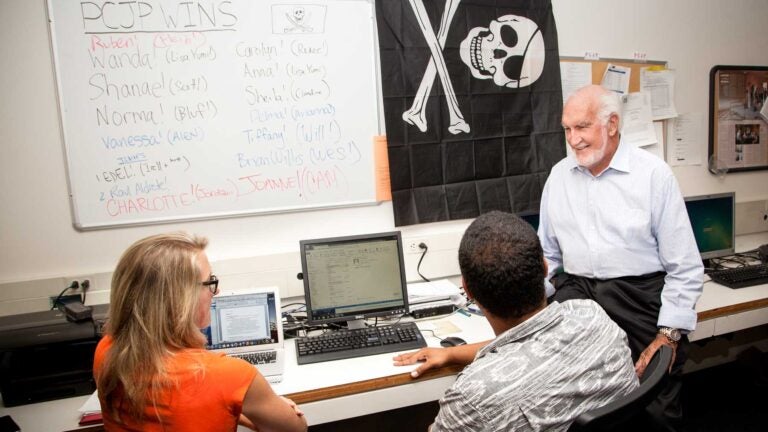

Michael Brennan, right, at work in the Post-Conviction Justice Project office, where the pirate flag goes up when a client is released from prison. (Photo/Mikel Healey)

USC law school’s Post-Conviction Justice Project fights the good fight — and frees clients

The high-stakes work of the 30-year-old program helps people serving life sentences

For dozens of people serving wrongly serving life sentences or whose rights were violated, the Post-Conviction Justice Project at USC has been life-changing. That’s what has kept co-director Michael Brennan going for more than 30 years.

The USC Gould School of Law professor has mentored hundreds of fledgling lawyers. He has taught them to be forceful when arguing in court, diligent when filing habeas petitions and sensitive when meeting fretful clients. (A habeas petition proceeds as a civil action against the state agent — usually a warden — who holds the defendant in custody.)

Regardless of where they are today, many alumni say they are forever bound by their involvement with Brennan and the USC Gould Post-Conviction Justice Project. As law students, they have represented hundreds of clients — from juvenile offenders serving life terms to women convicted of defending themselves against abusers. Brennan’s work with the Justice Project has fueled him for the past 33 years.

“I think I’ve stuck with this so long because the work is so interesting,” he said. “The students change, the cases change and the processes change. It never gets old or boring.”

A steady hand

Under the direction of Brennan and co-director Heidi Rummel, the Justice Project offers hands-on legal training to USC law students. The Trojans represent clients at parole hearings and in state and federal habeas petitions and appeals challenging violations of constitutional rights.

The students have also transformed the legal landscape in California by fighting for new legislation in Sacramento, taking cases to the California Supreme Court and vigorously representings clients who could not afford attorneys.

Although the stakes can be high for the project’s clients, Brennan rarely gets rattled. He’s known for his steady manner and patience.

Mike’s even-keeled devotion to his students’ development … is something I will always appreciate.

Adam Reich

“Mike’s even-keeled devotion to his students’ development, along with his willingness to allow his students to own their cases and take risks, is something I will always appreciate,” says Adam Reich ’09, an attorney with Paul Hastings in Los Angeles.

From legal aid to public defender

Brennan graduated from the law school at the University of California, Berkeley in the mid-1960s, just as the Vietnam protests were raging. His career took him from the California Rural Legal Assistance Fund to the federal public defender’s office in Los Angeles and to Emory University, where he was a clinical law professor. He was later an attorney and partner at a private law firm in L.A., but found civil practice dull and unfulfilling.

“I called a friend and said ‘I’ve got to do something else’,” Brennan recalled. “He told me that USC law was looking for a clinical professor to help supervise its [Post-Conviction Justice Project]. I got the job.”

Brennan’s students initially represented male prisoners at the Federal Correctional Institution on Terminal Island. But in the early 1990s, the project also began working with clients serving life-term sentences for murder at the California Institution for Women. Many of them had been convicted of first-degree murder for killing their abusers.

Word spread among the women at the institution, and Justice Project’s caseload grew exponentially. Still, it was a struggle. Few governors were releasing life-term inmates, not even women who were survivors of abuse, despite a new law allowing expert testimony on battered women syndrome.

The momentum shifted in 2008 when the Justice Project scored a victory in the California Supreme Court. USC law students argued that longtime client Sandra Davis Lawrence’s due process rights had been violated by the governor’s decision to reverse her fifth grant of parole, after she had been fully rehabilitated. The court agreed, opening the door to judicial review of arbitrary denials of parole for inmates who no longer pose a danger to society.

Sudden impact

The ruling’s impact was dramatic. At the time of the Lawrence decision, 21 Justice Project clients had been released from prison in nearly two decades. In the next five years, more than 100 clients were released through grants of parole or successful habeas challenges.

The project has continued to expand under Rummel and Brennan. Since 2010, it represents juveniles serving adult life sentences, and it helped draft and pass the California Fair Sentencing for Youth Act, which took effect in 2013.

“If you told me 30 years ago that I would still be here, I’d think you were crazy,” Brennan said. “But this is what keeps me going.”