Gary Michelson: Man with a Plan

At USC, philanthropist Gary Michelson just put scientists’ and engineers’ efforts into overdrive.

Gary Michelson fixes people, machines and all things broken. His natural leaning toward finding solutions to problems may come from a will deep inside him to ease suffering. It may also partly come from his desire to build a world that simply works better.

One of the most important things to inventing is the permission to fail.

Gary Michelson

Michelson grew up seeing his once-athletic grandmother struggle with debilitating back issues, even at a young age. “If it hadn’t been for her very strong will to walk, my grandmother would have been in a wheelchair,” says Michelson, now a successful spinal surgeon and serial inventor.

He was also a born tinkerer who once found a broken record player in a Dumpster, took it apart and brought it back to life. Coming of age in Philadelphia, “I was the only kid on my block with a record player,” he says.

The early lessons of putting pieces together have stuck with him.

“One of the most important things to inventing is the permission to fail,” he says. Despite struggling in high school (Michelson says he “didn’t so much graduate as the teachers couldn’t stand the idea of looking at me for another year and kicked me on through”), he went to medical school and chose to become an orthopaedic surgeon.

He Looks for Answers

After medical school, Michelson dedicated himself to inventing new surgical procedures, tools and implants to allow surgeons to achieve vastly improved results. Facing the universal frustration of a back surgeon—that patients often still had pain after their operations—he worked to create tools that would enable surgeons to operate more gently and precisely. He brought out his old physics textbook and studied mechanics, but in earnest this time. He penciled out drawings and shaped his medical inventions in metal and plastic.

Now, the products and procedures Michelson created have reached countless spinal patients. If orthopedic surgeons ever installed a plate on the front of the delicate bones in your neck to protect and stabilize your spine during a fusion, his inventions have played a part in your operation. And surgeons all over the world use devices based on Michelson’s technology as artificial spacers between bones of the spine during fusion procedures, alleviating the back and neck pain that plagues so many.

In all, he holds more than 950 issued or pending patents worldwide for instruments, procedures and medical devices related to the treatment of spinal disorders.

A Grand Vision

A Grand Vision

Michelson didn’t attend USC, but “I’m thinking about taking a money-management course there,” he says with a laugh. In seriousness, he came to know the university and partner with it because they share a similar motivation. Its vision for science with practical results, he explains, matches his own.

“Universities have been notorious for the purity of scientific research, and from the inside looking out, they take pride in doing science for science’s sake,” he says. “USC and I share a sense of impatience that prefers a more purposefully directed approach.”

In other words, both want to see science and engineering come together to improve lives. This shared vision will take shape in the USC Michelson Center for Convergent Bioscience, set to break ground later this year thanks to his $50 million gift. Engineers will mingle with molecular scientists at the center to tackle the challenges of the modern biomedicine era.

“Dr. Michelson’s generous gift is truly visionary, as it will bridge USC’s strengths in a broad range of disciplines, including the sciences, engineering, medicine, mathematics and computer science,” says USC President C. L. Max Nikias.

Cancer and chronic diseases could be a place to start: Diabetes alone affects 370 million people today and will touch as many as 440 million people by 2020. Within the center, faculty and students also will try to boost food production through molecular techniques, generate alternative energy sources, and address environmental and climate change.

An Accelerant for Ideas

Michelson has seen the power of bringing people together to push other great leaps, such as the decoding of the human genome, an international project that spanned decades.

Biologists and computer scientists had to work together with theoretical mathematicians to crack the data. “So I think the issue is, how do you get all these brilliant masters of their own subspecialized fields of science to work together in a convergent way to solve real-world problems?” he says.

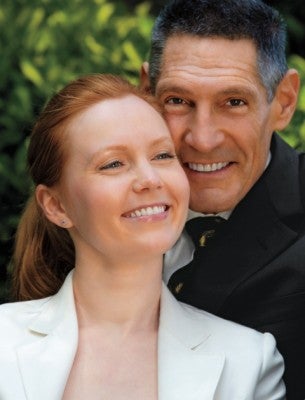

Three examples of his dedication to the pursuit of convergent research live—and bark—in his own home. He and his wife, Alya, have adopted three rescue dogs: a whippet named Gracie, a German shepherd named Abby and a pit bull named Honey. An animal lover who understands the effects of animal overpopulation, Michelson started a foundation that offers a $25 million prize for scientists who come up with a sterilizing injection that could easily be given to a cat or dog, male or female.

Michelson embodies invention and the merging of science and engineering to solve human health challenges. Over time, he’s made it his life’s work to spur others along in the pursuit of elegant solutions to these problems. The words of Edwin Land, who created the Polaroid instant camera, might best sum up his belief in the power of the creative scientific process, Michelson says: “It’s an interesting quality of science. Once you solve the problem, the solution seems almost obvious.”