Rock climbers learn how to avoid injuries with tips from ‘Climbing Doctor’

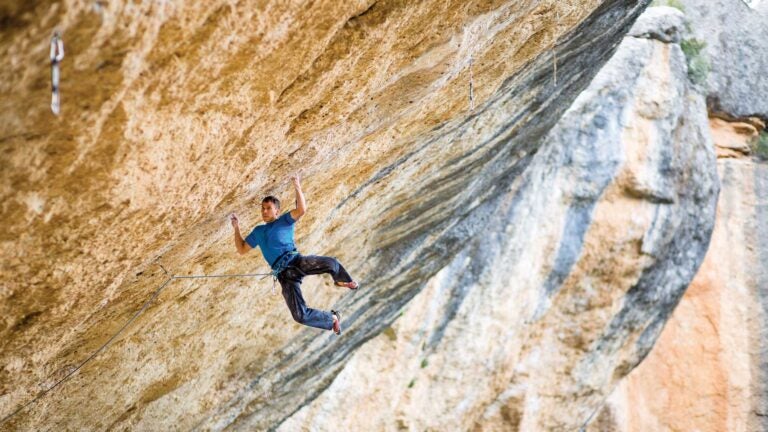

Improper use of the feet or poor mechanics can pose problems for those in the specialized sport, USC alum says

A few years ago, avid rock climber Adam Galper needed a provider who understood his injury.

“I was experiencing a lot of pain on the inside of my elbow,” said Galper, who designs routes for rock-climbing walls. “Every doctor and orthopedic specialist said it was tendonitis and suggested I stop climbing. But they didn’t understand rock climbing or how you use your body.”

After taking six months off, Galper’s injury still didn’t improve. His long search for a provider specializing in rock climbing injuries led to Jared Vagy DPT ’09, who agreed that the problem wasn’t tendonitis.

Vagy looked at all the muscular imbalances occurring in Galper’s body and said it was pretty much an issue of imbalance. The doctor put his patient on a comprehensive plan in which he exercised the opposing part of his forearm, and he was able to climb again.

“After two months,” Galper said, “I was injury-free.”

It’s all about the movement

During the past several years, Vagy has treated and taught more than 1,000 climbers, earning him the moniker “The Climbing Doctor.”

“From a physical therapy perspective, there are very specific things you need to look for in rock climbers that are unique,” Vagy said. “It’s such a specialized sport with a lot of terminology that specifically relates to movement patterns on the wall.”

Vagy speaks from experience. After years of dividing his time between his two passions — physical therapy and rock climbing — he left his job at an orthopedic outpatient clinic in Santa Monica to pursue climbing full-time in South America.

“You wake up in the morning and don’t even need coffee,” he said of his time there. “You just look over the edge and you have 2,000 feet of air right underneath you.”

After six months of alpine and rock climbing, Vagy returned to California to start a movement science fellowship at Kaiser Permanente.

Vagy’s USC degree gave him a strong foundation in clinical reasoning, his residency training solidified his manual skills and the movement science fellowship improved his ability to analyze and treat complex movement patterns such as those in rock climbing.

“I was 100 percent committed to understanding movement, and eventually I started applying those same concepts to rock climbing,” he said.

Proper technique

As a climber and doctor of physical therapy, he has learned, above all, to put an emphasis on climbing with proper movement technique.

I was 100 percent committed to understanding movement, and eventually I started applying those same concepts to rock climbing.

Jared Vagy

“You can perform all of the best injury-prevention exercises, but if you are climbing with poor technique, it’s only a matter of time before you get hurt,” he said.

While more than 40 percent of the injuries Vagy treats involve the wrist, hands or fingers, he said the pain often stems from a patient’s shoulder or lower body.

If he’s looking at a climber with a finger injury, the first thing he does is watch them climb on a wall or watch video of them climbing to see if it’s a technique issue.

“Maybe they’re not using their feet enough and over gripping with their fingers,” he explained.

After that, Vagy looks for poor shoulder blade mechanics.

“But not the same way you look at most patients’ shoulders by taking them through a range of motion in the air,” he said. “On a climber, you have to watch their shoulder in a closed kinetic chain where their arms or their hands are first stabilized on the ground in a crawling position, since this mirrors what they do on a rock wall.”

An ounce of prevention

Vagy also focuses much of his effort on teaching patients proper movement patterns to avoid overuse injuries.

“A good portion of the patients who come to me don’t have any real injuries,” he said. “They want to know how they can become stronger climbers without getting hurt, so they can push their performance to the next level. It’s about injury prevention.”

Vagy recently published Climb Injury-Free, a book that teaches climbers how to prevent injury by correcting faulty movement patterns.

He wrote the book so that medical professionals or physical therapists who aren’t climbers can apply their own movement analysis skills to assess and treat rock climbers.

“The key is understanding the intricacies of the sport — all the different components of movement — then you can start to give climbers different strategies to avoid all these overuse injuries.”

Galper said that Vagy’s unique expertise is worth the commute.

“You can say, ‘I was doing a rose move on pockets the other day, and I was doing a left drop knee and it was super techie footwork,’ and Dr. Vagy knows the exact position your body was in and where it hurts,” Galper said. “I haven’t been injured since I started seeing him.

“The key is understanding the intricacies of the sport … then you can start to give climbers different strategies to avoid all those overuse injuries.”