We are all – or nearly all – slaves to technology. Think about how many times you consult Google every day. Consider the role that social media like Facebook and Twitter play in your lives. And when you buy a book, or countless other items, it’s increasingly likely that you purchased it from Amazon.

These brand names have come to define our lives in ways that have crept up on us so that now we can’t imagine being without them. But has their influence grown too large? For all the futuristic idealism that marked their beginning, have they turned into rampant capitalist monopolies that are indifferent to the damage they wreak, and contemptuous of the governments whose taxes they avoid?

Yes, is the resounding answer according to Jonathan Taplin, a former rock tour manager and film producer turned academic specialising in digital media. He has written a book called Move Fast and Break Things that’s a scathing indictment of these tech companies’ greed and arrogance.

The title comes from Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg – it was his credo for startups. “Unless you are breaking stuff,” he explained, “you are not moving fast enough.”

And Facebook and its fellow internet giants have certainly broken a lot. Taplin initially intended to write a book about how the music industry, or more specifically many musicians, had been broken by first Napster, the file-sharing company set up by Sean Parker, and then the various companies, including YouTube (now owned by Google), that followed in its destructive wake.

“My obsession at the beginning,” he tells me in his central London hotel, “was I had some friends who were musicians who got completely damaged by this.”

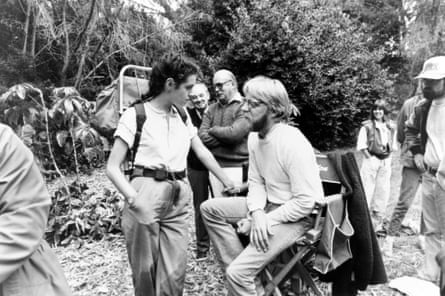

Taplin started out as a young man working as Bob Dylan and the Band’s tour manager. Now 69, he looks remarkably youthful, with a disarmingly easy manner that has taken him to the top in several professions.

One of the members of the Band was the drummer Levon Helm. For a long time after the group split up, he would make about $100,000 a year on royalties from old records.

“He made a living,” says Taplin. “Then Napster hit in 2000 and he got throat cancer the same year and it made his life a living hell.”

Taplin wanted to understand how people like Helm, creators of great and lasting music, came to penury, while the companies that were exploiting their music made billions.

“I thought of it as a culture war,” he says. “But once I came to look into it I realised that it was really an economic war.”

The turning point in his research was last year’s American presidential campaign.

“I began to realise how much effect Facebook had on the news in terms of the number of people coming to it through Facebook. And I saw how malicious forces could play that open platform to push stuff that wasn’t even close to the truth.”

When Zuckerberg succumbed to pressure from Fox News and Breitbart, the two big rightwing media outlets, and removed editors from news selection, Taplin says it swung the election Trump’s way.

“Literally the next day, the fake news business took off.”

He shows me a chart with two graph lines – one of fake news stories going up rapidly in currency and the other of mainstream news stories plummeting. But if Facebook could wield this kind of influence, what safeguards and codes of conduct was it obliged to maintain? The answer was almost none.

Where old media had guidelines they were at least meant to follow, Facebook had set itself up as a neutral platform that did not discriminate between good and bad or true and false. It was not responsible for content. It didn’t produce it. Similarly, Google didn’t produce content either.

These two vast media giants had come to prominence under the principle that “information wants to be free”.

That was the future, and one trumpeted by an unholy alliance of compliant politicians, gullible futurologists, naive old media desperate to get with the new, hackers, pirates, libertarians, internet anarchists, and consumers who just liked free stuff.

There was an exciting iconoclasm to this digital transformation. As Peter Thiel, co-founder of PayPal and original investor in Facebook, and Larry Page, co-founder of Google, liked to say: don’t ask permission. Just do it and deal with the reaction when you’re in a stronger position to fight your corner. Both Thiel and Page are adherents of the Russian-American libertarian philosopher and novelist Ayn Rand, whose defining quotation was: “Who will stop me?”

But of course there is no such thing as free information. Someone has to pay for it. Just not Google or Facebook. And with the free information that they were using from elsewhere, these twin behemoths built themselves into the biggest advertising sales companies the world has ever seen. From 2000 to 2014, US advertising revenue fell from $65.8bn to $23.6bn, Taplin documents in his book. And between 2007 and 2013, UK ad revenues went from $4.7bn to $2.6bn. But from 2003 to 2015, Google’s revenue went from $1.5bn to an astronomical $74.5bn.

In other words, the companies supplying the “free” information were devastated, while those exploiting it were massively rewarded. But isn’t that just the way of history? Aren’t those who complain just modern versions of the wagon wheel manufacturers decrying the arrival of the automobile?

“I call those people techno determinists,” says Taplin. “They believe they’re the smartest cats in the room and they know where the world is going.”

But, he insists, there is nothing inevitable about it. The tech giants have benefited from legislation that protects them from the scrutiny and responsibility to which their old media competitors must conform.

“They have safe harbour protection,” says Taplin, “which means that nobody can sue them for putting up content that offends them. In other words, where a television station would have its licence revoked if it filmed killing someone live and put it out, Facebook can do that and nothing happens.”

He believes that we, and more importantly our governments, have bought into the idea that new media is different. It can’t be contained and regulated, and any attempt to do so is derided as “censorship”. But as a consequence these companies have become vast monopolies that dominate to the exclusion of everyone else.

They are not examples of free competition, but its sworn enemies.

What’s more, they’ve developed a variant of business practice that’s been termed “surveillance capitalism”. The genius of the internet giants is that they make their users complicit in their commercial exploitation. They data-mine users who, through their every action, reveal their commodified identity.

“So you’re the raw material in the product they manufacture and then sell to advertisers,” says Taplin. “Amazon now puts a microphone in your house called Alexa. That microphone is always on. It’s recording endless nothing, but maybe you’ll say, ‘Oh, we need diapers”, and the next time you [go online] there’s an ad for diapers.”

Everything is fiendishly geared towards ad sales. So there is no discrimination, no quality control other than quantity response.

Taplin writes that, for Google and Facebook, “the difference between the supreme artistry of a Martin Scorsese short film and an amateur cat video lies only in the number of views that can be sold to advertisers.”

Still, it doesn’t matter how clear and sharp the diagnosis of the situation is, the fact remains that consumers benefit. There will be people who will walk to their local bookshop and order a book that will arrive a couple of days later, for more money, and which they have to collect, but they are in the minority. There are people who will prefer a much more expensive black cab driven by a knowledgable driver, but again there is a reason why Uber is such a resounding success: it’s cheaper.

Consumers, however, are also employees. And in the dreams of people like Thiel, there will be significantly fewer employees in the future, as they’re replaced by robots with artificial intelligence. Will consumers only begin to recognise the truth of their condition when they start losing their jobs?

“That may be,” says Taplin, “but if we have to wait until we’re in a Blade Runner world, then it will be too late, from my point of view. So the question is: when does the resistance begin? In the States at least, the resistance began with the musicians who said they were tired of having YouTube put their music on their servers for free when they didn’t want it there. So we’re going to work with whoever we can to get a law passed that when music is taken down, it has to stay down.”

That’s a benefit to some musicians, of course, but it’s hardly a revolution. And it certainly won’t challenge the power of the internet’s biggest companies.

“In all honesty,” says Taplin, “these companies are what economists call natural monopolies. There’s no point in you and I forming a new search engine in competition with Google. We’d blow all our money and then go away. The same with Facebook. These companies are not going to get replaced.”

He hopes that the European Commissioner for Competition is less beholden to the tech giants than the American antitrust authorities, which he feels have rolled over and allowed them to do what they want. What’s critical now, he says, is that they’re not allowed to get any bigger.

“Neither Spotify nor Snapchat should be allowed to be bought by one of these companies,” says Taplin. “The problem is these guys are so smart and the politicians are so dim-witted about it.”

Taplin has an extraordinary career behind him. After working with Dylan while still in college, and then becoming the tour manager for the Band, he helped organise the Concert for Bangladesh with George Harrison.

After that, he took off for Hollywood and met a young film-maker who’d been the editor on the film of Woodstock, the concert. Martin Scorsese had a script he wanted to film and Taplin agreed to produce it. The film was Mean Streets, one of the key movies of the new American cinema of the 1970s. He went on to produce several other films, including The Last Waltz and Gus Van Sant’s To Die For, before going to Merrill Lynch as vice president for media mergers and acquisitions. That was a major career shift, I say.

“At the end of the day,” he replies, “I didn’t like it. Too much shady business going on.”

He then founded Intertainer, the first ever internet film-on-demand service. When one of Intertainer’s shareholders, Sony, launched a similar service with several other major film studios, Taplin filed an antitrust suit. His career in Hollywood was over.

Then came an invitation to teach at the University of Southern California’s Annenberg Innovation Lab, a job he accepted because, he says, “I could afford to because I won the antitrust suit”.

And now he’s taking on the biggest companies in the world. Is he concerned that he’s made himself a public enemy of people like Larry Page and Jeff Bezos, not to mention Peter Thiel, who bankrolled a legal suit that bankrupted Gawker because it had outed him as gay?

“A little bit, yeah. I saw what Thiel did to Gawker. I find it ironic that someone who claims to be for liberty and has said that privacy has no role in the future will sue someone out of business for offending his privacy. But the fun thing is I’m almost 70. There’s nothing really they can do to me.” He breaks into a big smile and adds without exaggeration: “I don’t mind playing the role of muckraker.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion