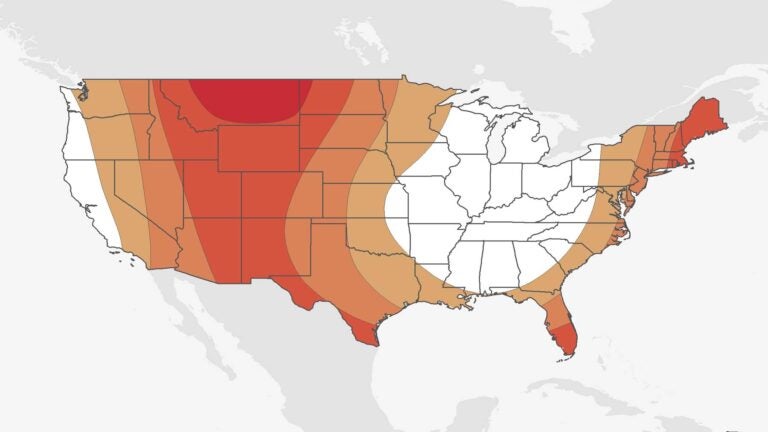

A forecast for July shows areas that have a chance of being warmer than usual; the deeper reds indicate a higher probability of increased temperatures. (Illustration/Courtesy of NOAA)

As temps soar, USC experts have hot ideas on what it means for us

Sweltering conditions can have an effect on flights, pollution and your health

The National Weather Service forecasts the possibility for record-high temps in some areas over the weekend, as well as thunderstorms. High temperatures are more than just a good excuse to hit the beach — they can impact flight plans, our well-being and the environment.

“Weather is an essential element to be considered in the planning and decision-making process that results in a safe flight. This is especially true with regard to extreme weather,” said Thomas Anthony, director of the Aviation Safety & Security Program at the USC Viterbi School of Engineering.

“Weather conditions such as thunderstorms, reduced visibility due to fog and precipitation, strong crosswinds, extreme cold and extreme heat all require consideration and mitigation in terms of an aircraft’s certificated performance in order to maintain an acceptable level of safety,” said Anthony, an expert on the grounding of flights in desert areas like Phoenix.

Temperatures can be much hotter downtown. Why’s that?

“The urban heat island effect describes a phenomenon where the air temperatures inside an urban city are higher than the air temperatures in the surrounding areas,” said George Ban-Weiss, an assistant professor of civil and environmental engineering at the USC Viterbi Ban-Weiss who has conducted research on how heat varies in Southern California in hot and cool islands, especially in the month of July.

“The urban heat island effect occurs for three primary reasons. The first is that cities have a lot of dark materials like dark pavements and dark roofs and those dark materials absorb a lot of sunlight,” he said.

“Another reason is that cities generally don’t have a whole lot of vegetation. Vegetation transpires and evaporates water and thus the evaporative cooling can act as sort of an air conditioner.

“The last reason is that cities have a lot of thermally massive materials and these materials can absorb the heat during the day. They store it and then at night they release the heat, so that can lead to increased nighttime temperatures.”

Rising heat threatens well-being

“Body dehydration that occurs with heat stress can produce significant deterioration in cognitive functioning. Heat waves have been associated with increases in hospital admissions for mental health disorders, including dementia; mood [affective] disorders; neurotic, stress-related and somatoform disorders; disorders of psychological development; and senility,” according to Lawrence Palinkas, a professor of social work, anthropology and preventive medicine at the USC Suzanne Dworak-Peck School of Social Work.

“Some patients with mental illness are especially susceptible to heat. Dementia is a risk factor for hospitalization and death during heat waves. Medications may interfere with temperature regulation or even directly cause hyperthermia,” he explained.

“Heat suppresses the thyroid hormone, which causes energy drain, while also stimulating growth hormone and a closely related protein hormone called prolactin, which cause lethargy. This also inhibits the effects of dopamine, a chemical in the brain that is associated with positive feelings.

“Suicide rates vary with weather, rising with high temperatures, suggesting potential climate change also impacts depression and other mental illnesses.”

Pollution threat rises with the heat

“The stagnant weather conditions that often accompany high-heat events can also set into motion a meteorological condition known as a temperature inversion. Think of it as a pot cover on something heating on the stove,” said Ed Avol, a professor in the Environmental Health Division of the Department of Preventive Medicine at the Keck School of Medicine of USC.

“Even though hot air rises, regional vehicle and industry emissions are prevented from dispersing vertically up into the atmosphere by a thermal ‘pot cover’ over the area, so pollution builds and builds under the ‘pot cover’ until a breeze develops to blow it horizontally away or the ‘pot cover’ is eventually removed [by atmospheric cooling].

“Under these conditions, think about ways to reduce your thermal stress: Drink plenty of water, try to avoid heavy exercise during hotter times of the day, wear lighter-colored clothing to better reflect solar radiation, wear a cap, sunglasses and use sunscreen,” said Avol, who has served on several expert panels to review national air quality standards, ensuring that health is a chief consideration in urban planning issues such as freeway expansions and the increased cargo goods movement.

No cover from heat exposure

“The urban forest is our first line of defense against extreme summer temperatures. Cities are already warmer than surrounding countrysides because of their lack of vegetation, and the shade of trees has measurable benefits for local temperatures,” said Travis Longcore, an assistant professor of architecture, spatial sciences and biological sciences with the Spatial Sciences Institute at the USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences.

Longcore studies how reduction in tree cover is contributing to warming through reduced shade, as well as the impact of warming on different types of ecosystems. In a recent study, he and his colleagues found that tree cover in Los Angeles during the 2000s fell by as much as 55 percent.

“Unfortunately, our research has shown that trees are being cut down in single-family neighborhoods across the Los Angeles basin to make way for bigger houses and more hardscape at a time when more tree cover is what is needed to adapt to an increasing frequency of heat waves.”