind of costume, certain kinds of toys, a certain kind of day,” she said. “If you’re a working-class kid, you’re working. You don’t have special clothes or toys.”

What about American childhood in the 21st century? Ogata said parents view it as a crucial moment.

“I think Americans are now fixated on training children so they can perform in a changing economy,” she said.

Ogata hopes that one takeaway for students is the understanding that childhood is not a neutral term, that they can understand the ways in which it’s been created and how that changes over time.

“Childhood is not something timeless; it’s not something neutral. It is something constructed. It’s different in the 18th century than it is in the 21st century,” Ogata said. “I hope my students understand that the childhoods that they may have lived were shaped in a very specific way, for very specific reasons.”