U.S donations to the United Nations Population Fund previously helped provide access to health care and family planning around the world. Here, a doctor in Mongolia explains contraceptives. (Photo/Andrew Cullen, UNFPA)

USC experts foresee dire consequences of possible cuts in health funding

If implemented, the administration’s policies could threaten lives and diminish progress made around the world

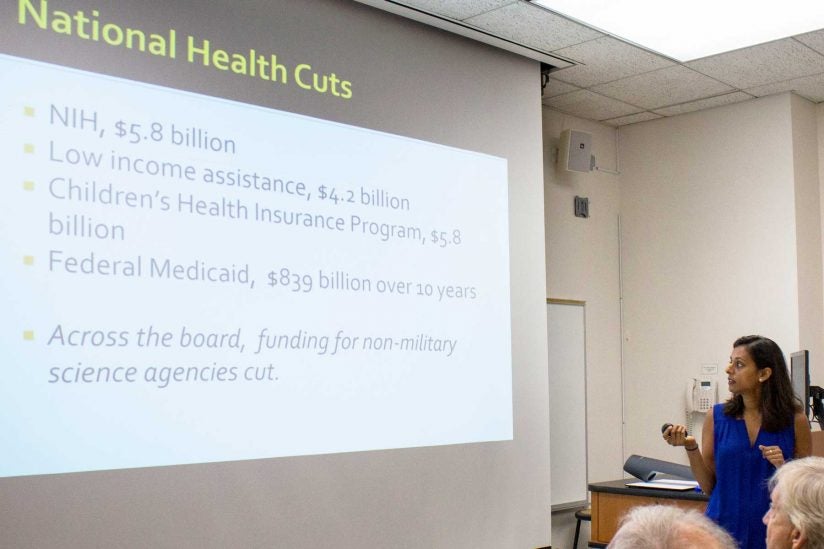

As President Donald Trump looks to slash global health funding, experts at a USC Law & Global Health Collaboration meeting warned of potential life-threatening consequences.

Parveen Parmar, chief of the Division of International Emergency Medicine at Keck Medical Center of USC, and a cross-section of USC faculty, presented evidence and preliminary reflections on how the administration’s policy changes could impact health in the U.S. and around the world.

A blow to health

The United States is the largest global health donor in the world.

“Now, some people will say, ‘Well, gosh — why is the United States donating so much?’ Well, actually, it’s less than 1 percent of our [gross domestic product],” Parmar said. “And if you look at some European nations, they are actually donating much higher portions of their GDP.”

But the president wants to significantly diminish international aid spending.

Family planning is particularly vulnerable.

“The Trump administration’s goal appears to be to have zero funding for all things related to family planning,” Parmar said, citing a Guttmacher Institute analysis that forecast what decreased U.S. assistance could cause: more unintended pregnancies, more abortions and more maternal deaths.

Compounding these prospects is a policy known as the Global Gag Rule, which the Trump administration not only reinstated, but expanded. Organizations now perceived to be providing abortion services, counseling or referrals will be ineligible for any U.S. financial assistance. In under-resourced communities, this could cripple already meager reproductive health services and other life-saving provisions, like vaccinations and HIV/AIDS treatments.

Indirect effects

Beyond the reduced dollar figures and potential fatalities, Parmar said she fears Trump’s policies will have an impact on climate change, immigration and civil rights in less measurable, less immediately obvious ways.

From the June 1 U.S. withdrawal from the Paris Climate Accords to the administration’s anti-Muslim rhetoric, Parmar provided examples of how Trump may be negatively impacting people’s health and well-being.

Reduced utilization of health services now is just the tip of the iceberg.

Parveen Parmar

Increased immigration raids, the “Muslim ban” and reversal of Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals — DACA — are already jeopardizing people’s lives and health, she said.

“I am a physician here at L.A. County and before we even had the numbers to prove it, we knew that people were not coming to see us,” she said, referring to undocumented immigrants. “And if they came to see us, they were afraid to see us.”

Patients who fear revealing their immigration status might delay seeking medical care — and this delay could lead to further complications — or death.

“Reduced utilization of health services now is just the tip of the iceberg,” she said. “And the mental health impact of these policies is unknown.”

Moving forward

Parmar called for researchers and academics to consider the ways in which Trump’s policies will impact the populations they serve, and the need for increased multidisciplinary collaboration. Advocacy, too, remains a potentially helpful domain for student and faculty engagement.

“One of the things I’m interested in is talking about the role of academics in advocacy, and how we maintain our objectivity while maintaining allegiance to facts in what has largely become a post-truth world,” she said.

After Parmar spoke, Sofia Gruskin, director of the Program on Global Health & Human Rights at the USC Institute for Global Health, facilitated discussion among USC faculty, staff and student attendees.

“This is the beginning of a multidisciplinary dialogue that can help set an important research agenda for USC,” Gruskin said.

An ongoing conversation

Gruskin co-leads the USC Law & Global Health Collaboration with University Professor Alexander Capron and Charles Kaplan, research professor and associate dean of research at the USC Suzanne Dworak-Peck School of Social Work. In its second year, the group is focusing its 2017-18 seminar series on the administration’s effect on law and global health. Last year’s events largely focused on issues at the intersection of health and law for transgender individuals.

The next seminar on Oct. 10 will examine media censorship, fake news and its implications for law and health.