Trump supporters turn out at a free speech rally at Martin Luther King Jr. Civic Center Park in Berkeley. (Photo/Emily Molli, Sipa images)

Despise a message, but respect the right to share it, says USC free speech scholar

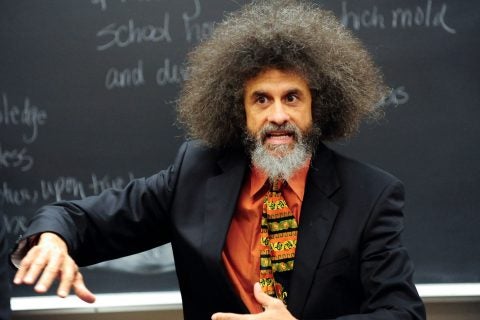

Professor Jody Armour of the USC Gould School of Law won’t back down from upholding the First Amendment: It’s the American way

USC law professor Jody Armour supports the free-speech rights of white supremacists and neo-Nazis to chant and march — even if he finds their messages repugnant.

Are there limits to what people can say and what causes can be championed in the United States? How far can hate speech go in the country? For Armour, the Roy P. Crocker Professor of Law at the USC Gould School of Law, the answers are difficult but clear.

“If white supremacists want to engage in a march that has a political purpose, they should have every right to do so. In a democracy, it’s important that people should be able to unify and rally around different beliefs,” he said. “If they can’t rally around unpopular beliefs, then our democracy is reduced to a mockery.”

Questions over free speech — and how far rights to free speech extend in a polarized society — have hit the headlines in the last year. A rally of white nationalist activists in Charlottesville, Virginia, led to one death and 19 injuries, while far-right and anti-fascist marchers have clashed violently in Oregon and beyond. But legal experts like Armour have been treading carefully and thoughtfully over the matter of free speech, standing up for the tenet they say is essential to democracy.

Free speech creates odd partnerships

From a constitutional law perspective as well as a personal one, Armour supports the free speech rights of opposition groups with whom he disagrees profoundly. He is an African-American professor who has marched in Black Lives Matter rallies and who focuses on freedom of expression in his scholarship. But he points out that the issue of free speech has often created strange partnerships in the history of the country.

In the late 1970s, the American Civil Liberties Union supported the First Amendment rights of neo-Nazis to march in Skokie, Illinois, home to thousands of Holocaust survivors. In 1989, conservative U.S. Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia sided with the majority in supporting the free speech rights of a liberal activist to burn the U.S. flag at the Republican National Convention.

Armour also makes it clear there are limits to free speech as defined by the Supreme Court. The court has ruled against free speech on specific issues relating to the broader public good, including obscenity, “fighting words” (language meant to inflict injury or breach the peace), incitement to violence and solicitation to commit crimes.

Aside from these exceptions for safety, the broad interpretation of First Amendment rights supports his causes just as much as the causes of those who are diametrically opposed to what he believes, he said.

I try to stay balanced in approaching these issues and view it from more than one side.

Jody Armour

“I try to stay balanced in approaching these issues and view it from more than one side,” Armour said. He purposely uses expressions that cross societal norms and boundaries, drawing inspiration from hip-hop culture. “I use the n-word in my scholarship,” he explained, so he understands the chilling effect of barring certain kinds of language.

“I am aware of the danger of any rules or standards we come up with to regulate what we consider to be hateful speech by KKK members or neo-Nazis. I am also aware that those same rules and standards can and will be turned on groups who are more sympathetic to us, groups who are fighting for minorities or marginalized people.”

Protests and political firebrands

As controversial speakers have made the rounds at universities nationwide, arguments over free speech and concerns about safety at these events make news. Polarizing figures on all sides of the political spectrum have been greeted with violent protests and sometimes have been banned from expressing their views.

For Armour, the idea of protesting speakers and ideas is at the core of the free speech movement and the First Amendment. But he believes that protests should not stop political firebrands from speaking at colleges and universities, places of learning and discussion.

“I want to give students leeway to protest and rally against certain types of speakers as long as they don’t keep those speakers from coming to campus,” he said. “I have had people protest my talks because I use the n-word — so I’m speaking about this from personal experience. I have had a picket line at a talk I was giving, but people could cross the picket line and hear me talk.”

Armour said that colleges, universities and similar entities must consider many factors as they consider the complex issues surrounding free speech. Is it done in an educational context? Is it done for political purposes? Is it done for artistic expression? He stresses that there are no easy answers or guidelines that apply to all speech.

“A lot of times ideology oversimplifies things,” he said. “Reality is more complex than ideology.

“We need to be civil in our discourse and understand that other people can have different points of view and reach different conclusions, and only hubris and arrogance can make us think that our solution is the only solution, that where we draw the line is the only place to draw the line.”