USC poet’s work conveys a passion for the macabre

Anna Journey takes a walk on the dark side in poems and essays about graveyards, infidelities and tattoos

Anna Journey says she’s always had an interest in dark fairy tales and a fascination with the stories her mother told her about her own childhood living on the grounds of a Texas mental asylum while her father, a psychiatrist, did his residency.

“Those were the kinds of stories I grew up hearing,” said Journey, assistant professor of English at the USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences. “They seemed normal to me as a child, and I didn’t realize there was anything unusually macabre about them until much later.”

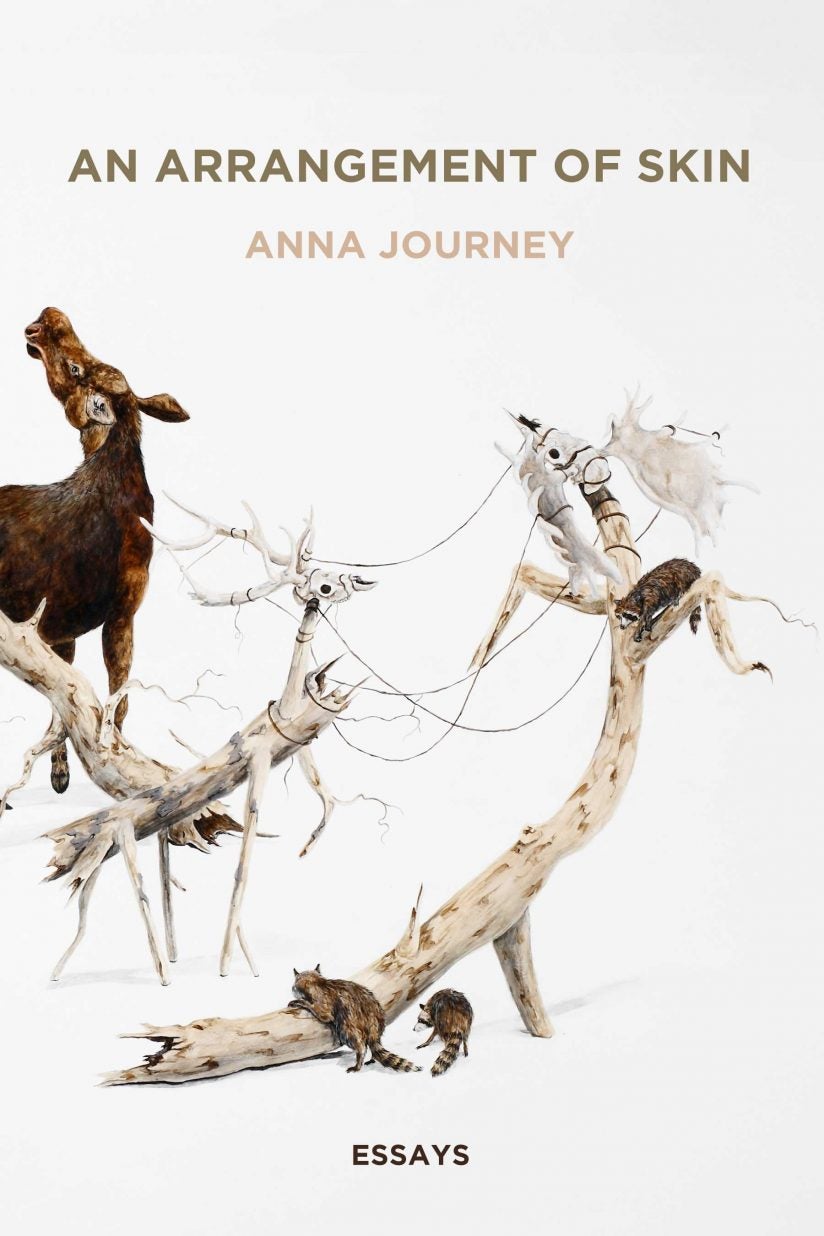

Journey’s first book of essays, An Arrangement of Skin (Counterpoint), features a piece that examines various versions of the “Bluebeard” story, her mother’s favorite fairy tale about the wealthy man who murdered his wives. In it, Journey pays tribute to her mother’s gift for the grotesque, writing, “There isn’t an anecdote out there too terrifying or gruesome or scandalous …. There isn’t a forbidden door in the castle that she won’t unlock.”

Poetry in motion

Journey is also a poet whose third collection of poems, The Atheist Wore Goat Silk (Louisiana State University Press, 2017), was out in February. Her new poems and essays brim with tales of graveyards, taxidermy, infidelity and tattoos.

The Atheist Wore Goat Silk opens with a poem about a barcode tattoo Journey’s speaker gets as a teenage dare. Ten years later, curiosity finally gets the better of her.

Asking a supermarket worker to scan her adolescent protest against consumerism, she discovers the vertical lines inked onto her forearm correspond to sweet potatoes.

“I’ve always been sweet but slightly / twisted,” Journey writes. “I’ve always been waiting to disappear like this, / bite by bite, into someone’s mouth.”

Journey, who skipped her high school prom “out of teenage defiance,” displays more dark humor in two poems devoted to a novelty item she saw advertised by a Kentucky florist: a fried chicken prom corsage.

Written in the genre of a danse macabre, Journey describes how “The golden-breaded / cluster of drumsticks cinched // in their fuschia ribbons and a wrist- // elastic,” finally arouses regret for the missed opportunity to wear one. “You want to see the photographs/ snapped after midnight when the blond prom dates gnaw/ their pink-ribboned corsages to the gristle.”

There is also a poem about blue honey, made by French bees who feasted on “the sugared waste // that dripped from an M&M’s factory.”

“I’ll often take an odd or peculiar story involving science or animals and braid it with another thread that seems more intimate or personal,” Journey said.

Thus, in another tattoo tale, the moving “Trompe-l’oeil for Shannon,” Journey tells the story of the “punk chick” hairdresser near the railroad tracks with the “ribbed, grey, // oval of a roly-poly” tattooed on her elbow.

A childhood spent distracting herself and her younger sister from her parents’ disastrous marriage by observing the tiny insects leads the adult Shannon to get a tattoo of the pill bug on her elbow, where she can make it contract and disappear into its protective armadillo shell at will simply by straightening her arm. The ink becomes a symbol of the hairdresser’s reclaimed power.

Fiction with friction

Describing her poems as closer to fiction than autobiography, Journey warns that we shouldn’t take the extraordinary characters and events they describe too literally.

Even in poems that seem autobiographical, there are lots of invented details — and they may be the more believable ones.

Anna Journey

“Even in poems that seem autobiographical, there are lots of invented details — and they may be the more believable ones,” she said.

The suite of 14 personal essays in An Arrangement of Skin are written with an associative, braided structure more reminiscent of poetry than traditional narrative.

The title, the definition of taxidermy — taxis, an arrangement and derma, skin — is a reference to one of the unifying images that echo through the book.

“The process of arranging seemed to speak to the art of the storyteller,” Journey said, “while the image of skin suggested a metaphor: for bodies, lovers, family members, the different selves we inhabit in our lives.”

In one essay about a taxidermy lesson held in downtown Los Angeles, she compares peeling back the skin of her chosen subject, a starling, to “pushing apart the fuzzy velveteen of a ripe peach.”

As with her poems, there are reoccurring story lines: delicate threads that weave through the intimate narratives that include family stories and the story of an affair and a falling out with a close mentor.

If the poems and essays share similar sensibilities, they also share many reoccurring characters: Journey’s likely closeted grandfather and his longtime lover; a grandmother whose rare disease has given her “swan fingers.”

“This sense of risk and wonder is what I try to carry into both my poems and essays,” Journey said. “It’s also what I hope to share in teaching my students — that writing is a continuous process of discovery.”