Alumna works on navigational instruments that boost space flight

Chemist who holds 14 U.S. patents and two trade secrets helps develop key components for gyroscopes and Mars rovers

Mirrors and mechanisms in a ring laser gyroscope — key elements for an aircraft’s navigation — played a role in the career of chemist Christine Geosling PhD ’77.

When Geosling joined the global aerospace and defense firm Northrop Grumman, she was part of an interdisciplinary team of scientists developing the gyroscope. The instrument makes up a vital element of the navigation system for aircraft, ships and spacecraft, helping them with pointing, tracking and flight control.

“As a chemist, I was working primarily with the mirrors of the laser, and this being a project under development, it needed a lot of improvement to meet the performance goals that we had for it,” Geosling said.

As the team’s sole chemist, her main focus was to improve one of the mechanisms that was destroying the mirrors in the unit. And as it turned out, what was killing the mirrors was a chemical reaction.

“I was able to identify it, do the experiments to verify it and suggest a solution,” Geosling said.

That challenge — and her subsequent work for Northrop Grumman on the laser gyroscope and fiber optic gyroscope — earned Geosling a prestigious 2013 Resnik Challenger Medal. The award, presented by the Society of Women Engineers, honors visionary contributions to space exploration.

“It’s a great honor and it also reflects well on Northrop Grumman and the work we do and the quality of the products we produce,” Geosling said. “We’re very proud of the fact that we can produce something that can survive for 10 years-plus on Mars and in space. The fact that I can receive an award for essentially underscoring the fact that we succeed and do well in that mission is very satisfying.”

The pull of chemistry

Geosling, who holds 14 U.S. patents and two trade secrets, said she was drawn to science since she was young. She was in high school when she became partial to chemistry.

Chemistry had a special appeal. Being able to see, feel, touch, hear the results of your work — I guess it was just what I gravitated toward.

Christine Geosling

“I enjoyed physics, too, but chemistry had a special appeal. Being able to see, feel, touch, hear the results of your work — chemical reactions, changing colors, explosions even — I guess it was just what I gravitated toward. Then, when I went to college, I just had no question I was going to declare that as a major.”

Geosling earned her bachelor’s degree in chemistry from Northwestern University and then set her sights on moving from the Midwest to Southern California for her doctoral degree.

“I was offered a teaching assistantship at USC and visited the campus. I was struck by how pretty it was,” she recalled. “The faculty were all very enthusiastic and encouraging. So that sold me.”

Career trajectory rises

Under the guidance of the late chemistry professor Arthur Adamson, Geosling’s dissertation research focused on measuring the photochromic reaction rates and thermal decay rates of metal dithizonates. She earned her PhD in chemistry in 1977.

She said her experiences at USC are some of her best memories.

“In PhD programs, you become part of a very close knit group with the professors and your other grad school colleagues and post-docs. We did a lot of things together socially.” That included going to dinner, out for drinks and, of course, to many Trojan football games.

Her interactions with faculty also had a profound impact on the trajectory of her career. In addition to Adamson, she counts Larry Singer and David Dows among her faculty mentors in the department. Adamson, however, was paramount in helping her to secure her first job after earning her doctorate.

Adamson helped her to connect with the Laser Physics Branch at the U.S. Naval Research Laboratory in Washington, D.C., where the work aligned with her expertise in photochromic materials, which change color depending on light intensity. She worked there for eight years before coming back out west to work for Litton Industries, which was later acquired by Northrop Grumman.

Geosling recently returned to USC Dornsife to share her professional insights with chemistry majors during an alumni career panel on the University Park Campus. She said students were most interested in how to plot their career course. Since that must be personalized for an individual’s desired career path, Geosling directed students to follow their passion.

“Basically, if you enjoy what you’re doing, you’re probably not too far off,” she said. “Also, a lot of times careers take strange turns depending on what doors open. You have to pay attention to those opportunities.”

Mission to Mars

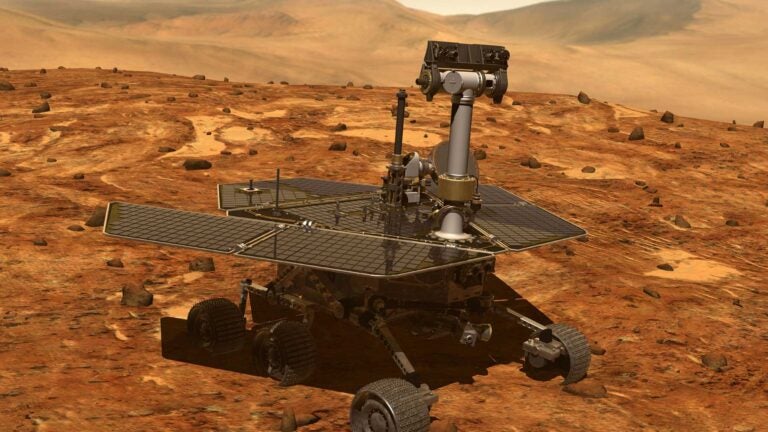

Geosling currently works as an engineering program manager at Northrop Grumman for the LN-200 line of inertial measurement units. These provide critical information for NASA’s Mars Rovers, such as the degree of tilt the rovers experience while navigating, which allows them to make precise movements to make observations and to help position their antennae to transmit data and photos back to Earth.

“I’m probably one of the few that can say, ‘I have touched something that’s now on Mars,’” Geosling said.

She quipped that any actual fingerprints have certainly been removed before any spacecraft were sent on their missions. “But I guess you can say my theoretical fingerprints are there.”