Inequality remains about the same in Hollywood films, USC study finds

The report reveals that representation of gender, race/ethnicity, LGBT status and even disability lags on screen and behind the camera

A new USC report reveals that little has changed on screen or behind the camera regarding inequality in Hollywood.

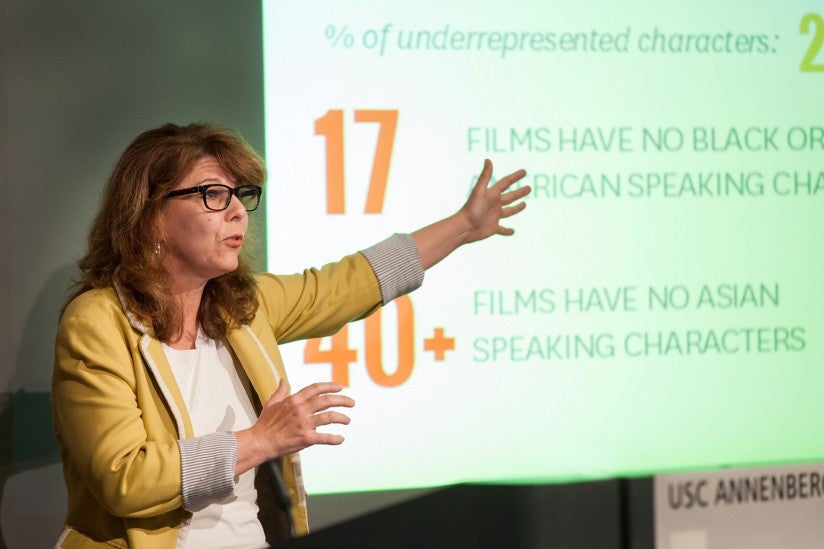

The study examined 800 films from 2007 to 2015 (excluding 2011), analyzing 35,205 characters for gender, race/ethnicity, LGBT status and for the first time, the presence of disability. It was authored by Professor Stacy Smith and the Media, Diversity & Social Change Initiative at the USC Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism.

According to the study, 31.4 percent of all speaking characters across the 100 top films from 2015 were female, a figure that has not changed since 2007. While race/ethnicity has been a major focus of advocacy in the wake of #OscarsSoWhite, only 26.3 percent of all characters were from underrepresented racial/ethnic groups. LGBT-identified characters represented less than 1 percent of all speaking characters. The report includes data on characters with disabilities, who filled just 2.4 percent of all speaking roles.

“The findings reveal that Hollywood is an epicenter of cultural inequality,” said Smith, founding director of the MDSC Initiative. “While the voices calling for change have escalated in number and volume, there is little evidence that this has transformed the movies that we see and the people hired to create them. Our reports demonstrate that the problems are pervasive and systemic.”

Of the top 100 films of 2015, 49 included no Asian or Asian-American characters and 17 featured no black/African-American characters. Similarly, 45 films did not include a character with a disability and 82 did not feature a lesbian, gay, bisexual or transgender character.

One bright spot was an 11 percent increase in female lead or co-lead characters from 2014 to 2015. But only three of the films featured a female lead or co-lead actor from an underrepresented racial/ethnic group. None of the males or females in leading roles was Asian, echoing the concerns expressed by prominent Asian and Asian-American actors and others in that community.

Off-camera findings

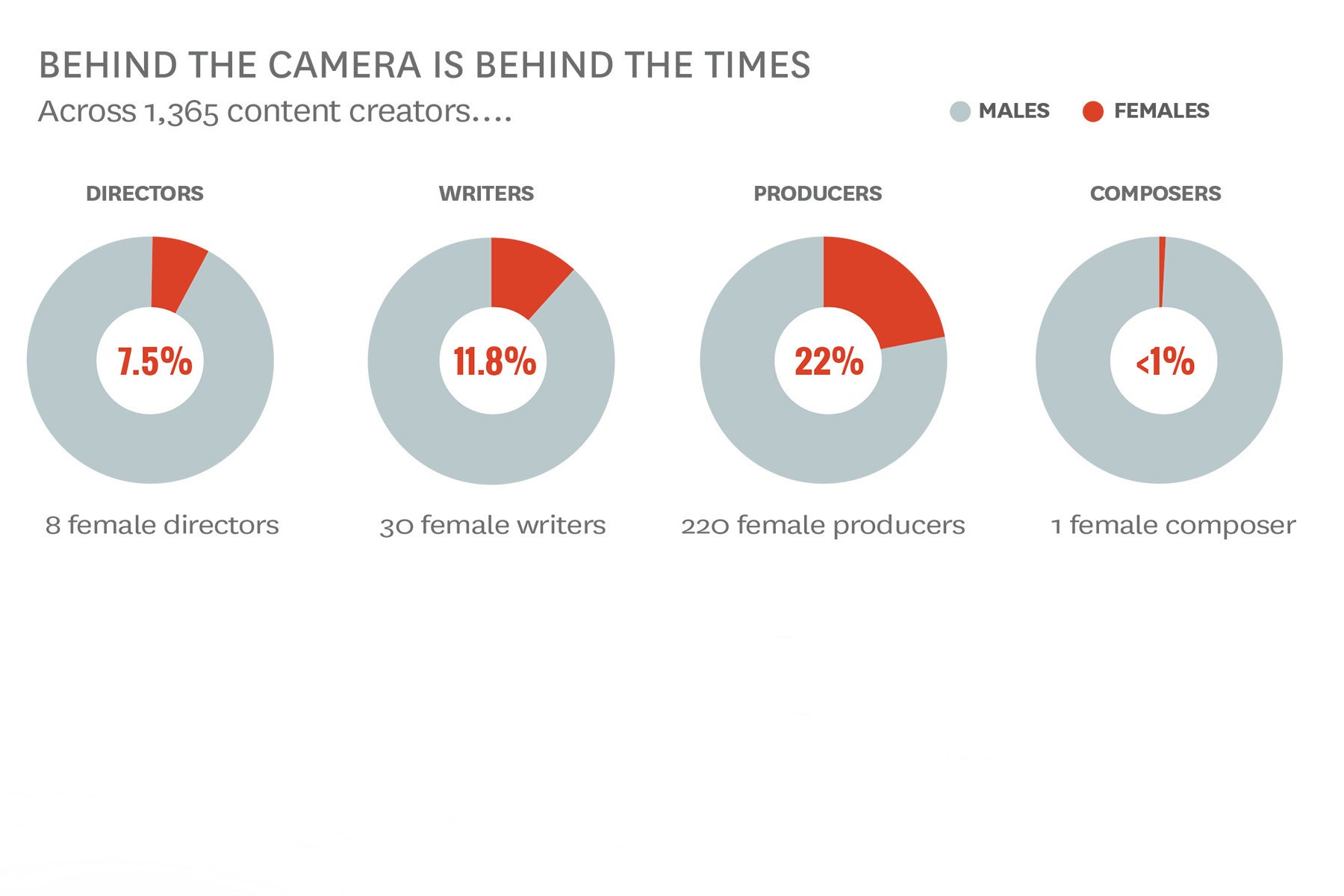

Behind the camera, female directors represented just 4.1 percent of those hired on the 800 films evaluated. Women of color were nearly absent from those ranks, with just three black or African-American females and one Asian female in the director’s chair. Overall, directors from underrepresented racial groups fared poorly. Only 5.5 percent of the 886 directors examined were black or African-American and 2.8 percent were Asian or Asian American.

“Despite the advocacy surrounding female directors, film is a representational wasteland for women of color in this key role,” Smith said. “Advocates need to ensure that their work reflects the barriers facing all women, not just a select few.”

For the first time, the researchers collected data on characters with disabilities. Most of the characters were played by males and no LGBT characters were depicted, according to the study sample.

“This is a new low for gender inequality,” Smith said. “The small number of portrayals of disability is concerning, as is the fact that they do not depict the diversity within this community.”

The report provides multiple solutions to addressing what Smith has previously referred to as the “inclusion crisis” facing Hollywood. These include strategies for reaching gender equality on screen within three years.

“Raised voices and calls for change are important, but so are practical and strategic solutions based on research,” said Katherine Pieper, one of the study’s co-authors. “The momentum created by activism needs to be matched with realistic tactics for creating change.”