Junyan Zhang, left and Tongge Jiang volunteer with the Youthcare program in downtown Los Angeles. (Photo/Nihal Satyadev)

Students get hands-on experience with Alzheimer’s, dementia patients — and give caregivers a break

Youthcare, which recently partnered with the USC Leonard Davis School of Gerontology, gives students valuable training while helping patients’ families

Paul needs to remember to bring pie to Aunt Rose’s party.

“What’s something that would help you remember this?” 18-year-old Charlotte Miller asks him. “What reminds you of your aunt and pie?”

Paul, 81, is quiet for a bit. He thinks. He eventually comes up with a story — going grocery shopping with Aunt Rose and seeing a pie right when they walk in.

Once a week, for a few hours, he practices memory games like these with Miller, a USC freshman. They meet at a clinic in Downtown Los Angeles, a few blocks away from L.A. Live.

It’s part of a program called Youthcare, which recently partnered with the USC Leonard Davis School of Gerontology.

Founded by University of Redlands senior Nihal Satyadev, the social enterprise offers affordable respite care for unpaid family caregivers caring for someone with early to mid-stage Alzheimer’s disease or dementia. Student volunteers, who are trained on the UCLA Longevity Center’s Brain Bootcamp Memory Program, work with clients for a few hours a week, doing memory exercises, they play games like Uno or Connect Four.

Paul, who comes up from Redondo Beach, told Miller he wants to keep up with his wife when they go shopping, but sometimes all the items and aisles confuse him.

His stepson Tim, who brings him to the clinic, said he doesn’t know if Paul has dementia — he hasn’t been diagnosed — but he thinks it’s great to keep his mind active.

Reasons for volunteering

USC students have been enthusiastic, Satyadev said, noting he had to close applications because he was getting so many. He’s trained about 30 students so far. Some of them, including Miller, were motivated to volunteer because of personal experience.

“It’s all because of my grandpa,” she said. “He had early onset when I was in seventh grade and I watched it completely develop. … I saw how Alzheimer’s completely changes someone.”

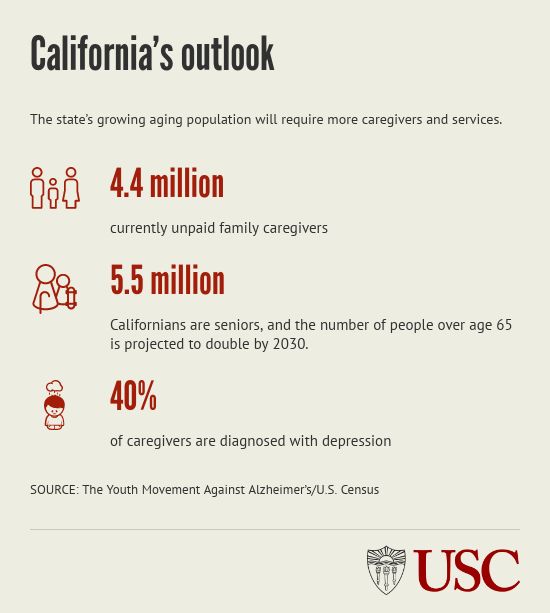

Not only are Alzheimer’s and dementia hard on the 5.1 million Americans living with it, but they take a financial, mental and physical toll on the families caring for them. There are 16.1 million unpaid family caregivers in the U.S. and of those, roughly 40 percent have been diagnosed with depression, according to Satyadev’s organization, The Youth Movement Against Alzheimer’s.

Many family members sacrifice their jobs, retirement or health for caregiving, sometimes not taking a break for months or years. If they do want help, it can be costly — services can run as high as $25 per hour, and Alzheimer’s facilities can cost tens of thousands of dollars a year.

Satyadev, 23, came up with the idea for affordable respite care after seeing his own family struggle when his grandmother, a former ophthalmologist, declined due to the disease.

Look at the numbers

Satyadev looked at the numbers: Alzheimer’s and other dementias currently cost the U.S. $277 billion, expected to jump to $1.1 trillion by 2050.

Satyadev piloted the program at UCLA, thanks to a grant, and said the results were positive.

“What we noticed was with just six hours a week, the overwhelming majority of caregivers said that’s all the break they needed,” Satyadev said.

Eight out of 10 said it also decreased stress.

Satyadev went to dozens of universities for help recruiting volunteers and getting the word out to caregivers, and USC was the first to sign on, he said.

“There’s so many caregivers who don’t have a way to take a break and then, at the same time, we have students and younger generations who may be seeing caregiving and don’t know how to help out. Putting the two together just made a lot of sense,” said Donna Benton, director of the USC Family Caregiver Support Center and an assistant research professor of gerontology.

Although Youthcare is small, Satyadev is hoping to expand. He’s supporting the introduction of a bill, AB 2101, to the state legislature to create a California care corps, similar to Americorps, pairing sponsored students up with unpaid family caregivers. The bill, which his organization wrote, would allow family members to re-enter the workforce, he said.

Lessons outside the classroom

Youthcare gives USC students experience they can’t get in class, Benton said.

“It’s invaluable to learn in this way,” Benton said. “They’re learning skills that if they want to go into any of the health professions — they want to be OTs, PTs, doctors, nurses — they’re going to know what it’s like to care for a person with dementia.”

It also introduces USC students to a job market that’s going to explode in the coming years, as the senior population booms and families shrink, Benton said.

“Over the years, traditionally there have been 12 people to care for older adults. It’s now down to three people to care for older adults. Soon it will be down to 1-to-1,” she said. “There’s already a shortage of care workers. It will be feeding into an automatic job market.”

Miller, who is studying life span health, plans to be a geriatric nurse practitioner.

“I think it definitely solidified my interest in the field,” she said. “I think it helped me realize I want to be hands-on with patients. That’s why I want to be a nurse practitioner, versus a doctor or surgeon.”

Connecting with Paul has become one of the highlights of her week.

“All my friends are like ‘Did you see Paul today?’ and I’m like ‘Yeah, I did,’” she said. “He’s just so sweet.”