Family secrets and white-collar crime uncovered by USC historian

Alice Echols peels away the layers of a hidden history, exposing Depression-era financial corruption in the process

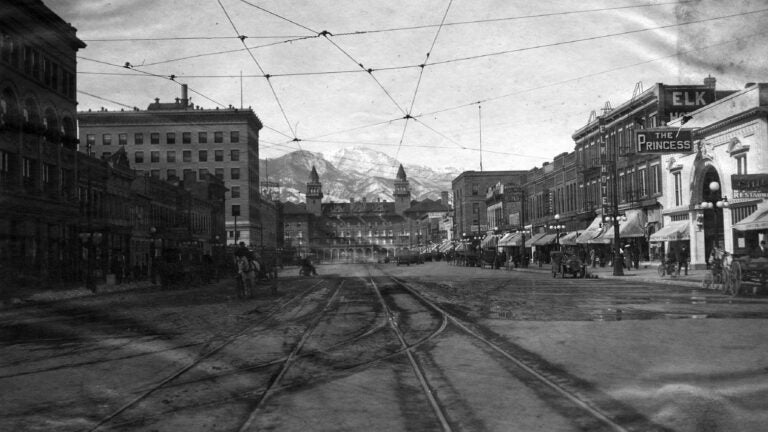

One evening years ago, Alice Echols got some unexpected — and shocking — news from her father: Her maternal grandfather, Walter Davis, had been a notorious white-collar criminal. The owner of the biggest building and loan association in Colorado Springs, Colo., Davis went on the lam in 1932 before authorities discovered his business was in the red an astounding $1.25 million — nearly $22 million by today’s standards.

Echols, professor of history and gender studies at the USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences, spent 10 years uncovering details of the scandal through an archive of family correspondence, photographs, a 200-page FBI file and a transcript of subpoenaed telegrams that passed between her grandparents. She also reviewed conversations with her elderly mother and research in libraries and archives across America.

The Depression-era failure of the building and loan industry, once a key component of America’s financial landscape, unfolds in Shortfall: Family Secrets, Financial Collapse, and a Hidden History of American Banking (New Press, 2017).

In the book, Echols uncovers the malfeasance that the building and loan industry covered up. She also reveals that the supposed virtues of Main Street lending — its intimacy and small scale — were no guarantees against fraud.

What inspired you to spend 10 years researching and writing this book?

Well, the family story is nothing if not dramatic: There are thwarted kidnappings, marital infidelity, financial ruin, desperate depositors and suicide. But exciting as all of that is, the fact of the matter is, that’s not enough to sustain an entire book. My task was to figure what my grandparents’ story could tell me about how capitalism operated on the ground, about what homeownership meant to my grandfather’s white working-class depositors.

How was it to discover this hidden family history after all those years?

Well, once I got over my annoyance at having been kept in the dark about my grandfather — I was middle-aged when I learned of him — it was kind of thrilling to learn that someone in my seemingly normal family had been anything other than respectable. This isn’t to say that I in any way condoned what he did, of course.

To what extent was this research a political history as well a personal one?

The defrauded depositors organized politically, and I found the way they mobilized fascinating. The leadership of the depositors’ group was active in a taxpayers’ association. Tax limitation groups, committed to cutting taxes and shrinking government, mushroomed in the early years of the Depression. They won support by attacking bureaucrats as well as those “shovel leaners” and slackers on government relief, and in ways that anticipate the rhetoric and reasoning of the Tea Party. Indeed, the leader of this group would go on to become one of the first supporters of Barry Goldwater’s 1964 presidential run. And Goldwater, when it came to social welfare programs, was anti-statist. I became fascinated by this little brown mouse of American conservatism, which has become the face of the Republican Party, and by its appeal to some white working-class Americans.

Your book brings up the idea of America’s tendency toward “cultural forgetting of bad capitalism.” What do you mean by this?

The book is a cautionary tale about the perils of forgetting those episodes when capitalism runs amok. In the 1980s, when the savings and loan industry was failing, the Reagan administration presented the regulations of that industry, which had been enacted during the Depression, as antiquated and unnecessary. Had opponents of deregulation been able to say, “These regulations were put into place in part because of fraud,” not just because of the Depression, perhaps the deregulation of the S&L industry might have evolved less recklessly, and perhaps the taxpayers would not have been left holding the $150 billion bill for its bailout.

It really is uncanny how we seem unable to reckon with our past.