Smart buildings that keep us comfy and content might happen sooner than you think

USC experts in architecture, engineering and other disciplines turn our passive surroundings into responsive structures that promote productivity and well-being

The battle over the thermostat is a universal experience. Co-workers and spouses alike regularly argue about the temperature. It always seems to be too hot or too cold for someone in the room.

But what if our indoor environment took care of itself automatically, calibrating to the ideal setting for everyone in the space? That’s the vision of a team of USC researchers led by Joon-Ho Choi, assistant professor of building science at the USC School of Architecture.

“Instead of adjusting your thermostat, the building will be constantly reacting to human physiological signals like your heart rate, skin temperature and skin moisture to maintain a condition that is the best fit to your comfort,” Choi said.

Automated temperature controls are just one aspect of what the researchers see as the future of our built environment — smart buildings that use biosensors to create the best settings for happiness and productivity.

In addition to developing smart devices that control temperature, they’re exploring lighting designs that instantly fine-tune themselves using indicators like pupil size. They envision extending their work to other areas of building science, like acoustics and humidity levels.

“These kinds of human factors are relatively untouched in the research domain,” Choi said. “But they can greatly affect human health, productivity and well-being.”

Smart buildings promise comfort and control

The specialists in Choi’s Human-Building Integration Lab and other experts at USC see their work as part of a movement to expand building design beyond a focus on energy savings and efficiency. Once a novel approach, sustainability has become an expectation for many new structures. Architects and engineers are now being pressed to emphasize personal comfort and well-being.

“We believe that we have to be well to do well,” said Shrikanth Narayanan, a USC professor of electrical engineering, computer science, linguistics, psychology, neuroscience and pediatrics who is collaborating with Choi. “Individual needs ebb and flow — they change. This whole line of work is about how the built environment can respond to our needs.”

Beyond improving the atmosphere of offices and homes, smart building technology could benefit people in other places like hospitals and schools, Narayanan said. He even envisions using these climate-tailoring tools in other engineered environments like vehicles and public transit.

For now, Choi’s team is focusing on temperature controls in the typical office setting. One approach involves providing heating and cooling units at workstations that create microclimates for each employee. Another design calculates the optimal temperature setting for all workers in a shared space.

To help determine whether employees are comfortable, a smart device similar to a fitness tracker can be strapped to the wrist to measure body temperature, sweat and other indicators. The USC team is also exploring the use of computer webcams with an infrared filter to detect facial skin temperature. After developing statistical models that can accurately measure those biological signals in real time, the researchers plan to test their system at a collaborating business in Downtown Los Angeles.

Surveys have shown that employees who work in offices generally complain about them being too cold in the summer and too warm in the winter, Choi said, making them a prime spot for the research.

“That is a serious issue, because of not only energy waste but also productivity loss,” he said. “User-centered controls have a lot of potential to save energy and also increase productivity and health.”

Their work has benefited from early backing through the James H. Zumberge Research and Innovation Fund. The university-wide grant program awards several hundred thousand dollars each year to faculty researchers and is supported by the Zumberge Faculty Research & Innovation Endowment.

Seed funding of $30,000 from the initiative helped the team buy better sensors and other supplies. The investment paid off, leading to a three-year, $300,000 grant from the National Science Foundation to study smart temperature technology. Choi, Narayanan and Maryann Pentz, professor of preventive medicine and director of the USC Institute for Health Promotion & Disease Prevention Research, are overseeing the research.

USC researchers light the way to smarter buildings

Another area that Choi believes could benefit from automated controls is lighting design. In a separate study funded by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, his team hopes to determine the optimal lighting for tasks like reading or working on a computer.

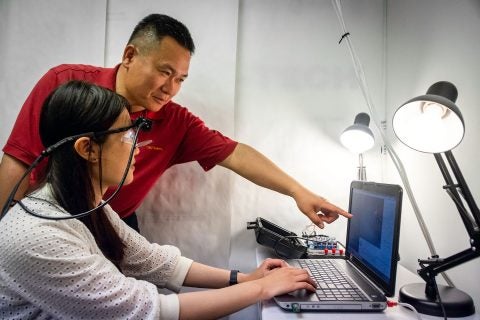

In a basement lab in Watt Hall, the researchers expose study participants to different levels of light in a simulated office environment. A device called a pupillometer measures the size of their pupils, and participants report their level of comfort working in each setting.

“People evaluate the environment very differently,” said Xiaoxin Lin, who has worked with Choi since 2017 and recently completed her master’s degree in building science at the USC School of Architecture. “Some people feel they are most comfortable when the ambient light is very dark, and some feel the opposite.”

She sees potential applications for individualized lighting controls in schools to ensure students can focus on their tasks; in hospitals to provide sufficient illumination for medical personnel while maximizing patient comfort; and even in museums to protect valuable artwork or along roadways to promote traffic safety.

When presenting the team’s initial findings at a conference in Washington, D.C., Lin said many people she talked with about her work reported problems related to poor lighting.

“They complained about similar issues, not only in the workplace but also when they go home,” she said. “Some people said their children want a really dark environment, and they like it brighter and feel very uncomfortable. For everyone, this technology is very meaningful.”

One challenge is ensuring that indicators like pupil size can be measured correctly without being intrusive or requiring bulky equipment. The researchers envision using built-in cameras on computers to measure pupil size and adjust lighting levels accordingly.

Capitalizing on the internet of things and wearable tech

People are increasingly comfortable with wearable technology, using devices ranging from smart watches to activity trackers. The explosion of the internet of things means that more everyday objects are interconnected and exchange data with one another. Wireless sensors are also becoming commonplace, creating a natural environment to start deploying smart building technology.

Early on, the more obvious things like temperature comfort and lighting and other sensory experiences like sound are a good place to start.

Shrikanth Narayanan

“Early on, the more obvious things like temperature comfort and lighting and other sensory experiences like sound are a good place to start,” Narayanan said. “But we don’t know where this will take us.”

He imagines our surroundings adjusting automatically in response to our emotional state. Surfaces could change color to soothe anger or frustration or keep us alert during a late night at the office. Walls could reconfigure themselves to provide a more relaxing environment as we start to wind down for the day.

Narayanan is already making headway in that area in a separate study in the health care world. With the help of Keck Medicine of USC, he is researching how the hospital environment affects nurses emotionally and ultimately influences their workplace behavior and outcomes. Making seemingly minor changes in medical settings could improve performance, reduce stress and promote better care, he said.

As it happens, Choi’s experiences working for a hospital’s facility department while studying for his master’s degree at Texas A&M University inspired him to delve into smart building technology. While repairing lighting systems in hospital rooms, he had the opportunity to talk with patients and their families.

“I found that many of them were lying there in the intensive care unit, unable to do anything but stare up at a fluorescent light all day long,” he said. “The lighting and temperature conditions were 100 percent based on the preference of the nurses and doctors, not the patient.”

User-centered controls for all

That prompted Choi to begin thinking about how to develop user-centered environmental controls and smarter buildings that can respond to all occupants. He sees many opportunities for architects and building scientists in health-related research.

Building design could promote positive mental well-being and recovery from trauma. Designers also could develop integrated systems in buildings to constantly monitor patients’ vital signs, even if they’re not connected to monitors at their hospital bed.

Choi expects major progress in the next few decades, especially if he is right about his prediction that energy will soon be free. People will no longer have to sacrifice their personal comfort or contentment because of concerns about how much power they are using to run an air conditioner or light up their home office.

“Environmental sustainability might be less of an issue because everything will use renewable energy,” he said. “Whether we are comfortable or not will become much more important.”

Learn more about the device developed by USC researchers through this video: