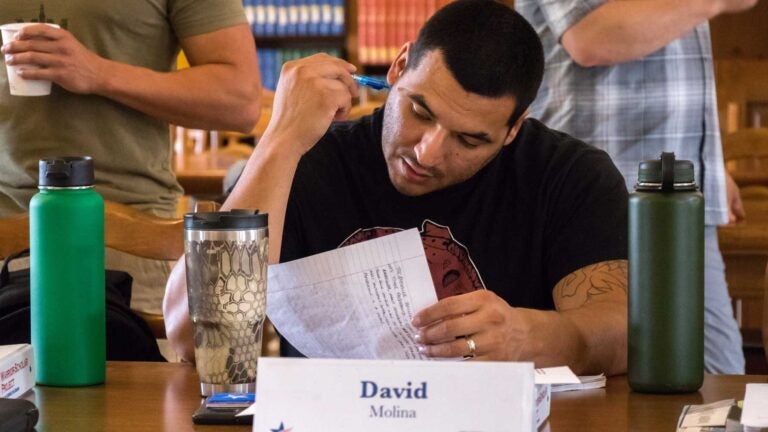

David Molina grew up near USC and later went on to join the Marines. (Photo/Victor Zaragoza III)

Warrior-Scholar Project guides Marine — a USC DPS officer — to success in school

The weeklong bootcamp prepares vets for an academically rigorous environment, and USC is the only California school that participates

David Molina sat on a couch hunched over his laptop in USC’s Veterans Resource Center, finishing up his essay analyzing Alexis de Tocqueville’s Democracy in America.

It’s 7:30 p.m. on a Tuesday night and the essay is due in two hours.

“It has to do with the political consequences of the social states of Anglo-Americans,” said Molina, 28. “I feel like I’m finished. I just have to revise.”

Molina thought the 19th-century scholar’s views on the U.S. still felt relevant today.

“Overall, the pursuit of happiness is more important than being free, so to say,” Molina explained. “The only person who was truly free was the king.”

He found it kind of ironic to be discussing freedom in this way, because he’s so used to talking about protecting it.

Molina is a Marine, who served three years until 2011 including a deployment to Iraq, and is at USC participating in the Warrior-Scholar Project — a national program that partners with top-tier universities for a weeklong bootcamp, preparing veterans for an academically rigorous environment. USC is the only school in California that participates.

The free program is focused on writing, reading and study skills, along with lectures from USC faculty, who volunteer to teach. The hope is participants leave with a renewed confidence about applying to a top-ranked school. Only 1 percent of veterans attend top 20 universities, the organization reports. According to the American Council on Education, the majority of veterans — 61 percent — attend two-year community colleges or for-profit schools.

For veterans, the transition to higher education can be stressful. Most student veterans are older, between 24 and 40, and haven’t been in a traditional classroom in years, even decades. During Tuesday night’s study hall, one veteran joked the workload was making him want to re-enlist, but after some help and advice from a staffer, he said he changed his mind.

USC student for a week

For this one week, Molina was a USC student. He talked with professors such as Jody Armour, ate meals in the dining hall and slept at Cardinal Gardens alongside his program pals. The days are long, from 7 a.m. to 10 p.m., and many of the 20 participants study into the early hours — just like finals week.

It felt a little weird to Molina, who was seeing USC from a totally different perspective. On a usual weekday, he’s a USC Department of Public Safety officer, working in campus surveillance. At night, he goes home to his wife and 2-year-old son in South L.A.

“It’s interesting to be on the other side of the coin,” he said. “I’m not the one tending to the grass. I’m the one playing on it. It’s tough, but I like it.”

His USC co-workers were supportive of him doing the program and pursuing his dream of higher education, he said.

And they had their eyes on him.

A couple days into the boot camp, he got a text from a co-worker. Molina laughs as he shows a grainy black-and-white image of him looking serious while eating at the Ronald Tutor Campus Center with a teasing text: “Why you mad, bro?”

Because of his job

If it weren’t for his job, he might not be considering USC. Molina attended the Foshay Learning Center — part of the USC Family of Schools — before graduating from Los Angeles High School, and grew up in an old Victorian house off 25th and Vermont avenues, and never saw a top-ranked school as an option.

Fellow DPS Officer Santiago Gil nudged Molina to see it as a possibility. Gil, a veteran who went through Warrior-Scholar Project last year and is now a USC student, pressed Molina to check out the Veteran’s Resource Center and a transfer luncheon for vets.

Ever since, Molina has had his eye on USC – making sure his credits will transfer from East Los Angeles College and Los Angeles Trade-Technical College. He’s a first-generation college student, the son of Mexican immigrants — his dad is a handyman, his mom does odd jobs.

Now Molina has his sights on geological sciences.

“I like rocks and stuff,” he said. “I really like minerals and how they’re developed deep down in the earth.”

Gil, 34, knows how hard it is to make college work at this point in their lives. He has a wife and two kids in Corona and still works full-time for DPS. During busy weeks, he sometimes sleeps in his car so he won’t fall back on his studies.

But he says seeing Molina’s motivation motivates him, too.

“It makes me finish my goals, knowing there’s other veterans that are like ‘If Gil can do it, I can do it, too,” said Gil, who is assisting this summer’s bootcamp.

Making changes

A few days in, Molina was already seeing the program make a change in him. He was making daily to-do lists and managing a “master calendar” — a time-management trick he learned in one of the assigned books.

Although they were given three hours to write that essay, he finished most of it the night before, in an hour and a half.

“I was done and I felt great about it. I wasn’t overwhelmed,” he said. “I love what I’m getting out of this. These are skills I didn’t have.”

Later on Tuesday night, he opened up the Common App, the multi-college application program used by USC and other universities. Normally the thought of tackling it produces anxiety, but this time he looked at the blank space where a 650-word essay would go and thought: “I got this.”