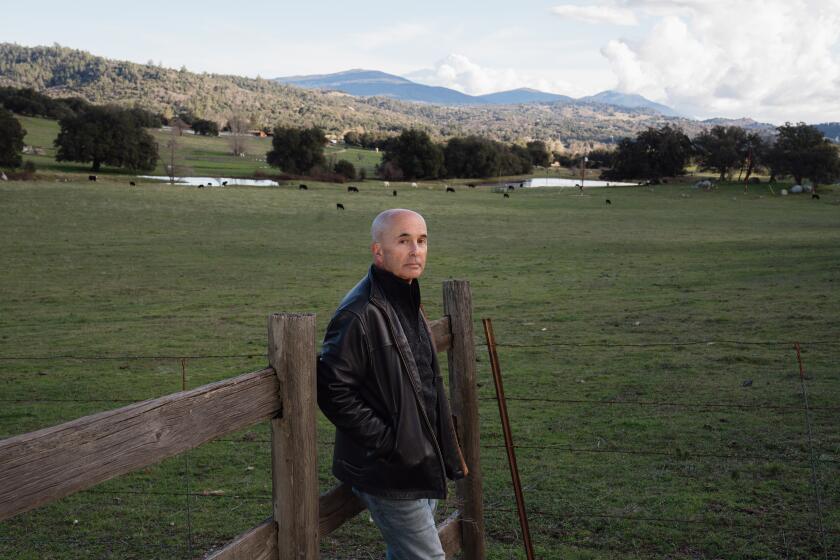

Poet Laureate Dana Gioia talks rhyme (and reason) as he heads to San Diego

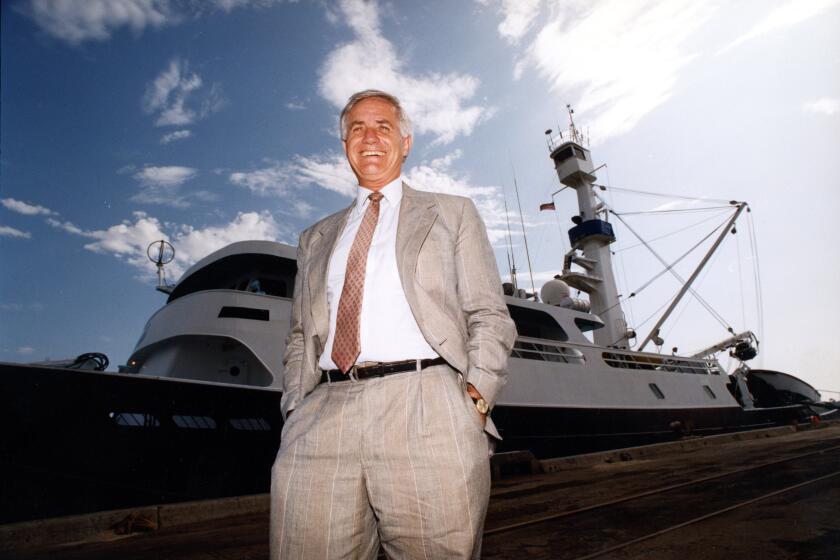

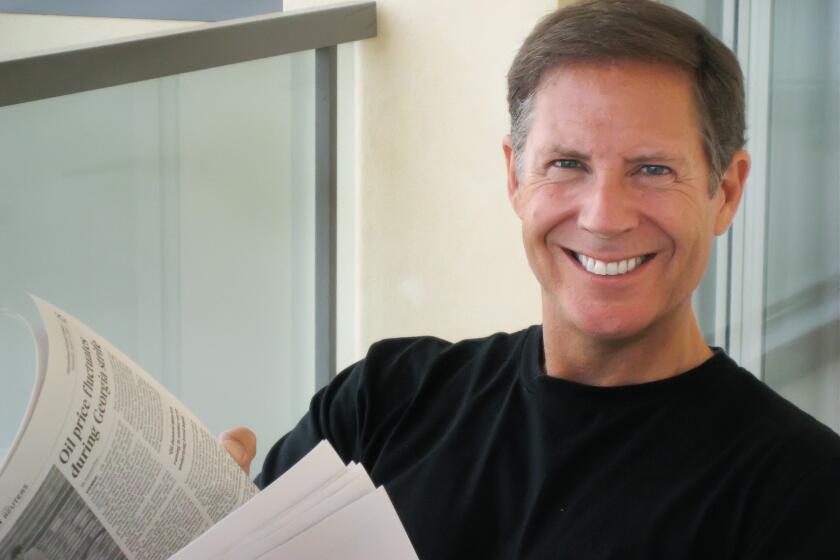

Twenty-five years ago, Dana Gioia wrote a book called “Can Poetry Matter?” that spurred an ongoing debate about the role of the art form in American life.

He went on to head the National Endowment for the Arts for six years and is now California’s poet laureate, where he’s on a mission to visit all 58 counties and nurture an appreciation for what he calls “the conversation of the spirit.”

A much-anthologized poet himself, his newest book is “99 Poems,” a career retrospective that also includes a dozen new pieces.

Gioia (pronounced joy-uh) splits his time between Sonoma County and Los Angeles, where he is a professor of poetry and popular culture at the University of Southern California.

He’ll be at the San Diego Central Library for a reading and public discussion on Monday at 6 p.m. We caught up with him by phone at his physical therapist’s office, where he was having a finger taped.

Q: Is it a typing injury?

A: At my age (he’s 66), you have to be held together by tape. It’s pretty sad. You spend your whole life writing and keyboarding and it catches up with you.

Q: What do you remember about the first poem you ever loved?

A: That’s a fairly early memory for me because my mother used to recite poems. She was a working-class Mexican woman, not a lot of education, but she had gone to a school where they had to memorize poems. As a kid, my earliest memory of poetry is her reciting Edgar Allan Poe’s “Annabel Lee.”

I think that experience was really quite average for most people in a working-class household. It wasn’t like a literary life where people are saturated into it, but it was one of the things, like playing cards and cooking, that we did. Reciting or reading the occasional poem was part of the ordinary pleasures of life.

Q: How did that upbringing influence you?

A: I think it’s one of the reasons why I’ve always resisted the elitism that one so commonly finds in the poetry world. I was the first person in my family to ever go to college. I went to Stanford and then went to Harvard, which are very fine schools, but very elitist, and there was an assumption at both places that poetry was something only the intellectual could do. It was just too difficult for ordinary people. That never made any sense to me.

Q: How old were you when you first started writing poetry?

A: My first poem was written in fourth grade because the teacher asked us to write one. Mine I think was really quite terrible. But that’s how one begins.

In high school I wrote a lot of bad, self-pitying poetry. “Woe is me, nobody appreciates me.” I did not think I would be a poet. When I was in high school, I knew I wanted to do something intellectual and artsy, but I thought I was going to be a musician. Poetry kind of snuck up on me and I was surprised when the muse grabbed me at the age of 20.

Q: What keeps you writing it these days?

A: That’s a good question because when you’re young you’re full of all kinds of dreams and passions. I think at this point I see poetry as a sort of conversation of the spirit that’s existed for all of human history. It goes all the way back to the time of Homer and before. The conversation of poetry predates writing and that itself has become fascinating to me.

My first decent poem was probably in my early 20s. I’m 66 now. I have a number of poems that have become well-known and every week I get strangers writing me because they are responding to an essay or a poem I’ve written. And it gives you a different perspective because you realize you are part of this conversation that’s greater than you are.

So the reason I continue is that having spent my entire adult life writing and reading poetry, I’ve grown fascinated by the human possibilities of the art. I hope to make an enduring contribution but I also find a sort of spiritual alertness by practicing poetry. It keeps me aware of my own life and the language which I share with other people.

Q: Tell me about the project to visit all the counties in the state.

A: I’m a native Californian but I still haven’t seen half the state. I’m going to all of these places I’ve either never seen or simply driven through. And in each case I’m meeting people.

Now, San Diego is different. My brother used to live there. My college girlfriend was from San Diego. But everywhere I go in California, I have a different series of conversations about poetry and about the state and it has transformed and enlarged my whole sense of the place where I live. I’m not sure I’ve had any impact on the audiences, but for me it’s been an enlightenment.

An interesting thing about giving a well-attended poetry reading is that you have an audience that’s not used to being together and they are surprised to see how many other people share their interests and they are engaged to listen to what people are saying. So one of the most important things I do is gather an audience together and have it hear itself talk.

Q: How has the conversation shifted in the years since “Can Poetry Matter?” was published?

A: Most of the trends that I talked about 25 years ago are still present. Poetry is even more isolated in the university. It’s even more absent in the mass media. Poetry criticism is even more remote from the needs of ordinary readers. The one significant change has been that outside the university and the mass media, there’s been an enormous amount of local organizing to create poetry events, presses, instruction and a kind of participatory culture.

It comes down to something really simple. People don’t necessarily like to read poetry, but most people love to hear a good poem well-recited. So the major trend that’s happened is that the energy of poetry now happens when it’s taken off the page and spoken. This trend originated and continues almost entirely outside English departments. So it’s a kind of populist energy in poetry versus an elitist trend. The whole culture is moving from the book to the screen or the speaker.

Q: Let me lob one into your wheelhouse: Why is poetry important and worth saving?

A: Poetry is the most ancient art. It goes back to a time before writing when we made art with our human bodies. We danced, we sang, we recited. And poetry survives from that ancient time because it is the most concise, memorable and powerful way we have of using words.

“99 Poems: New & Selected,” by Dana Gioia, Graywolf Press, 208 pages

john.wilkens@sduniontribune.com; (619) 293-2236

Get U-T Arts & Culture on Thursdays

A San Diego insider’s look at what talented artists are bringing to the stage, screen, galleries and more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the San Diego Union-Tribune.