The Great Zamperini

Louis Zamperini fought off sharks and met Adolf Hitler at the Berlin Olympics. Now what?

Louis Zamperini is 86 years old. His doctors at the VA say they’ve never met a man quite like him. “I’ve got 110/60, a 60 pulse, 185 cholesterol,” he says, grinning as he rattles off the enviable stats. “I’m told I have the vitals of a 35-year-old. And with all I’ve been through, they thought I’d be dead by 55! I almost did lose a kidney after being dehydrated on that raft and fighting those sharks. But the kidney bounced back.”

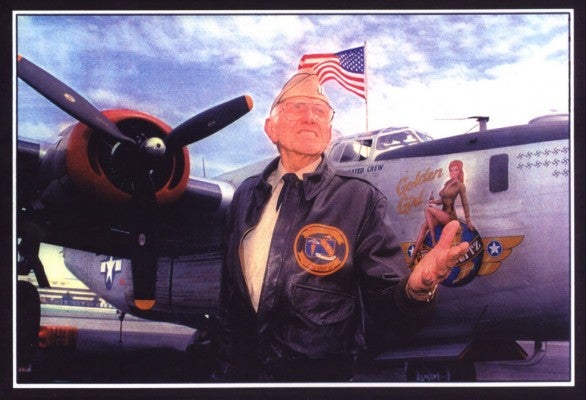

Zamperini is, of course, referring to the time when, as a World War II bombardier, he crashed over the Pacific and drifted for 47 days on a life raft, only to be taken captive by the Japanese for more than two years. And then there’s the episode during the 1936 Olympics when he was singled out for a handshake by Adolf Hitler, and the time he lifted a swastika-emblazoned banner off a Reichstag flagpole. His death-defying life of derring-do sounds like something out of a book – so, obligingly, he’s compiled these and other remarkable chapters into Devil at My Heels: A World War II Hero’s Epic Saga of Torment, Survival, and Forgiveness (William Morrow / HarperCollins 2003). Released in February 2003, the memoir “contains the wisdom of a life well lived, by a man who sacrificed more for it than many people would dare to imagine,” writes Sen. John McCain in the foreword. Nicolas Cage may soon be playing “Lucky Louie” in the Universal Pictures film version. And don’t be surprised if Zamperini has still more adventures up his sleeve – despite his advanced years, he’s got energy in spades (not to mention those great vital signs). When he isn’t writing and traveling to speaking engagements, he still skis regularly and flies stunts in his World War II-era plane.

Humble beginnings

Lou Zamperini’s life could have taken a whole other path, given its hard-scrabble start. “My parents really loved me, but I kept getting into trouble,” he says contritely. The son of Italian immigrants, he spoke no English when his family moved to Torrance, Calif., a trait that quickly attracted the attention of neighborhood bullies. His father taught him how to box in self-defense, and pretty soon “I was beating the tar out of every one of them,” he says, chuckling. “But I was so good at it that I started relishing the idea of getting even. I was sort of addicted to it.”

Before long he was picking fights just to see if anyone could keep up with him. From juvenile thug, he progressed to “teenage hobo.” Hopping a train to Mexico, he courted danger for the thrill of it. “I caught a wild cow in a ravine and tore my kneecap till it was just hanging off,” he recalls. “I snapped my big toe jumping out of some giant bamboo; they just sewed it back on. I’ve got so many scars, they’re criss-crossing each other!”

With the help of his older brother Pete, Zamperini eventually channeled his bad-boy energies into running. At Torrance High School he proved a gifted miler (in spite of that torn kneecap and severed big toe); as a junior in 1934, he was invited to run against Pacific Coast college champions in the Los Angeles Coliseum. Zamperini blew the competition away, setting a new interscholastic mile world record of 4:21.20 (it stood for 20 years) and winning by 25 yards.

“I was presented with a gold watch by the actor Adolphe Menjou,” he crows.

When “the Tornado from Torrance” graduated, he was invited to train for the 1936 Olympic team at the USC track; he subsequently entered USC on a scholarship. Under coach Dean Cromwell, Zamperini set a national collegiate mile mark of 4:08.3 that stood for 15 years, and in 1940 he ran an indoor mile in 4:07.6 at Madison Square Garden.

Too bad his luck didn’t hold in Berlin, where Zamperini threw away his once-in-a-lifetime chance at Olympic glory.

“Well, you have to understand what those times were like,” he says sheepishly. “I was a Depression-era kid who had never even been to a drugstore for a sandwich. Here I was, leaving Torrance, going on a train to New York City, going on a boat to Germany. This was more exciting to me than making the [Olympic] team. And all the food was free. I had not just one sweet roll, but about seven every morning, with bacon and eggs. My eyes were like saucers.”

By the end of the trans-Atlantic voyage, the saucer-eyed Olympic hopeful had put on 12 pounds. With this extra cargo packed onto his kinetic frame, Zamperini finished the 5,000 meter in eighth place, with a time of 14:45.8. Even so, he managed to delight an arena full of spectators, including Adolf Hitler.

“It was quite a sight,” he recalls. “Though I’d been behind, I sprinted the whole last lap, running it in 56 seconds after three whole miles. The crowd was going nuts.”

Afterward, as photographers snapped Zamperini’s picture, Hitler’s chief propagandist invited the young American runner to come shake hands with the Nazi leader. “Aha! The boy with the fast finish!” Hitler said to Zamperini through an English interpreter.

Ironically, in his next life-and-death crisis, it was academics, not athletics, that would save Zamperini: specifically, the teachings of USC physical education professor Eugene Roberts.

Ask Zamperini what he thought of the dictator, and he pauses to reflect: “It wasn’t until many years later that I looked back and realized I’d shaken hands with the worst tyrant the world has ever known.” His impression at the time was of a man with “an annoying disposition, like a dangerous comedian.”

The young Olympian’s off-the-track exploits were equally sensational. One of his bunkmates was famed sprinter Jesse Owens. “He was a prince of a guy, a sweet, humble man,” Zamperini recalls. “The coach told him to keep an eye out for me because I was, you know, a bit frisky – and they were letting us go out into the city at night.”

Apparently Owens wasn’t watchful enough, because Zamperini almost lost his life again, executing a harebrained prank: trying to snatch a Third Reich souvenir.

“They don’t have small-sized beers in Germany,” Zamperini says, by way of excuse for his lunatic caper. “I was drinking in a pub across from the Reichstag where some Nazi flags were flying, and I thought, ‘I’ve got to have that flag for a souvenir.’”

The inebriated American had already clambered up the flagpole when he heard the guards shouting and firing in the air. Zamperini’s German consisted of a single word: bier. All the same he got the point; meekly climbing down, he offered flattery: “I wanted to take it home to remember my wonderful time here,” he told the guards in English. After conferring with their colonel, the soldiers decided to let the crazy athlete have his souvenir. (That flag, along with the ring from Adolphe Menjou and many other souvenirs, are now part of the Zamperini Museum, kept in the attic of his Hollywood home.)

Ironically, in his next life-and-death crisis, it was academics, not athletics, that would save Zamperini: specifically, the teachings of USC physical education professor Eugene Roberts. “Dr. Roberts really inspired us,” Zamperini recalls. “He taught us about the human body, what muscles we were using. He also taught us to take inventory of our minds, to think before we opened our mouths. A good lesson in mind over matter.”

After the Olympics and graduation from USC, Zamperini had planned to continue competing as an athlete; he was favored to take a victory lap in the 1940 Games. But World War II intervened, and instead of training on the track, he trained as an Army Air Corps bombardier.

A will to survive

“My life as a teenage delinquent had conditioned me for the war,” Zamperini says. But it was his USC lessons in mind over matter that saved him.

In May 1943, during a search-and-rescue mission 800 miles south of Hawaii, his B-24 went down over the Pacific. (Remarkably, Zamperini’s Trojan ring hooked onto the plane’s shattered window frame, enabling him to hoist himself free of the sinking craft.) He and two other survivors drifted 2,000 miles on a life raft with rations of only a few bottles of water and six chocolate bars. When those ran out, they subsisted on tiny fish, sharks, birds and rainwater.

To break his spirit, Sasaki forced him to run a relay race against well-fed Japanese runners. Despite his near-skeletal condition, he prevailed.

“It really was a test of survival,” says Zamperini. “As we drifted, I remembered Dr. Roberts. He taught us to exercise all sections of the brain. Though the other guys never knew it, every morning I took inventory to see how we all were doing mentally.”

Zamperini quizzed them about their childhoods, coaxed them into crooning hymns and Bing Crosby tunes and cooked “imaginary meals” for breakfast, lunch and dinner – “with brain-teasers about how many eggs, how much baking powder to use. There was never a dull moment on that raft,” he says. They fended off sharks by bludgeoning them with paddles. Fired on by a Japanese bomber, they miraculously escaped the aerial onslaught without injury and spent the next eight days repairing their bullet-riddled, waterlogged rubber raft.

On the 33rd day, the tail gunner died. “We slipped him overboard, a burial at sea,” Zamperini wrote in his autobiography. On the 47th day, they made landfall in the Marshall Islands and were promptly taken prisoner by the Japanese. Zamperini’s toned 165-pound frame had shrunk to a skeletal 70 pounds. His ordeal was far from finished.

Over the next two-and-a-half years, Zamperini was threatened with beheading, subjected to medical experiments, routinely beaten, starved, forced into slave labor and hidden in a secret interrogation facility. He was moved from one dungeon and concentration camp to the next, from Kwajalein Island to Truk Island, and on. “At Yokohama, I helped unload 10,000-ton ships, shoveling out coal and refuse from the latrine. “The guards always had their favorite punishment for you, like doing push-ups over the latrine, then pushing your head in it,” he recalls.

Sick with a high fever and falling behind, Zamperini recalls one camp guard screaming at him: “You lick your boots, or you die!” When Zamperini refused, the guard cracked him on the head with his belt buckle, then ordered him to hold a wooden beam over his head. Zamperini lasted 37 minutes before passing out.

Kept in a state of near starvation, he recalls being forced to eat rice off the floor, tossed there by high-ranking Japanese officials “all dressed in white with gold braid, dining on delicious-looking meals in front of us.”

During one memorable interrogation in Ofuna, a camp outside Yokohama, Zamperini’s USC days came flooding back. Looking up at his interrogator, he recognized an old acquaintance.

“Hello, Louis,” said the familiar, suave voice of James Sasaki. “It’s been a long time since USC.” Sasaki had studied at Harvard, Princeton and Yale before attending USC. Despite a 10-year age difference, the two men had shared a love of sports and a large circle of Japanese-American friends in the South Bay.

Now here he was again, questioning a beaten, starved Zamperini. “I remember thinking, that guy couldn’t have been a Trojan. He must have transferred from UCLA,” Zamperini says jokingly.

Zamperini later learned that Sasaki had been a Japanese spy back in their student days, reporting back to his operatives on ship movements in the harbor at Long Beach. When the war came, Sasaki had fled to Japan and eventually had been placed in charge of 91 POW camps.

Hoping to capitalize on Zamperini’s status as a former U.S. Olympian, Sasaki tried to recruit his old classmate to broadcast anti-American propaganda. Zamperini declined. To break his spirit, Sasaki forced him to run a relay race against well-fed Japanese runners. Despite his near-skeletal condition, he prevailed.

“He kept [reminding] me about the food in the Student Union. You can imagine how I felt about it at that point,” groans Zamperini.

With his liberation from the POW camp in September 1945, Zamperini once again made headlines – a war hero returned from the dead. In a Red Cross mess in Yokohama where hungry soldiers elbowed their way toward coffee, donuts and Coke, a New York Times reporter approached him, trolling for a story.

“What’s your name, soldier?” the reporter asked the emaciated second lieutenant.

“Louis Zamperini.”

“It can’t be. Zamperini’s dead,” the reporter replied.

Reaching for his wallet, Zamperini produced his USC Silver Life Pass, good for admission to all Trojan games. (Only athletes who had lettered three years in a row got the sterling pass engraved with their names.) It was the sole ID Zamperini’s captors had left him. The reporter blinked, gazed and proceeded to bombard the missing bombardier with questions.

“I was so mad,” Zamperini recalls, more interested in food than fame at that moment. “All I could think about was the donuts. I ended up searching on the floor for chunks.”

Zamperini’s rescue made the front pages of both the New York Times and the Los Angeles Times, and he was given a hero’s welcome upon his return stateside.

“I must have lived two lifetimes in that six-month period,” he says. “I was invited to a million parties. At Warner Brothers, John Ford filmed an all-studio party for the boys coming home. I got to dance with Maureen O’Hara. Any bar I went into in Hollywood, I never had to buy a drink.”

Not that money was a problem. His parents had tried returning the national life insurance they had collected upon his “death,” but the government wouldn’t take it back.

Picking up the pieces

As another post-war perk, Zamperini was invited for a two-week rest cure in Miami. “They put us up in a swank hotel, threw us a party, sent us deep-sea fishing. One night, my buddy and I crashed a private party; we saw these two beautiful girls.” One of the dazzling debutantes was Cynthia Applewhite.

“It was love at first sight,” says Zamperini. A whirlwind two-week romance ended in a marriage proposal. They were together for 55 years (until her death in 2001), raising two kids, Cissy and Luke.

He revisited emotional terrain he hadn’t seen since he was a teen. And he was haunted by memories of his captivity.

His days of athletic prowess were over, but Zamperini settled into post-war life energetically. He went into war surplus, selling Quonset huts and other materials to the studios. He also sold commercial real estate and was invited, as a community leader, to join the state legislature (he declined, citing a business conflict of interest).

But psychologically, these years proved more tumultuous than Zamperini had anticipated. He revisited emotional terrain he hadn’t seen since he was a teen. And he was haunted by memories of his captivity.

“I was all churned up inside,” he says. “All I could think about was revenge. I’d dream about strangling my prison guards. One night while half-asleep, I grabbed Cynthia around the neck.” Zamperini figured if he got drunk enough, the dreams would stop. His turning to liquor only made Cynthia return to her mother. “When she started talking about a divorce, I knew something had to change,” Zamperini says.

Instead of divorce, his wife turned the other cheek and found solace in the sermons of a preacher named Billy Graham. She tried to get her husband to convert too. At first, he was resistant. “I hated all that holy roller stuff,” he says disdainfully. When Zamperini finally went to a meeting, he was surprised to find Graham “so handsome and clean-cut, not one of those wheezer types.”

During that sermon, Zamperini had an epiphany. “I momentarily flashed to the life raft in the Pacific, the moment when I prayed to God that if He spared my life, that I’d dedicate it to service and prayer – you know all those promises you make when you’re in a jam,” Zamperini says. “I realized then that I’d turned my back on my promises and on God. And when I got off my knees that day in the tent, I knew I would be through with drinking, smoking and revenge fantasies. I haven’t had a nightmare since.”

Inspired by Graham and the Bible, Zamperini toured as a public speaker, channeling his energies into messages of forgiveness. He revisited Japan in 1950, and before large forums of Japanese civilians (as well as the Tokyo Trojan Club), he spread the gospel.

At first, it was a test “to see how I’d deal face-to-face with the people who’d beaten me so badly,” he says. He got his wish: at a gathering, he saw one of his former POW guards. Zamperini felt forgiveness rush through him. “I threw my arms around him,” he recalls. Terrified, the Japanese man fled. What had started as a personal test became a mission of reconciliation. He systematically sought out his captors, finding many in Sugamo Prison awaiting war-crimes trials. He embraced them, tried to convert them (with some success) and in some cases even pleaded for clemency on their behalf. At Sugamo, Zamperini even found his former classmate and tormentor Sasaki. The American hero appealed to the war-crimes tribunal to soften Sasaki’s 10-year sentence, to no avail. Sasaki was released in a 1952 national amnesty. He was reported to have died in 1979.

CBS aired a segment on Zamperini’s odyssey that a Houston Chronicle sportswriter called “the very best thing I saw on sports television, period, in 1998.”

The remaining years have been busy for Lou Zamperini. He founded the Outward Bound-style Victory Boys Camp program, and has been invited around the world to help initiate similar programs in Germany, Australia and England. The Worldwide Forgiveness Alliance named him a 1999 “Hero of Forgiveness.” A year earlier, he had returned once again to Japan – this time carrying the Olympic torch (as he had in Los Angeles and Atlanta) through Nagano. The route took him right past one of the many concentration camps where he had been imprisoned. CBS aired a segment on Zamperini’s odyssey that a Houston Chronicle sportswriter called “the very best thing I saw on sports television, period, in 1998.” The press universally praised the 35-minute piece, which later won an Emmy.

At his Hollywood home, the souvenirs of an astonishing lifetime are coming together in his beloved Zamperini Museum. (Included in the collection are his stolen Nazi flag, two World War II bombs he brought back and a piece of the Hollywood sign he found while hiking one day near his house.)

He continues to tour as a speaker – in prisons, schools and elsewhere – discussing issues of motivation and reconciliation. Zamperini still insists that his USC lessons from Dr. Roberts were among the most valuable he ever learned.

“I tell kids to be aware of what’s going on around them, in the street, in class, to size up the situation, think of the consequences,” he says. “It’s the one thing schools neglect to teach in the classrooms, and it’s the answer to all the choices we make and to all survival in this world.”

He pauses, then clarifies: “Roberts called it mind-over-matter. But you could also call it wisdom.”

The following excerpt is from Devil at my Heels: A World War II Hero’s Epic Saga of Torment, Survival, and Forgiveness by Louis Zamperini with David Rensin. Copyright © 2003 by Louis Zamperini. Reprinted by permission of William Morrow and Co., an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

Rescue Or Raid?

Praying for rescue, Zamperini and his companions heard the drone of an airplane engine and thought their ordeal was ending. They were miserably mistaken.

On the 27th day I heard a noise overhead. I looked up and saw a plane almost too distant to do us any good. Desperate, we took a quick vote and decided to use two parachute flares plus one packet of dye in the ocean to attract the plane’s attention. I also used the mirror to flicker at them, but the plane disappeared.

Then suddenly it reappeared, descending. They had seen us.

That was probably the most emotional moment of out lives, three grown men, tears running down our faces because we knew we’d be rescued. Man, it was great. The plane – it looked like a B-25 – circled. We waved our shirts and screamed.

In return we got machine-gun fire.

“Those idiots!” I yelled. They thought we were Japanese. Then I saw the red circles, the rising sun, on their wing tips. The plane was a Japanese Sally bomber, which looks similar to our B-25. They were Japanese!

I slid into the water and hung below the rafts to avoid the bullets. Phil and Mac did the same. My Boy Scout leader had told me that water would stop bullets after about three feet. He was right…. I could see the bullets pierce the raft only to slow and sink harmlessly. We weren’t hit.

When it was safe, Phil and Mac tried to get back in the raft. They were so weak I had to boost them both…. [I preferred] to socialize with two seven-foot sharks than be an easy target for the enemy.

The strafing continued for nearly 30 minutes. Each time I told them to lay out, dangle their arms, attract no attention, pretend they were dead. Otherwise they had no chance.

Then the Japanese made a pass without firing, and I assumed Phil and Mac were gone….

But moments later the plane returned, this time directly on course. I … looked up to see the bomb-bay doors open. I thought, Oh, no! Sure enough, a black object emerged: a depth charge. It was the ultimate in barbarism, a little extra target practice. I stopped breathing, waiting for the terrible blow to shatter the sea. It landed 30 to 50 feet away – but didn’t explode….

Then the Japanese disappeared, leaving two wrinkled rafts, riddled with bullets, rapidly deflating, and three desperate men not certain they’d survive another day.