When Kasia Galazka, a 31-year-old marketing writer in Atlanta, hears a car horn, she feels like she’s been electrocuted. “It’s like my nerves are permanently doused in kerosene, and any loud noise is like throwing a match,” she says. “I don’t talk about it often, because I feel like people would think I'm exaggerating or complaining.” But it turns out Galazka’s not overly sensitive or strangely wired—she just might notice the consequences of unexpected sounds more readily than most.

In reality, unwanted auditory stimuli is like health kryptonite; results from the Environmental Burden of Disease project, presented at the latest World Health Organization Ministerial Conference, declared noise pollution the number-two threat to public health, after air pollution. And the problem, directly related to anxiety, is getting worse—right as nationwide anxiety levels have spiked, largely thanks to the political climate. Cancer, heart disease, obesity and myriad other conditions can be exacerbated by stress. If you’re not down with that, it’s not the best time to be living in a city.

To really understand how noise causes harm, we have to look to our ancestors, who evolved in harsh yet quiet environments. “Loud noise correlated with high-stress events that could damage tissue: thunder, animal roars, screams, or war cries,” says Bart Kosko, Ph.D., a professor of electrical engineering at the University of Southern California and the author of Noise. So, in response to rare but loud threats, we evolved to spurt out adrenalin, cortisol, and other stress hormones—chemicals that jacked up our bodies so we could fight or flee. A constant gush of stress hormones actually restructures the brain, contributing to tumor development, heart disease, respiratory disorders, and more. And of course, our hormonal endocrine systems haven’t had time to learn that car stereos aren’t out to get us. “Today,” Kosko says, “we regularly get similar stress-hormone surges from car alarms, ringing phones, police sirens, leaf blowers, jackhammers, and amplified voices.”

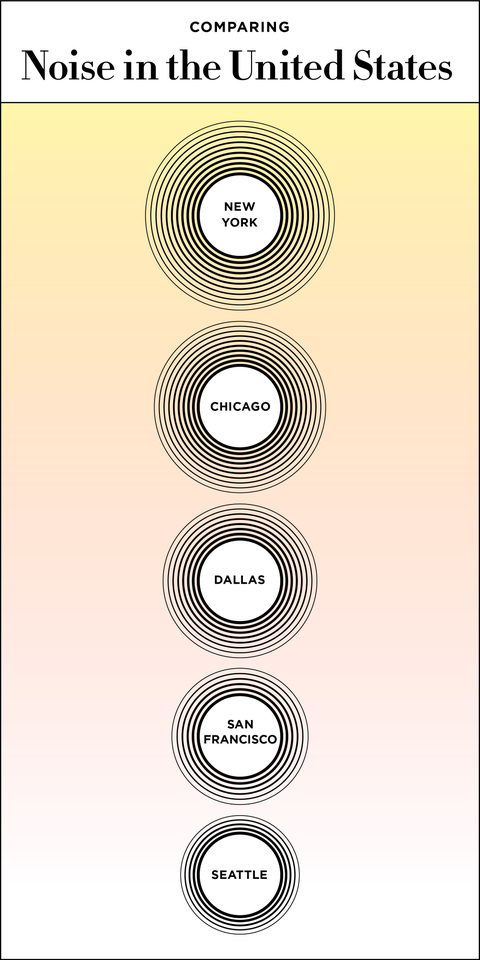

The research backing him up is abundant. A Greek study released last month showed that for each 10-decibel increase in nighttime aircraft noise, the risk of developing hypertension significantly increased. WHO has published data linking environmental noise with cognitive impairment, disturbed sleep, tinnitus, and cardiovascular disease; in Germany alone, traffic noise causes about 1,629 heart attacks each year, one study found. “Even if you don’t have health problems yet, you’ll have diminished quality of life [from noise pollution],” says Arline L. Bronzaft, Ph.D., an environmental psychologist who’s studied the topic for more than three decades. And it’s not a select few dealing with too-loud background dins: About 40 percent of the EU’s population is exposed to street traffic noise at levels exceeding 55 decibels, while anything over 30 can disturb sleep or learning. In New York City, traffic noise in Midtown hovers between 70 and 85 decibels, while in Los Angeles, restaurants consistently clock in between 80 and 90 decibels. (In spring, the Bureau of Transportation Statistics released a noise map of the entire country, which you can check out here.)

There’s evidence it’s worse for women, too. "Women are more field-dependent, meaning they take in the whole picture, while men are more focused on what they’re doing, so they don’t notice what’s in the periphery,” Bronzaft says, adding that on average, more men have hearing loss from working with loud tools or machinery—so they simply can’t hear the dog barking its head off next door. It makes sense, then, that men might have an easier time tuning out background noise, while women can’t help but notice any hubbub. Bronzaft heads up Grow NYC’s Noise Abatement Committee, “so people call me with noise complaints, and if you’d ask if I hear from more women than men, the answer is yes,” she says.

But here’s what’s crazy: Even if you think you’ve adapted to noise—say, you barely notice the train rumbling by your home these days—you’re mistaken. One study in the Journal of Applied Psychology, for example, found that clerical workers in a noisy room were less motivated to complete cognitive tasks and had elevated stress hormone levels, compared to those in a quiet room—but they didn’t feel particularly stressed. “Adaptation is always at a cost,” Bronzaft says. “By dealing with the sounds of the city, you’re using up energy, which is costly to your body.” Galazka knows this firsthand: All her jobs have been in an open office, “and the moment I hear speakerphone or people playing music without headphones, I immediately get upset, because I can just picture my energy dwindling—kind of like in fighting games like Street Fighter where you have a life bar,” she says. The experience of forcing that freakout down is especially depleting, Bronzaft adds. You might be snapping at coworkers or tearing up about the coffee machine being out of order, all because your system has just been beat to hell by your noisy commute.

And even our parents didn’t have it this bad. Cell phones are largely to blame, Kosko says: “Your cell-phone conversation is a signal to you, but it’s noise to those around you.” That’s because a talker in a crowd—e.g., the dude at the table next to you at a packed Starbucks—locks in dialogue with someone who’s not present. “This imposes a type of sonic nuisance on those nearby,” he explains. “It gets worse when several people talk on cell phones: Each speaker must speak louder to maintain the same signal-to-noise ratio as the level of crosstalk noise grows. This leads to the type of upward ratchet of noise that we often hear in crowded restaurants.”

Street noise is getting louder, too, in large part because nobody’s doing anything to stop it. An NYC audit released last month showed that noise complaints more than doubled in the last five years; thank increased construction, the removal of “NO HONKING” signs in 2013 (transportation officials called them “visual clutter”), too few DEP inspectors to look into potential violations, and less attention paid to train and bus maintenance, which leads to squealing, grinding equipment, Bronzaft says. And when making over the EPA’s website, the current administration downgraded noise pollution to a subset of air pollution (diminishing the federal control of noise even further), with remarkably few resources or links to information for visitors. “The divide between research and policy is what’s upsetting to me,” Bronzaft says. “Noise is harmful to health, it’s harmful to children’s learning, and it diminishes quality of life—the evidence is strong. What we haven’t done is ameliorate it, even though we know how to. Do you really think it’s rocket science to lessen the noise in our lives?”

Without our government dampening the day-to-day hubbub, some people have turned to pricey, private firms that offer much-needed quiet. Sensory-deprivation tanks, embraced by the New Age movement in the ‘70s and ‘80s, are seeing a resurgence stateside; even the New England Patriots have the pods installed in their locker room. Big-ticket “digital detox” packages, free from the beeps and rings of modern gadgets, are proliferating across luxury resorts, from Cape Cod’s Chatham Bars Inn to Playa Del Carmen’s Grand Velas Riviera Maya; at the W Maldives, for example, an escape to Gaathfushi deserted island starts at $1,500 per person for a half-day visit. And in Uganda’s remote Bwindi Impenetrable National Park, a swath of jungle far from any metropolitan din, lodge directors were surprised to find that some guests treasure the hushed noise level almost as much as the safari experience (it’s one of the only places in the world where visitors can come within feet of wild gorillas). “We’ve had many clients comment on how the peacefulness and general atmosphere of the area helped their medical conditions,” says Barry Gotch, managing director of Mahogany Springs Lodge. “High blood pressure, palpitations, and other conditions apparently disappear during their trip.” While he never expected return visitors (seeing the gorillas is, after all, a once-in-a-lifetime experience), about one in twenty guests come back for the peace and quiet, he says.

And these noise detoxes aren’t all hype. “I recommend noise fasts and often take them myself in the mountains or desert,” Kosko says. “There’s an immediate drop in stress and a fresh sense of wellbeing—perhaps as we return to our old hunter-gatherer equilibrium with the quiet environment.” The deep quiet also spurs creativity and helps him work through problems. “Alas, it always ends badly with the commute back to the noisy city,” he adds; much like the end of Dry January or a healthy-eating “cleanse,” no quick fix can outweigh your daily norm. “While vacations serve to relax us from the day to day stresses,” Bronzaft says, “living in noisy cities adversely affects our quality of life, and in the long run, we need to lessen the din in our environments.”

There’s even a sought-after accreditation now for consumers interested in buying quiet, high-quality appliances and tools. Since its debut in 2012, Quiet Mark, an international program associated with the UK Noise Abatement Society, has worked with more than 70 brands, including Electrolux, Bosch , Dyson, Interface, Logitech, and Samsung, to prioritize noise reduction in their designs. “People immediately took to the idea of a clear mark of approval for quiet products of all types,” says Poppy Szkiler, Quiet Mark’s founder. “Given the choice, we’ve found that consumers will automatically opt for a quieter product if performance is unaffected.” (Szkiler is also an executive producer of In Pursuit of Silence, a documentary on our relationship with silence and noise that made its US theatrical debut on June 23.)

Even if a kitchen renovation (or gadget-free five-star escape) isn’t in your future, we can all take steps to protect ourselves from noise pollution’s stress-y effects. If you’re moving, finding a quiet home is key, Bronzaft says: “Come and see it in the evening. Sit still and really listen. Check for double-paned windows and noisy neighbors.” In your existing home, hang muffling drapes. And be careful with headphones and earbuds. “Injecting sonic energy directly into the ear canal can cause irreversible hearing loss,” Kosko warns. If you’re using tunes to drown out the sounds of your open office, keep the volume low. At night, consider a white-noise machine or fan to mask noise.

And of course, as a denizen of the earth, you can benevolently not make your neighbors’ lives miserable: Turn the TV and stereo down, especially at night, and avoid blabbing into your phone while others are trapped around you (we’re looking at you, obnoxious Uber Pool car-sharer). Step into your stilettos at the door so they aren’t clicking against your downstairs neighbors’ ceiling, and don’t ever be that headphoneless person cranking up her phone’s volume on the subway, in an airport, or at the gym.

For Galazka, white noise and earplugs helped her focus and catch some sleep, but ultimately, moving from New York City to a quiet part of Atlanta let her finally find peace and quiet. “I learned that you don't have to live in misery,” she says. “I finally left the city for various reasons, but one of them was definitely the noise level. I realized I couldn't change how I'm wired, and coming to terms with leaving a dream city was really difficult for me. And honestly, I miss it all the time. But the city and its mess of glorious noise will always be there, and I take comfort in that, too.”