Political polarization at its worst since the Civil War

Data scientists try to explain the U.S. government’s shifting ideologies over the past four decades

In recent years, members of the U.S. House and Senate have gained an almost infamous reputation for their ability to create partisan impasse. Stymied by issues like gun control, immigration and health care, they have been ineffective in brokering compromise, hampering the political process. Political polarization — one factor leading to this gridlock — has become very pronounced.

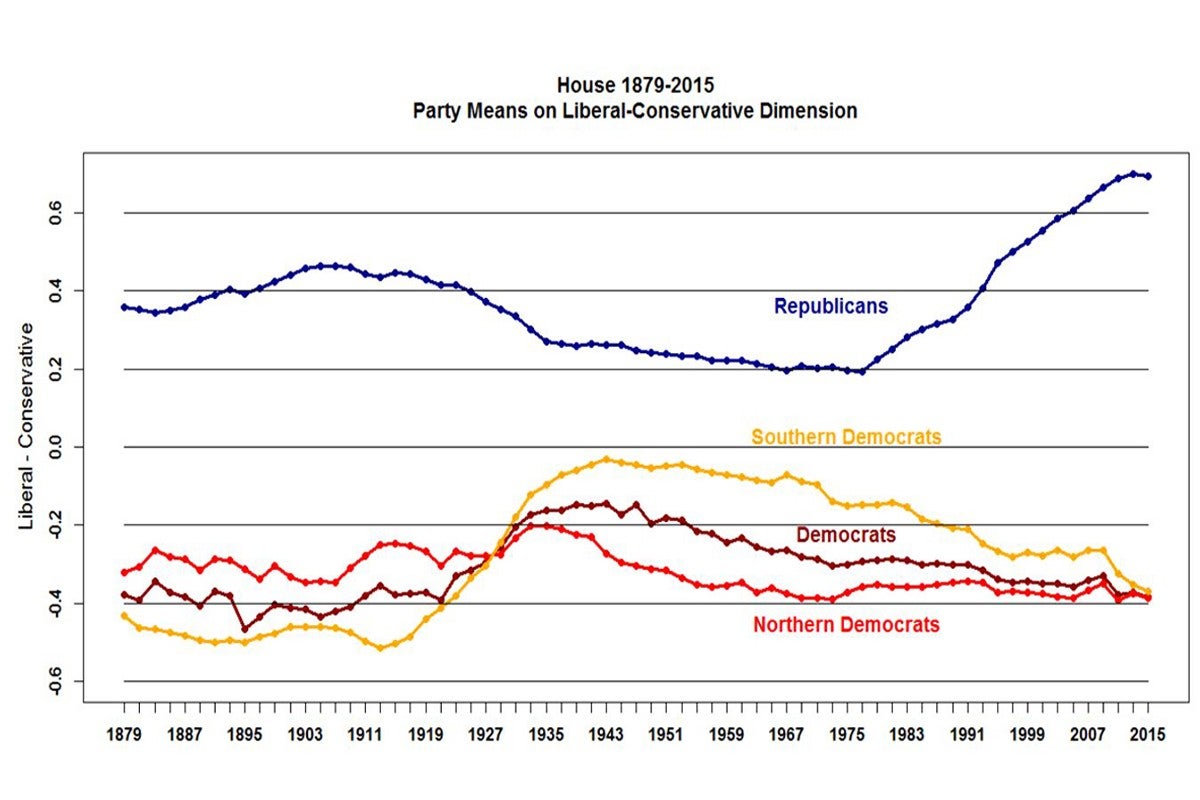

Following a period of a much more balanced Congress during the middle of the 20th century, ideological distance between the parties began to grow during the 1970s to the extent that Congress is now more polarized than at any time since the late 1870s Reconstruction Era.

James Lo, assistant professor of political science at the USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences, researches political preferences by analyzing voting records, survey data and cross-party affiliations. He measures levels of polarization between Democrats and Republicans over time through statistical analysis of congressional voting patterns.

His work helps generate Nominal Three-step Estimation (NOMINATE) scores — a multidimensional scaling method that political scientists Keith Poole of the University of Georgia and Howard Rosenthal of Princeton University developed to measure legislators’ liberal-conservative positions based on their roll call voting records.

According to Lo, ever-increasing levels of this kind of big data are available to researchers now that computation has become so much cheaper in recent years. Now there is a demand to bring these analytical techniques to new environments.

Political polarization has become one of the hottest research topics in political science today.

James Lo

“Political polarization has become one of the hottest research topics in political science today,” he said, “in large part because — both in the popular media and research — there is a lot of evidence suggesting that significant partisan impact occurs as a result of it.”

Left or right?

We typically think of legislators in Congress as lying on the left-right political spectrum, and according to traditional interpretation of the NOMINATE scores, Lo said, the left-right dimension alone accounts for about 85 percent of variance in all roll call voting. This means 85 percent of votes can be differentiated first and foremost on the basis of party affiliation.

Another way to think about polarization is to look at something called the overlap interval. This measure shows how many Republicans lie to the right of the most right-leaning Democrat and how many Democrats lie to the left of the most left-leaning Republicans. Today, the overlap interval is zero.

“This was certainly not always true,” Lo said. “In the 1960s, for instance, you had intervals where about 50 percent of the legislators in the two parties overlapped.”

Some political scientists have pointed out that — viewed within the context of data from the last two centuries — today’s levels of polarization are not such an alarming anomaly compared to those occurring during the time of slavery and similar points along the historical continuum. But this information can still tell us a lot about our current state of affairs.

The NOMINATE data has characterized today’s polarization in some interesting ways, namely that the Republican Party has experienced a dramatic shift to the right and ideological moderates in both parties have all but disappeared.

A huge gulf in the middle

Christian Grose, an associate professor of political science, has also done substantial research on analytics and election data.

“Because the NOMINATE data generated by James Lo and his co-authors shows that partisan elites in the U.S. are as polarized today as they were around the time of the Civil War, it suggests that there is a huge gulf in the middle that’s not being responded to by the two parties,” he said. “So it speaks to the question of how this polarization has inhibited the ability for the two-party system to function.”

So what could reduce the current state of polarization in Congress? Pressure from the electorate could potentially play a role, he said, so it is worth considering what kind of new political institutions could move the parties in a less polarized direction. The electorate could also encourage their parties to shift toward more centrist policies and ideologies, supporting more moderate candidates. Grose has done research showing that electoral reforms in California, for example, are associated with a reduction in polarization in legislatures.

Simply put, the challenge of political polarization is that it makes the political process very difficult to manage. Since Congress and the U.S. government were designed to include numerous checks and balances, compromise is essential in order for legislation to pass efficiently and effectively.

“In a political world where polarization grows more extreme over time, dealing with the political issues of the day becomes more and more difficult,” Lo said, “which is why this is an issue that’s so vexing and of so much concern and interest to political scientists.”