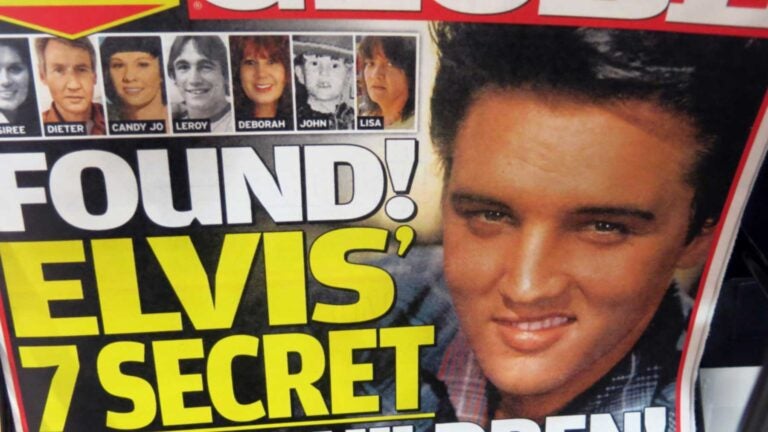

Fake news might not be reserved for tabloids anymore. (Photo/torbakhopper)

Who’s to blame for fake news and what can be done about it?

USC experts weigh in on the internet-driven phenomenon that has quickly changed the way we look at just about everything

No longer relegated to the covers of tabloids in the grocery store aisle, fake news has become big business with easy distribution via social media and the internet. Can and should it be stopped? Who is responsible? USC experts discuss the implications of fake news on law, politics and society.

‘Disinformation’ ? defamation

“Disinformation or ‘disinfo’ are news stories that are fake but look real based upon the quality of the writing.

“Disinfo deserves First Amendment protection because it is speech – even if it is wrong. If we were punished every time we said something wrong, none of us would be allowed to speak. But that demonstrates why the First Amendment is so important – even wrong speech can be said without fear of reprisal.

“The second issue is whether disinfo constitutes defamation. That depends on the circumstances and whether someone’s reputation has been injured. An otherwise creditable news organization can get itself sued for not doing an adequate investigation of the facts before running the story; and, by lending its credibility to a bad story, probably deserves to be sued.”

MICHAEL OVERING

Adjunct professor at the USC Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism

Ethical standards for internet ‘broadcasters’

“Fake news threatens our confidence in the notions of one nation and the ability of public institutions to respond to societal needs. We do not need another law to address fake news. Instead, internet service providers and news organizations should observe their ethical obligations — that is, going beyond what they are compelled to do by law and instead do what they ‘should do.’

“Internet service providers must adopt a common set of ethical rules for news reporting on social media. They can be no different from the broadcast standards and practices of the television networks. When the internet site shows that it has adopted these minimum standards of journalistic integrity, we can have a minimum threshold of trust in that source. They should inform the public of the importance of recognizing that the content has been subjected to professional scrutiny. Since the service providers control the access to the social media consumer, the solution to the problem lies with them. Their failure to police what content can be posted on their sites encourages the creeping problem of fake news. It is time to act before a new generation of Americans is less informed and, therefore, equipped to govern.”

C. KERRY FIELDS

Professor of business law and ethics at the USC Marshall School of Business

Who bears the responsibility?

“People have always sought ideological comfort food. But for a long time we have had a distribution system based on large networks that limited the amount of media people could consume. That’s no longer the case. Facebook and other platforms bear enormous responsibility here. A supermarket doesn’t stock fake milk on its shelves, so the largest distributor of news shouldn’t be complicit in pushing erroneous information with no filter.

“I’ve dedicated my professional life to reporting accurately about difficult and complicated events, and I continue to believe there is a public value and an economic value to doing the job of a reporter as classically defined. We need a new type of civics education in high schools and elsewhere that teaches media literacy. There is simply no reason why this shouldn’t be a part of a high school curriculum. It has massive implications for our democracy.”

GABRIEL KAHN

Director of the Future of Journalism at the Annenberg Innovation Lab

All the clicks: A boon for social media, a bust for society

“The real answer is that we don’t know [the scale of disinformation] because Facebook is not an open platform that makes its data, people and algorithms available to researchers. We either have to make intelligent guesses, reverse-engineer their systems or trust the research that they publish on themselves. None of these options is satisfying.

“Facebook needs to be known as a place that can have influence on how people think and behave. If they didn’t, then why would advertisers give them money?

“Engagement is the holy grail for Facebook, but engagement is not what republics need in order to live together.”

MIKE ANANNY

Assistant professor of communication and journalism at USC Annenberg

Our morals determine what we believe

“There is a substantial literature in social psychology showing how people’s acceptance of factual claims is largely influenced by their moral opinions about those facts. This can help explain why we so readily accept fake news supporting our own political beliefs, while fake news supporting the other side has us immediately running to snopes.com to expose it as fake.”

JESSE GRAHAM

Assistant professor of psychology at the USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences

Nobody knows if you are a fake

“It turns out that much of the political content Americans see on social media every day is not produced by human users. These artificial intelligence systems can be rather simple or very sophisticated, but they share a common trait: They are set to automatically produce content following a specific political agenda determined by their controllers, who are nearly impossible to identify.

“The effectiveness of social bots depends on the reactions of actual people. We’ve learned, distressingly, that people are not able to ignore, or develop a sort of immunity toward, the bots’ presence and activity. Most human users can’t tell whether a tweet is posted by another real user or by a bot. We know this because bots are retweeted at the same rate as humans.

“Social media is acquiring increasing importance in shaping political beliefs and influencing people’s online and offline behavior. The research community will need to continue to explore ways to make these platforms as safe from abuse as possible.”

EMILIO FERRARA

Research assistant professor for the Information Sciences Institute at the USC Viterbi School of Engineering