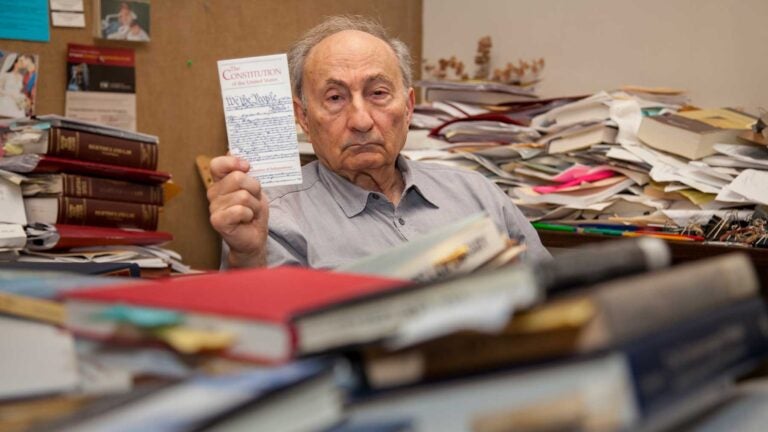

Michael Shapiro likes getting to the bottom of questions on the Constitution. (Photo/Brett Van Ort)

Constitutional expert speaks his mind on the tough questions

USC Gould Professor Michael Shapiro sees bioethics and constitutional law as ‘mutually illuminating’

In the office of Michael H. Shapiro, piles of paper cover almost every horizontal surface.

“I’ve got stuff on the floor back there from the 1994 earthquake,” the USC Gould School of Law professor said.

Shapiro, the Dorothy W. Nelson Professor of Law and a specialist in bioethics and in constitutional law, enjoys analyzing the issues that advances in the biomedical sciences generate. Take surrogate motherhood: If a woman gives birth to a child created in vitro from another woman’s egg, who is the mother?

Or consider a hypothetical scenario that Shapiro first laid out in a landmark 1974 article, “Who Merits Merit?”: If we had the biotechnological capability to significantly increase a person’s IQ, whom should we target? Would it be the smartest people who might then achieve great things for the benefit of all? Or would it be those with the largest intellectual deficits?

Shapiro approaches such conundrums as a consummate, all-around scholar. Passionate about the sciences from early on, he originally studied physics, but went on to earn two philosophy degrees from UCLA and a JD from the University of Chicago Law School.

He worked as an attorney in private practice and with nonprofits, and taught at Yale University and UCLA. Having first lectured at USC Gould in 1966, he joined the faculty again in 1970.

Creative thinking

At the time, USC Gould was among the pioneers in using an interdisciplinary approach to the law. Shapiro, said Vice Dean Alexander Capron, exemplified that approach: “He was dipping into the medical and cognitive sciences and genetics, and thinking about where the newly developed capabilities might take us.”

Shapiro, who Capron called “a creative, out-of-the-box thinker,” has a reputation for speaking his mind. He’ll tell students that they are wrong about something or that a question “isn’t entirely sound as formulated.”

But hidden underneath the gruffness is a softer side. The professor can be candid about his own foibles. And tangents he goes off on while discussing bioethical matters reveal broad interests: Black holes and gravity pop up, as do the stock market, Moby Dick (“boring”) and the TV series Gilmore Girls (“very clever”).

He generously shares his time and expertise with others. One admirer, Richard Barton ’81, who practices health care law with the Procopio firm in San Diego, speaks of Shapiro as “a kind and brilliant man.” He keeps an open-door policy for students, and he’ll patiently explain to a layperson how bioethics and constitutional law fit together or why bioethical questions vex us to begin with.

It’s like this

Shapiro’s theory in a nutshell is this: When we fragment and reassemble basic life processes such as reproduction, death and dying — when we revise nature — long-held norms no longer seem to apply. New categories like a three-parent child “make our minds explode.”

If you really want to understand bioethics, you have to look at constitutional law because the Constitution embeds our moral values.

Michael Shapiro

The Constitution leads us out of our discomfort, he said: “If you really want to understand bioethics, you have to look at constitutional law because the Constitution embeds our moral values.” Bioethical questions, in turn, are “a superb tool” for testing the meaning and the application of constitutional law. The two areas overlap. They are “mutually illuminating.”

Shapiro is working on a multi-volume book about bioethics and the Constitution. His co-author, Roy G. Spece Jr. ’72, a former student who teaches bioethics and law and constitutional law at the University of Arizona, said that Shapiro inspires him to keep learning and “to be my absolute best.”

Phrased differently: Shapiro holds high expectations for his students.

“When they are done here,” he said, “they must be able to analyze a case and argue it to anyone — including another lawyer, the Supreme Court and the person on the street. This means that when we go over the law, we have to understand the whole process from top to bottom. You don’t really understand what an apple is until you eat it, pull it apart. We eat cases. Without destroying them. A neat trick only lawyers can do.”