50 years after milestone transplant, his kidney keeps going

Children’s Hospital Los Angeles unites its first pediatric kidney transplant patient with his childhood doctor and the latest donor recipient

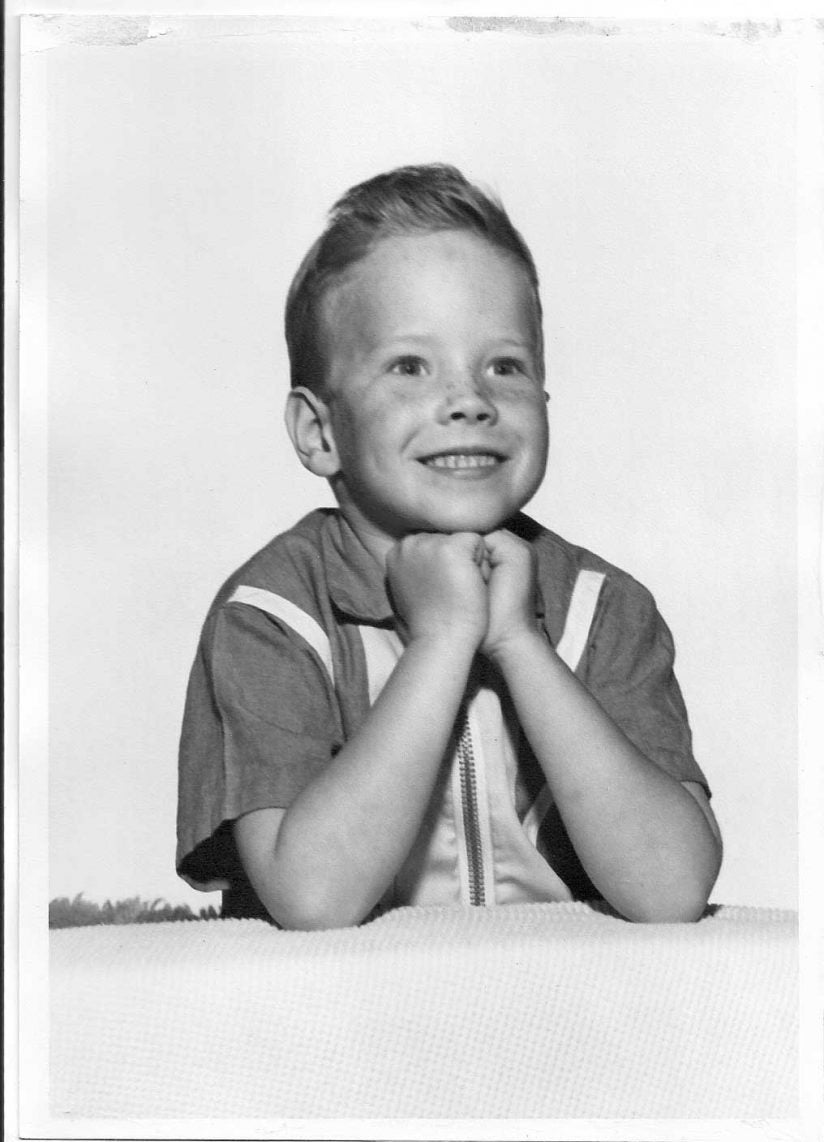

In February 1967, 6-year-old Tommy Hoag became the first Children’s Hospital Los Angeles patient to undergo a kidney transplant. A bout with scarlet fever had left the boy’s kidneys with glomerulonephritis, a disease that damages their ability to filter waste and fluids from the blood.

A team of doctors treating Hoag, including then-CHLA pediatric kidney specialist Richard Fine, had concluded that the only way to save the child’s life was a renal transplant. The procedure was only a few years old at the time, most often done between twins and rarely suggested for children. But blood and tissue tests had shown that Tommy’s father William was a great match and doctors were optimistic.

“I remember being wheeled into the operating room and [my father] was already there and he was happy to see me,” said Hoag, who is now 56 and living in Las Vegas (the family lived in the Reseda at the time of the transplant). “My dad was a baseball fan, a die-hard Dodgers fan and also a Babe Ruth fan. When he saw me, he said, ‘Come on in, Bambino! Let’s get this done!’ ”

And just as Ruth made his mark on the history books, Thomas Hoag’s successful transplant has the distinction of holding one of CHLA’s most notable records — his father’s gift of life has now lasted Thomas 50 years and counting. Hoag’s kidney is, if not the longest, one of the longest functioning live donor kidneys given to a child in U.S. history. It’s rare for a donor kidney to last so long, say doctors, who consider Hoag one of CHLA’s biggest success stories.

“The success of Tommy’s transplant really jump-started the nephrology program here at Children’s Hospital,” said Carl Grushkin, CHLA’s current chief of nephrology and professor of clinical pediatrics at the Keck School of Medicine of USC, who was a resident in 1967 when Hoag’s surgery took place.

To date, the CHLA program has performed nearly 1,100 kidney transplants since 1967 and has one of the most successful transplant programs in the country based on recipient and graft survival.

A special anniversary

On March 7, Hoag and Fine reunited at the hospital for a ceremony held by CHLA’s current nephrology team to mark the 50th anniversary of Hoag’s transplant. Not only was Fine the one who diagnosed Hoag with kidney failure and glomerulonephritis, he was the driving force in starting the dialysis program at CHLA that same year. That program continues to be one of the two largest pediatric dialysis programs in the United States.

“Seeing Tommy here today, seeing how well he’s done for such a long period of time, I think, is one of the highlights of my career,” said Fine, a professor of clinical pediatrics at the Keck School of Medicine. Fine said medical literature in the 1960s discouraged pediatric dialysis and renal transplantation, but he believed it was the only option to save the boy’s life.

“We had no idea 50 years ago that we could accomplish having someone survive with one kidney for 50 years,” he said.

After the ceremony, Hoag also got a chance to sit down and chat with Gemma Lafontant, 14, CHLA’s most recent kidney transplant patient. Lafontant has chronic kidney disease and received a pre-emptive donor kidney on Feb. 21. Pre-emptive transplants are ones that take place before significant kidney failure occurs and are now often recommended to keep a child from needing to start dialysis.

“It’s amazing that his kidneys lasted 50 years,” the teen said. “That could be me.”

Hoag, who spent six months recuperating in the hospital after his procedure, found it remarkable that Lafontant was able to go home less than two weeks after her transplant and was glad to be able to give her some words of encouragement.

“It comes up every now and then that I get asked about being a ‘pioneer,’ ” Hoag said. “It’s not something I tried to get the record on, it’s just something that was obviously meant to be. And it’s worked out well for me and so many others.”