USC alumna — part surgeon, part engineer — recalls the dreams that inspired her

Rosa Navarro runs a private practice treating chronic pain, implanting medical devices of her own design

At the U.S.-Mexico border, an immigration officer rubber stamps a passport and unlocks a padlock on a metal door with the sign ¡Bienvenido a Tijuana!

With that bit of perfunctory protocol, the metal door opens, and Rosa Navarro ’85 steps back into the country she left as a girl.

“Crossing the border changes your mindset,” she said. “It’s like stepping back in time.” Ahead is the arch on the Avenida Revolución, like a portal to another world.

When Navarro was 8, she lived in both worlds at once.

“I spent my childhood speaking English in the day and Spanish at night.”

These days, when she returns to her native home, it’s as Dr. Navarro, an internationally renowned expert in neuromodulation who merged engineering and medicine to invent a novel way to treat chronic pain.

Dreams have no borders, only horizons

Back in 1967, “the lady in the station wagon” would pick Navarro up at dawn and drive her across the border, dropping her off at a small Catholic school near San Diego.

At night, back in Tijuana, she watched her mother, Lucia Navarro, a dressmaker, bring grace to every gesture as she put the finishing touches on the wedding gowns and quinceañera dresses that were financing American educations for Navarro and her younger brother. They lived across the street from an orphanage, everyday witnesses to the realities of hardship.

“I don’t recall ever going to a movie theater because it cost money,” Navarro said. “We just didn’t splurge. I grew up thinking I never want to be poor and hungry again.”

Rosa’s father, Daniel Navarro, was a jeweler and watchmaker who had inherited a patch of land from his father, who purchased it long before Tijuana became the Vegas of Mexico or native son Carlos Santana put it in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

Graceful gestures and objects of fascination were everywhere in the modest Navarro household: her mother’s needle threading the silk with pearls, beads and sequins; her father adjusting the miniature gears and springs of ticking watches.

These were all young Rosa’s fixations growing up, and they led to a love of engineering, mathematics and above all, medicine.

“I dreamt of being a doctor since I was a little girl,” Navarro said.

No answers to many questions

But despite their never-ending work, the family was struggling and the path wasn’t clear to her. What did she need to do to become a doctor? How much would school cost? Her parents didn’t know the answers.

“My mother and father had an elementary school education,” Navarro said. “Once I reached high school, they could not help me. They were proud of me, but I was basically on my own. ‘Whatever you want to be, Rosa,’ they’d say.”

In a class full of smart kids, she was one of the smartest, especially with numbers. She also became a veritable competitor in tennis, a sport that pushed her concentration, confidence and limiting beliefs — a perfect metaphor for bouncing across borders while quieting the mind and avoiding self-sabotage — the “inner game.”

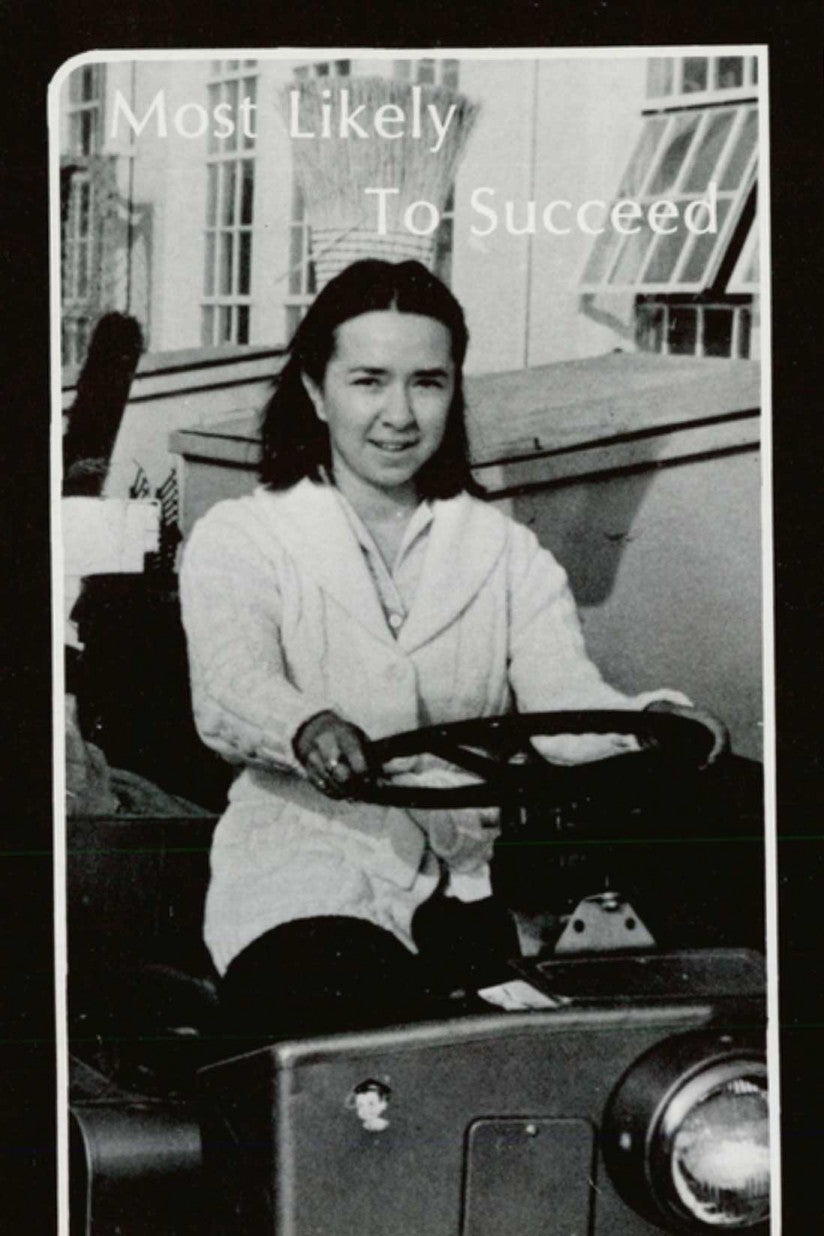

The 1978 graduating class of Santa Ana High voted her Most Likely to Succeed. The girl who crossed the dusty border in a beat up station wagon was facing a wide-open horizon before her.

While attending a math summer camp for minority students, Navarro was noticed by Paul David Arthur, a mechanical engineering professor at the University of California, Irvine, who was so impressed with her mathematical abilities that he drove across the border to plead with her parents to let her go to an American college.

“She has a future in engineering,” Arthur told them.

Her parents looked at her. Their hopes, their sacrifices, their dreams for their daughter came to this moment.

“Is this what you want to be, mija? ” they asked.

“I knew what a doctor was, but what was an engineer? What did an engineer’s day look like? I’m totally clueless,” Navarro remembered thinking.

Grateful that Arthur saw her potential, yet blind to the profession, she made a life decision that summer. She was going to be an engineer. And she was going to start at USC.

New beginnings

It was the financial support that drew her to join the Trojans. She received a scholarship from the USC Mexican-American Alumni Association, a university scholarship coupled with several engineering scholarships.

“Lots of scholarships,” Navarro said. “That’s how I made it to USC.” One summer she sold cars for Ford. Then she did a stint as a courier delivering packages across Los Angeles. She was also a nanny.

All of this was balanced with the overwhelming course-load of a double major: electrical and biomedical engineering.

Somehow Navarro also found the time to fall in love and marry a fellow student. She gave birth to a son, Arthur, named after the professor who inspired her to become an engineer. Unfortunately, the marriage was short-lived and soon she was a full-time student and single mother working to support her education and son.

The dream of being a doctor was suddenly and painfully out of reach.

My son was with me throughout all those challenges. And my inspiration to keep going.

Rosa Navarro

“My son was with me throughout all those challenges,” Navarro said. “And my inspiration to keep going.”

She joined Eugene Albright’s lab in what is now the Keck School of Medicine of USC as his research assistant and stayed close to the heart of medicine for the last two years of college.

When Navarro graduated in 1985, she remembers being “the only Hispanic woman in the engineering graduating class.” It was then that she realized what a trailblazer she truly was.

Sadly, her parents were unable to share in the momentous occasion. They celebrated her from afar. The family she had become close with, the ones she babysat for, attended as surrogates alongside little Arthur.

NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory promptly recruited her. She stayed on for six years as part of the scale integration design team. Navarro described her work as “basically, reverse-engineering microprocessors to detect faults in parts that NASA sent to space.”

Rekindled dreams

By 24, Navarro had become a sought-after speaker, representing JPL at international conferences in Italy and Mexico.

Those visits to Mexico rekindled the doctor dream like never before. Being an international speaker for NASA felt like a career high, but it just wasn’t enough. Not when the dream of that little girl crossing the border remained unfulfilled.

“Is this what you want to be, mija?” still lingered. Especially now that Arthur was growing up.

She decided she was going to take the MCAT. Arthur was 6 years old and about to start elementary school.

“If I’m ever going to do this, now is the time,” Navarro remembered telling herself. “Time to chase the dream again. For me and for Arthur.”

To her shock, no less then six medical schools accepted her. She chose the University of Illinois. Her engineering background immediately made her a standout student. She even created a job for herself.

“I paid my way through medical school by opening a computer lab for medical students. We didn’t have a way to produce notes en masse.”

She repaired donated computers, created a LAN network and devised a systems approach to sharing anatomy class notes.

“My engineering skills paid off.”

Navarro finished her residency in anesthesiology at the University of Chicago. She went on to complete a pain management fellowship at Georgetown University Hospital in Washington, D.C. Back home in Tijuana, her family stood a little taller among neighbors and friends. Navarro had become a doctor and not just anywhere, but in America’s capital.

The good doctor

Rosa Navarro now has her own private practice treating acute and chronic pain in Chula Vista — the Navarro Pain Control Group Inc. — primarily servicing the Hispanic community. Part surgeon, part engineer, Navarro implants medical devices designed by her to treat conditions such as back and neck pain, degenerative disc disease, spinal stenosis and cancer pain among others.

She also holds several medical technology patents, is the treasurer of the North American Society of Women in Neuromodulation and board certified in anesthesiology and pain medicine.

Navarro’s patents include a novel system for treating pain using spinal cord stimulation and peripheral subcutaneous stimulation separately or in combination.

She surgically implants a device configured to deliver electrical signals between a patient’s subcutaneous lumbar region and the spinal cord. Not only does it treat patients who either can’t take or are otherwise unresponsive to certain pain meds, her innovative therapy accelerates the body’s natural ability to heal itself.

At the California Institute of Technology, she also met her future husband, a biomedical engineer who worked on JPL’s hypercube and who is now an anesthesiologist himself. The couple’s son, Gregory, is now in the process of applying to USC to study engineering. In fact, both of Rosa’s sons followed in her footsteps.

Arthur is a mechanical engineer who was instrumental in the building of the Children’s National Medical Center in Washington D.C.

“Before my father passed away, he was a role model to my oldest boy and his love of construction passed on to Arthur,” Navarro said.

As for her mother, she is now 85, living with her daughter and son-in-law in their San Diego home.

Navarro never forgot where she came from and continues to give talks and attend conferences throughout Mexico, inspiring young people to never stop pursuing their dreams.

“Always have your goal in front of you and stay focused. So many things can happen to you in life. Bring it back into focus and stay on target. Make that commitment.”